Category: Chapter 1

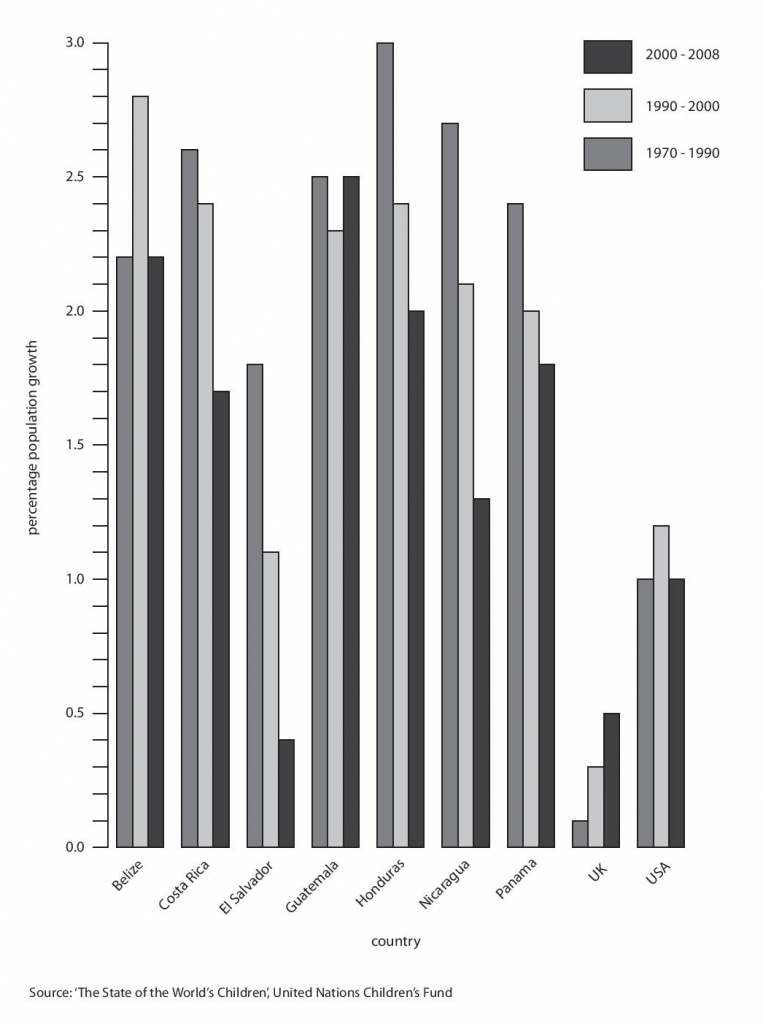

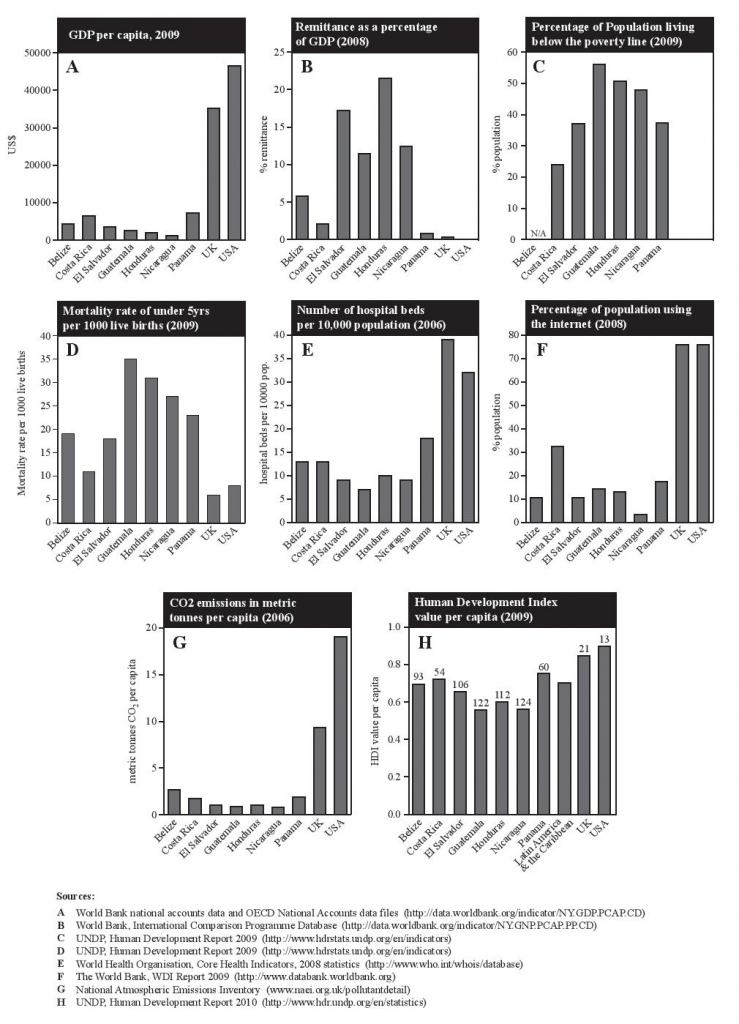

Selected indicators of development, Central America

Environmentalism, the water melon theory and the violence of development

If development is the primary theme of this book, a second and overlapping theme is that of the environment. All of the human indices briefly discussed in the previous section are also indices which relate to the environment in which humans live. We cannot divorce the two: human development and human environment. When we talk of the quality of the environment, some people refer solely to the natural environment; but the natural environment is also the social environment, the human environment. From my point of view these are the same; they are inter-twined and completely integrated.

If development is the primary theme of this book, a second and overlapping theme is that of the environment. All of the human indices briefly discussed in the previous section are also indices which relate to the environment in which humans live. We cannot divorce the two: human development and human environment. When we talk of the quality of the environment, some people refer solely to the natural environment; but the natural environment is also the social environment, the human environment. From my point of view these are the same; they are inter-twined and completely integrated.

Many indicators and examples which reflect the integration of these two issues are illustrated in the substantive chapters of the book. The indicators include measures which relate to pesticide residues, water quality, deforestation rates, biodiversity, CO2 emissions and similar, and these are given in the appropriate chapters rather than in this introductory chapter. Indicators such as these might normally be understood as measures of the quality of the natural environment, but it seems obvious to me that they are also integral parts of the social and human environment.

Despite this integration of the issues and the need to view developmental and environmental issues in a holistic light, there is still a widespread tendency to treat environmental problems as separate and apart from society. In the western capitalist world, environmentalists themselves are often ridiculed for their supposed divorce from realpolitik and characterised as tree-huggers and as successors to the hippy generation.

The view from right wing circles in Central America, however, is sometimes rather different where those who protest on environmental grounds are viewed as ‘water melons’ – that is, they are green on the outside and red on the inside, alluding to the colour of their politics. This is a hangover from the days when the enemy perceived by the established forces of society (that is oligarchic government and the military forces which protected the oligarchy) was communism. Those who protested during the insurgencies and wars of the second half of last century were simply deemed to be ‘communists’, a label that needed no further explanation to justify repression, violence and assassination. The use of the water melon label is intended to provide the same simple justification for repression against those who today protest against illegal logging, water pollution incidents, open cast mining, campesino displacements and the like. As we shall see in the following chapters, it is no exaggeration to say that the dark forces of the death squads and all they represent and protect are just as active now against the water melons as they were when the enemy was more easily identifiable as communists. If this sounds a little extreme, I refer the reader to several of the text boxes in Chapter 9, especially those headed ‘You couldn’t make it up’.

Such labels would be amusing if they were not seriously used by some of those who perpetrate the violence against a wide range of their fellow citizens, the environmentalists, social activists, trade unionists, journalists, community participants, and many others who seek social and environmental justice. As witnessed by the case studies, those who seek to defend their communities and their environment from damage are usually at the receiving end of the violence whilst those who pursue what are often called ‘development projects’ (especially on their websites) are those who practice violence in pursuit of the profits associated with the project.

The Environmental Network for Central America (ENCA)

ENCA is a small, UK-based NGO which serves as a discussion, information and news network for many local grassroots and community organisations in Central America and for a small number of supporters and interested parties within the UK. Although it is small, relatively powerless and financially poor, it supports the campaigns of numerous Central American organisations in their promotion of small-scale development projects and in their struggles against the imposition of development projects which they do not wish to have. For this reason ENCA prefers to refer to itself as a socio-environmental organisation rather than an environmental one.

ENCA is a small, UK-based NGO which serves as a discussion, information and news network for many local grassroots and community organisations in Central America and for a small number of supporters and interested parties within the UK. Although it is small, relatively powerless and financially poor, it supports the campaigns of numerous Central American organisations in their promotion of small-scale development projects and in their struggles against the imposition of development projects which they do not wish to have. For this reason ENCA prefers to refer to itself as a socio-environmental organisation rather than an environmental one.

Many of the projects and campaigns which it supports or has supported are detailed in the following chapters. In Chapter 6, for example, the campaigns of the Environmental Movement of Olancho (MAO by its Spanish initials) in favour of a prohibition on logging in certain areas of the department of Olancho and against the companies which participate in illegal logging are detailed and discussed. ENCA has supported the MAO in these campaigns in a number of ways.

Over the 24 years of its existence, the thrice yearly ENCA Newsletter has consistently covered issues of food production, pesticide use and contamination, food security, access to water and sanitation, the problems of energy production and distribution, resource extraction, deforestation and many others. It has particularly focused its attention on small-scale and grassroots solutions to many of these problems. It has also found it essential to focus much attention on the violence against persons who have been defending their community and their environment against destruction by so-called development projects.

As editor of the ENCA Newsletter, I have been constantly faced with decisions about whether to include news of the assassinations of Central American environmentalists and social activists. No issues of the newsletter have passed by without the need to make such a decision, and so many killings and death threats have had to go unremarked in our brief twelve page editions due to the weight of importance of issues such as those listed above. During the course of my editorship, it became clear to me that the violence directed at anybody who spoke out against the specific and general thrusts of neoliberal economic development model was related to these issues. It has become impossible for me to study the issues of environment and development in Central America without placing the assassinations, threats, evictions, dispossessions, other forms of violence and human rights abuses at the centre of the analysis. Equally, it has become impossible not to see the links between the violence, the perpetrators of the violence and those whose interests they represent – the oligarchies of each of the Central American countries, the transnational corporations (TNCs), the powerful western technocratic nations and the international financial institutions (IFIs). These are the organisations and people who hold the reins of power and who impose the top-down model of development on Central American populations, and it is they who bear the responsibility for the violence which is associated with this ‘development’.

Articles in the ENCA Newsletter have been an important stimulus for the book. The range of issues covered by the newsletters is broad and rarely can its articles do more than scratch the surface of any given issue. This book and website are intended to delve deeper into the given issues which form the focus for each chapter.

Global pressures on Central America

Whilst Central America is the stage for the case studies and examples, the theme of development is a general one which applies to other regions of the world too. Since President Truman introduced the race for development in 1949, western style development has been inextricably linked with the need for economic growth. Even now, when the predominant system of development is facing financial meltdown and the planet is facing environmental catastrophe, a majority of scholars exercise their minds in the attempt to find the most appropriate way of achieving a form of economic growth that will reduce human poverty and inequality and ensure development for all. These scholars and practitioners of development include Fukuyama, De Soto, Sachs, Sen, Easterly, Collier, and Moyo. Various thinkers of renown and critics of neoliberalism, such as Stiglitz, Shiva, Klein and Khor, have questioned this emphasis and see the pursuit of ever greater economic growth as the villain of the piece. They have had some success in academia, the liberal media and with the anti-globalisation movement, but little effect in practical and political terms on a global scale and in terms of making progress in preventing the major environmental threats facing the planet.

The development of Central America has exercised the minds of many other non-Central Americans over the last few decades, not least employees of the World Bank, IMF, various US agencies such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), and the European Union. US agencies such as these take it as standard operating procedure that they should interfere in Central American elections and fund Central American political parties which support US positions. This is often done in contravention of international law and is always done against the spirit of free and fair elections. This distortion of the idea of democracy offers us a perverted view of development, and is yet another illustration of how development is dictated by a western, specifically US, agenda, imposed as a top-down model of development, violently if necessary.

The prevailing model of development today is that of neoliberalism or neoliberal economic development. It has been so since Ronald Reagan outlined its essence in his ‘magic of the market’ speech at the 1981 North-South Conference in Mexico. There, neoliberalism was characterised by the dominance and application of free market principles and trickle-down growth. Neoliberalism sees development as a single linear progression of economic growth and wellbeing, often portrayed as a series of steps or stages (such as Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth[i]) to the promised land of a developed state. There is an almost universal acceptance that there can be no ‘development’ without economic growth and no economic growth without free trade, an equation that commands near universal respect but which Gilbert Rist warns us we should question.[ii] Given that neoliberalism is the prevailing model of development, it is impossible not to associate it with the violence which characterises so many of the ‘development’ projects which are witnessed in the following chapters of this book.

Many more have joined the debate about ‘development’ since the Thatcher-Reagan axis took the direction of development along the neoliberal lines of the Washington Consensus[iii], a direction which, at a macro scale, is still largely followed today despite the recent financial crisis that it has suffered. Indeed, it is interesting to note that the IMF (which must be held at least partly responsible for leading the world into the financial crisis) has been put in charge by the G8 leaders of recovering from it, an appointment that does not bode well for the acceptance of progressive ideas and experimentation with alternatives.

It is of interest to note the results of the socialist and social democratic governments that have arisen over the last ten to fifteen years in Latin America. Before the 1980s, such movements would have been undermined, subverted and put down by the violent hegemony of national oligarchies supported by the United States. These days such tactics are much less likely to be employed, but they are still far from dead and buried as was shown by the coup d’état in Honduras in 2009 (see Chapter 9). Rather, the new left and centre-left governments have been allowed to follow their own chosen route of development with the western powers feeling relatively safe in their belief that there is only one route available and that is the route dictated by the IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organisation (WTO), namely the Washington Consensus.

There is no doubt, however, that neoliberal economic development has come to be reviled by large sectors of the population since the onset and continuation of the 2008 financial crisis. As Seumas Milne puts it:

A voracious model of capitalism forced down the throats of most of the world for the last 20 years as the only acceptable form of economic management, at a cost of ever-widening inequality and devastating environmental degradation, has now been discredited.[iv]

Milne refers to “the tide of progressive social change that has swept Latin America” as a “globally significant shift”.[v] I should like to agree that we are on the cusp of a major global shift away from the single, prevailing, imposed model of neoliberalism, but I believe that such a judgement may be a little premature. An indication of the limited options available to the recently elected and relatively progressive Third World governments is the growing rift that is forming between the social movements which have supported those new and progressive governments and the new governments themselves. This rift was shown at the Americas Social Forum held in Paraguay in August 2010. In many of the sessions the social movements condemned the progressive governments on the grounds they were continuing with an economic model based on extractive industries such as opencast mining and the monoculture of genetically modified crops like soya and sugar cane for fuel. The debates focused on the ‘commons’, such as water and biodiversity, which continue to be appropriated by multinationals, undermining the food sovereignty of the people.[vi]

Whilst the grassroots clamour for alternative development routes is still growing, there is limited evidence that governments are responding accordingly. But despite this continuity of neoliberal economic development, even those who retain their faith in neoliberal economics now recognise that it has failed to produce the development of humanity in a good number of countries – witness Collier’s book ‘The Bottom Billion’, and Moyo’s ‘Dead Aid’. As Eduardo Galeano states, “Despite its deceptive splendours, this development is a banquet to which few are invited and whose main dishes are reserved for foreign stomachs.”[vii]

[i] Rostow, W. (1960) The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-communist Manifesto, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[ii] Op.cit. (Rist, 2008).

[iii] The Washington Consensus – a set of economic principles that emerged from the US government, IMF and World Bank as an international geopolitical regime.

[iv] Seumas Milne (30 December 2009) ‘A decade of global crimes, but also crucial advances’, The Guardian, London.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] The Guardian (17 August 2010) ‘New rifts in Latin America, but no confrontation’, The Guardian, London, www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/aug/17/social-rift-latin-america

[vii] Eduardo Galeano (1973) Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, London: Monthly Review Press.

Time scale

In this book and website, I try to show how the last three decades of development-dominated international politics has manifested itself on the ground in the region of Central America.

In this book and website, I try to show how the last three decades of development-dominated international politics has manifested itself on the ground in the region of Central America.

The time scale covered by the case studies examined in the book extends back to the late 1980s when the region began to emerge from its wars and the approaching finale of the global Cold War began to usher in a period of western-led development. For Central America, this meant the start of a period of neoliberal economic development in which state assets and services were to be privatised, liberalised and deregulated, and Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs) were imposed on the national governments by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The period also coincides with a growing global environmental awareness that manifested itself in the 1992 Rio Conference, other UN-organised mega-conferences, the UNDP’s Human Development Reports and international development targets.

Although development in Central America before and during the Cold War is covered in other works (for example, Victor Bulmer-Thomas, Bill Weinberg, Duncan Green and Jenny Pearce – see the Bibliography), I reserve the right to search a little further back in history for explanations relating to a few case studies which cannot be understood without reference to events that took place before this latest period of the late 1980s onwards.

Structure of the book and associated website

The major themes of development, environment and globalising capitalism run through each chapter. In the choice of subjects or activities for study I have tried to select those that relate to basic human needs – hence, chapters on the food crisis, the water crisis and the energy crisis – those that cover the major economic activities of the region – hence, chapters on mining, forestry, industrialisation and free trade – and those that deal with issues of great social concern – hence, chapters on indigenous groups and violence and human rights abuses. The last substantive chapter (covered only in the website), Chapter 10, deals with global issues which directly affect the region of Central America.

After outlining the major thrusts of development in each chapter, consideration is given to the significance of the development of alternative modes of production.

A note about the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

In 2000, world leaders developed the Millennium Development Goals – eight targets intended to eradicate global poverty and human suffering by 2015. See Tables 1.1 for a summary listing of the targets and Table 1.2 for more detail.

Because of word limit for ‘The Violence of Development’ book, discussion of the MDGs was omitted from Chapter 1. In-depth comment is also reserved for 2015, the MDG target year.

Paul Oquist, Nicaraguan presidential advisor, has noted that the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has claimed that Nicaragua will achieve the UN MDGs, including reductions in poverty and malnutrition by 2015. CEICOM (Centre for Research into Investment and Business, El Salvador), on the other hand, estimated that the global economic crisis of 2008 added 39 million new people to the tally of those living in poverty in Latin America, giving a total of 189 million out of a grand total of 550 million Latin American population (34%)[i]. It is highly unlikely that Central America will have escaped this effect of the global financial crisis.

There have been varying reports about progress made towards the MDGs by Central America nations, and the official (?) verdicts are awaited in the target year 2015

[i] Figures from the United Nations’ Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

The UN’s Millenium Development Goals – summary

GOAL 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

GOAL 2: Achieve universal primary education

GOAL 3: Promote gender equality and empower women

GOAL 4: Reduce child mortality

GOAL 5: Improve maternal health

GOAL 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

GOAL 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

GOAL 8: Develop a global partnership for development

The UN’s Millenium Development Goals – in full

GOAL 1 – Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

Target 1: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than one dollar a day

Target 2: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

GOAL 2 – Achieve universal primary education

Target 3: Ensure that, by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling

GOAL 3 – Promote gender equality and empower women

Target 4: Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and to all levels of education no later than 2015

GOAL 4 – Reduce child mortality

Target 5: Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate

GOAL 5 – Improve maternal health

Target 6: Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio

GOAL 6 – Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

Target 7: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS

Target 8: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases

GOAL 7 – Ensure environmental sustainability

Target 9: Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmes and reverse the loss of environmental resources

Target 10: Halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water

Target 11: By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers

GOAL 8 – Develop a global partnership for development

Target 12: Develop further an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system

Target 13: Address the special needs of the least developed countries

Target 14: Address the special needs of landlocked countries and small island developing states

Target 15: Deal comprehensively with the debt problems of developing countries through national and international measures in order to make debt sustainable in the long term

Target 16: In cooperation with the developing countries, develop and implement strategies for decent and productive work for youth

Target 17: In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable, essential drugs in developing countries

Target 18: In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications