By Rita Jill Clark-Gollub (Washington), Erika Takeo (Managua), and Avery Raimondo (Los Angeles)

Published originally at the Council of Hemispheric Affairs (COHA):

We are grateful to COHA, to Fred Mills Co-Director of COHA and to the three authors for permission to reproduce the article on ‘The Violence of Development’ website.

Lucila Reyes of the Marlon Alvarado community, in Santa Teresa, Carazo where women play an active role in the construction of food sovereignty through peasant organisations and government programmes. Shown with tomatoes grown in her agroecological garden. Photo-credit: Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo (Rural Workers Association or ATC)]

Key words: La Vía Campesina; agribusiness; food security; food sovereignty; Nicaragua; Hambre Cero; agro-ecology.

“A nation that cannot feed itself is not free.”

Fausto Torrez, Nicaraguan Rural Workers Association

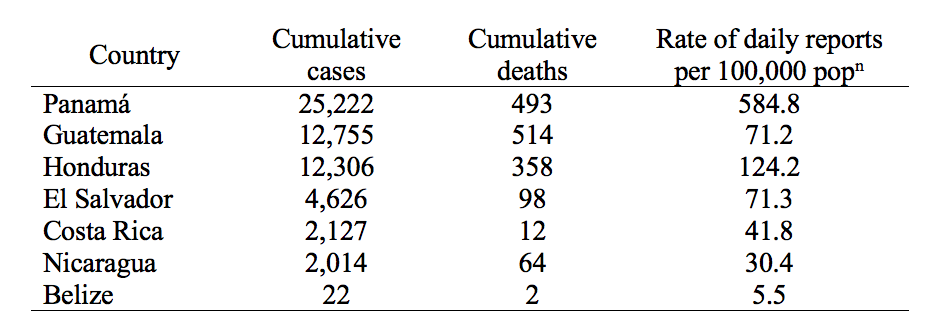

An array of UN agencies is predicting a global hunger pandemic triggered by COVID-19 lockdowns, with the head of the World Food Programme stating that there is “a real danger that more people could potentially die from the economic impact of COVID-19 than from the virus itself.”[1] At least 10 million more Latin Americans are expected to join the 3.4 million who were already experiencing chronic food insecurity.[2] These devastating effects will be long-term, as each percentage point drop in global GDP is expected to cause 0.7 million more children to be stunted from undernutrition.[3] There are clear signs that the food shortages have already arrived, as flags indicating hunger are spotted outside homes from Colombia to the Northern Triangle of Central America,[4] while violently repressed hunger protests have occurred in places such as Honduras[5] and Chile.[6] As a street vendor in El Salvador put it, “If the virus doesn’t kill us, hunger will.”[7]

But in the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, there are no hunger flags flying. The market stalls are stocked, customers are buying, and prices are stable. Nicaraguan small farmers produce almost all the food the nation consumes, and have some left over for export. We will examine how this is possible.

At the June 9, 2020 launching of his Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition,[8] UN Secretary-General António Guterres not only called for urgent action to address this hunger crisis, but also to take the opportunity to shift towards more sustainable food systems. This transition is something that the world’s peasants have been calling for since they founded La Vía Campesina (LVC) in 1993. It is now urgent to listen to what over 200 million peasants, women farmers, indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples, fisherfolk, and pastoralists have been saying about our food systems:

“The pandemic has highlighted yet another ill of countries becoming too dependent on large international food industries [and their international supply chains]. For decades, governments did little to protect small farms and food producers which were pushed out of business by these growing dysfunctional corporate giants. … They stood idle as their countries grew increasingly dependent on a few major suppliers of food who forced local producers to sell their produce at unfairly low prices so corporate executives can keep growing their profit margins.”[9]

Agribusiness is also exacerbating the world’s most pressing problems: its Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) crowd immune-stressed animals, making them susceptible to viruses that can cross over to humans;[10] its fossil fuel- and chemical-intensive practices account for at least a third of the greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change;[11] and its genetically modified seeds are known to diminish biodiversity. Moreover, in Latin American commercial food systems, it is fueling price increases during the pandemic.[12]

La Vía Campesina’s answer is food sovereignty, which is defined as “the right of people to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”[13] It prioritizes: 1. local agricultural production in order to feed the people; and 2. peasants’ and landless people’s access to land, water, seeds, and credit. This approach actually works in combating hunger, as peasants and smallholders produce 70-75 percent of the world’s food on less than one quarter of the world’s farmland.[14] When peasant movements partner with progressive governments, the results can be astounding, as in the case of Nicaragua.

The peasant movement in Nicaragua

The Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo (Rural Workers Association or ATC) was founded during the war to overthrow the U.S.-backed Somoza dictatorship, one year before the 1979 victory of the Sandinista People’s Revolution. It brought together peasants, both small farmers wanting to procure their own land as well as farm workers organising for union rights. The ATC has continued to represent these groups of workers throughout its 42-year history and was one of the national organisations that founded La Vía Campesina in 1993.[15]

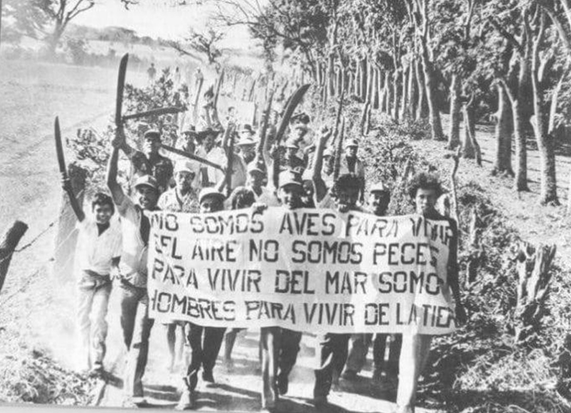

Peasant march in 1980s. “We are not birds who live in the air; we are not fish who live in the sea; We are Men who live off the land.”

In the 1980s, the Nicaraguan revolutionary government launched a massive land reform programme, which distributed about half the country’s arable land (5 million acres) to 120,000 peasant families. Several other peasant groups formed during that first decade of the revolution as the cooperative farming movement prospered, even coming to include the families of former contra fighters, who had been adversaries of the Sandinista government. Later, during the neoliberal administrations of 1990-2006, these groups worked to defend the gains of the revolution, sometimes including worker occupations of state farms to prevent them from being privatized. By 2006, and inspired by the 1987 Constitution that guarantees protection against hunger,[16] some 73 Nicaraguan organisations belonged to the Interest Group for Food and Nutritional Sovereignty and Security (GISSAN) that was advocating for a Food Sovereignty Law. Several of them helped the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) get elected back into office at the end of that year.[17]

Food Sovereignty since 2007

In the current stage of Sandinista governance that started in 2007, the strategy to increase food sovereignty by providing land has continued. Almost 140,000 land titles (some from land distributed during the 1980s land reform) were issued to small producers from 2007 to 2019. Women have particularly benefited from receiving proper titles to their land (55 percent) and 304 indigenous and Afro-descendant communities on the Caribbean coast have received collective titles. The titled area amounts to 37,842 km2, or 31.16 percent of the national territory.[18]

Social programmes that help small farmers feed themselves and their communities have imbued life in the countryside with dignity while reducing hunger. These initiatives are inspired by Augusto C. Sandino’s vision of an economy based on land-owning peasants and indigenous peoples farming in organised cooperatives—a core component of the FSLN’s Historic Programme. Law 693 on Food and Nutritional Sovereignty and Security, enacted in 2009, was one of the first in Latin America to recognize the concept of food sovereignty and actually build it with government support.[19] The commitment of the FSLN government to food sovereignty has led to dozens of programmes to improve the livelihoods and autonomy of small farmers while strengthening local food systems.

The signature initiative is the Hambre Cero (Zero Hunger) programme which began in 2007 and provides pigs, cows, chickens, plants, seeds, and building materials to women in rural areas to diversify their production, improve the family diet, and strengthen women-led household economies.[20] By 2016, the programme had benefited 150,000 families or 1 million people, increasing both their food security and the nation’s food sovereignty.[21]

Some 150,000 families in the Zero Hunger programme have received farm animals and farming inputs (photo-credit: Susan Meiselas, Fundación Entre Mujeres).

Interviews completed as part of a solidarity testimonies project[22] with ATC members in the Marlon Alvarado community, many of whom are also beneficiaries of government programmes, illustrate the impact of Hambre Cero. For example, one woman said:

“I have always been in social movements, since I was young. We are a group of women working here. We are united and in solidarity, all of us. …The ATC has taught us about women’s entrepreneurship… The government is encouraging us to always cultivate our land, so that we have our food. They give us citrus, they give us bananas, papaya, lemons. We just have to go harvest. We have jocote, mango. They always continue the [Hambre Cero] programme so that we grow something. In our plot, we are always growing something.”

Another woman in the same community said: “I have two male pigs, boars, for breeding: if someone else has a sow, they bring it to the boar and I get a piglet in return. For every sow they bring to the boar, I get a little pig. Or if someone says to me, ‘I have all the piglets sold; I’ll give you the money. What do you say?’ ‘Okay,’ I say. We agree.”

Additionally, the Ministry of the Family, Community, and Cooperative Economy (MEFCCA) and municipal governments organise farmers markets to improve peasant incomes while making nutritious, locally-grown food accessible to consumers, that is produced without chemical fertilizers or pesticides. The Nicaraguan Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA) works to improve and maintain the country’s genetic material by organising community seed banks,[23] and the National Technological Institute (INATEC) provides free technical degrees in agriculture, livestock care, value-added processing, and beekeeping, to name a few.[24] A new programme called NicaVida will reach 30,000 rural families with tools, fencing, water tanks, chickens, and other materials to improve family diets and household economies in the Dry Corridor[25] areas which are particularly impacted by climate change.[26]

Emerita Vega of the Marlon Alvarado community in Santa Teresa Carazo, coordinator of the ATC women’s group, in her pineapple parcel. Pineapples provided by a government farm diversification programme through INTA (photo-credit: “Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo”, Rural Workers Association, or ATC).

The breadth and territorial reach of these programmes keep Nicaragua’s peasants and small farmers free from dependence on global markets; their diversified production is organised to feed their families and local communities, with increasing access to seeds, water, and credit, thereby creating the conditions to achieve food sovereignty.

A poverty and hunger fighting programme targeting urban residents is Zero Usury, which is part of the national food ecosystem since it serves many who work in open-air markets. This programme, administered by the MEFFCA, gives low interest loans and grants to small business owners (primarily women) and offers free entrepreneurship training, funded in part by Venezuela and other ALBA countries. Over 800,000 women have benefited from the programme since 2007, which has been crucial to the success of the popular economy (self-employed workers, small farmers, family businesses, and cooperatives) which accounts for over 70 percent of employment.

Long-time activist and current presidential advisor Orlando Núñez explains the philosophy behind these programmes and why they work: “The heart of the Hambre Cero programme is giving capital to peasant families. A cow is capital because she reproduces; sows, seeds, and hens reproduce. The first message is not to treat people like poor people; they are only poor because they have been impoverished. … Offering poor people a glass of milk or a slice of bread is an act of charity, not revolution. … The revolutionary thing about Hambre Cero in Nicaragua is that it treats people like economic actors. …That is the most revolutionary message of the Sandinista revolution.”[27]

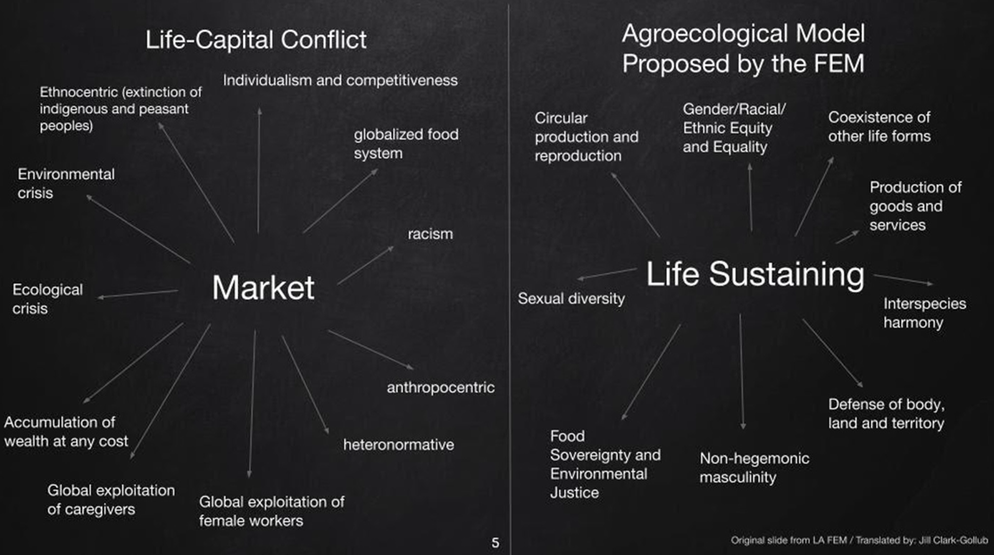

The initiatives for this second phase of the Sandinista Revolution are all complemented by the grassroots work of social movements. The ATC and LVC have established a campus of the Latin American Institute of Agroecology (IALA) in Nicaragua for youth from Nicaragua and throughout the Mesoamerican and Caribbean region. The school not only imparts technical training on agro ecological production of crops and animals, but also political and ideological education so that students come to understand today’s clash between two models of agriculture: one (the agribusiness model) in which food is a business for the benefit of corporations, and another (the food sovereignty model) in which food is a human right for all. The programme encourages peasants to be each other’s teachers and have agency over their own lives, reclaiming their peasant identity and culture. It is an education that focuses on staying in the countryside and producing food that stays within the local market.

Throughout the country the ATC and other peasant organisations have been organising local workshops to train agroecological promoters, support women’s cooperatives in marketing their farm products, formalize peasants’ land titles, and prepare on-farm biofertilizers and composts. All of this supports the construction of food sovereignty.

Students at La Vía Campesina’s Latin American Institute of Agroecology campus in Santo Tomás, Chontales (photo-credit: Latin American Institute of Agroecology “Ixim Ulew”).

ATC youth make biofertilizer in an agroecology workshop, in Santa Emilia, Matagalpa, 2015 (photo-credit: “Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo”, Rural Workers Association, or ATC).

Hunger outcomes in Nicaragua and Central America

All indications are that these programmes have resulted in a better fed population in Nicaragua. In its 2019-2023 Strategic Plan for Nicaragua, the United Nations World Food Programme said that “In the last decade… Nicaragua is one of the countries that has reduced hunger the most in the region,”[28] while the government reports that chronic child malnutrition dropped from 21.7 percent in 2006 to 11.1 percent in 2019 for children under 5 years of age.[29] Nicaragua was also one of the first countries to achieve Millennium Development Goal Number 1 of cutting undernutrition in half from 2.3 million in 1990-1992 to 1 million in 2014-2016, placing it among the countries of the region that had reduced hunger the most in the previous 25 years. Vitamin A deficiency among children under 5 was also eliminated.[30]

Nicaragua’s advances are reflected in the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Hunger Map.[31] Unfortunately, that map shows that neighboring Honduras and El Salvador did not achieve the Millennium Development Goal on hunger reduction, and that Guatemala did not even make progress. This stagnancy may be related to the fact that US exports to the Northern Triangle countries increased substantially since the signing of the Dominican Republic-Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). These three countries imported about US$5.9 billion of agriculture products from the world in 2016, including beans and dairy products from Nicaragua, and corn, soybean meal, wheat, poultry, rice, and prepared foods from the US. Imports of many of these US foods increased by 100 percent or more from 2006-2016, coming to comprise about 40 percent of all food imports for these countries.[32] Unfortunately, food prices in these countries are on the rise precisely when people have less income with which to purchase food due to COVID-19 lockdowns at home and in the US, from which Central American countries receive remittances. Parts of Guatemala are already receiving half the remittances they received at this time last year.[33] Even Nicaragua’s wealthier neighbor to the south, Costa Rica, has become dependent on imported beans, rice, beef, and corn after opening the market through free trade agreements. At a recent LVC regional meeting, a Costa Rican peasant leader discussed how vulnerable the country has become, saying “COVID is stripping us bare.” Not only are grain prices rising while vegetable crops rot because they cannot reach consumers, unemployment is expected to double from 12.5 percent to 25 percent,[34] and 57 percent of Costa Ricans report having trouble making ends meet.[35] This brings major worries of increased hunger.

Food sovereignty and the pandemic in Nicaragua

Ninety percent of the food consumed in Nicaragua is produced within the national borders, 80 percent of it by peasants.[36] This includes all of the beans, corn, fruits, vegetables, honey, and dairy products, while there is sufficient surplus of beans and dairy to export. Nicaragua’s food self-sufficiency is growing precisely while other developing countries are increasingly becoming agro-exporters of a few crops (e.g. pineapples or bananas) while ever more dependent on imports to feed their populations. Rice is the only component of the basic diet that is not completely homegrown, but domestic rice production has increased from meeting 45 percent of the country’s demand in 2007 to 75 percent of demand today. The government is working with producers to bring it up to 100 percent within 5 years. Nicaragua is indeed very close to achieving food sovereignty, the true anti-hunger model, which bodes well for times of crisis such as now with the economic impacts of the pandemic and the interruption of food distribution supply chains in other countries.

In the context of the pandemic, both the government and social movement organisations are determined to take food sovereignty to the next level. For example, the government just launched a National Plan for Production focused on increasing production of basic grains to cover all internal food needs, and also guarantee the production of crops for export.[37] Food stocks are normal, prices are stable, production has continued normally since there has not been a work lockdown and most food is produced in small family units, and the rains have started for what looks to be a good planting season. Meanwhile, the Nicaraguan member organisations of LVC are launching the Agroecological Corridor, a process of territorializing agroecology based on peasant-to-peasant exchanges as a response to the threats being posed by climate change.[38] Because training of youth also must continue, coursework at LVC’s flagship Latin American Institute of Agroecology is taking place online[39] while the institute’s campus is implementing a full food production plan that includes grains, root vegetables, and animals. LVC has also launched the emergency campaign “Return to the Countryside”[40] to be adopted not just in Nicaragua, but internationally.

Traditional field work by a pair of oxen in a (non-GMO) corn field in the northern department of Madriz (photo-credit: Friends of the ATC).

Other challenges to Nicaragua during the pandemic

COHA has previously reported on the Nicaraguan government’s robust response to COVID-19 within the health sphere, amidst a vigorous disinformation campaign waged against the population and government in what clearly appears to be a regime change operation funded by the US.[41] That regime change effort is no doubt partially inspired by Nicaragua’s food sovereignty policy, which threatens the dominance of US corporate agribusiness around the globe. For example, USAID has flooded food systems with Monsanto (now Bayer) GMO seeds in countries ranging from India[42] to Iraq[43] to several countries of Africa[44] and Latin America.[45] This approach could be undermined if more developing countries decide to produce their own food through agroecological practices.

USAID was one of the agencies funding opposition groups involved in a violent attempted coup in Nicaragua in 2018, as is well-documented in Live from Nicaragua: Uprising or Coup?[46] It is not surprising, then, that the representative of Cargill in Nicaragua and head of the U.S.-Nicaragua Chamber of Commerce was one of the leaders of the opposition during the attempted coup.[47] While Nicaragua does not have the oil and minerals that draw international attention to Venezuela and Bolivia, agribusiness is a hugely profitable industry and the Nicaraguan peasants are setting a powerful example by rejecting it and feeding their people to boot.

Fighting a disinformation campaign while the country faces the same pandemic that has overwhelmed much wealthier countries will certainly be challenging for Nicaragua, particularly since unilateral coercive measures illegally imposed by the US block access to aid funds. But at least her people have the comfort of knowing that there will be no death caused by hunger. In fact the food system recently withstood a formidable test during the 2018 coup attempt, when violent roadblocks held all the main roads and highways captive. Thanks to local food production and distribution systems, and clever determination to circumvent the roadblocks, people using the popular economy were still able to get food and at relatively stable prices, even when the Walmart-owned supermarket chains had empty shelves.

In an interview in late April, the leader of a peasant women’s organisation was asked about Nicaragua’s handling of the coronavirus. Her concern was not as much about catching the virus as that, “We will have food. It’s true that it is going to be hard; we will probably have a recession. But the important thing is that we have all the basic foodstuffs. We Nicaraguans are not quite 100 percent food self-sufficient. But we [in the Fundación Entre Mujeres] will do everything within our power to be as self-sufficient as we can so that the government does not need to give us aid and can give it to people who have greater needs than we have. We are taking a stance of dignity, being part of the solution.”[48]

That attitude, coupled with a commitment to agroecology and food sovereignty, is what has Monsanto/Bayer, Cargill, and their guardians at USAID worried.

This graphic by the Fundación Entre Mujeres (FEM) of northern Nicaragua shows the difference between market-based food systems and agroecology-based ones.

Rita Jill Clark-Gollub is a COHA Assistant Editor/Translator, based in Washington, DC

Erika Takeo is a member of the International Relations Secretariat of the Rural Workers Association (ATC) and Coordinator of the Friends of the ATC solidarity network and is based in Nicaragua

Avery Raimondo, from Friends of the ATC solidarity network, is based in Los Angeles, California

The following guest editors commented on this text:

Christina Schiavoni is an independent food sovereignty researcher and activist.

Magda Lanuza, a Nicaraguan who lives in El Salvador, holds a Master’s in International Sustainable Development from Brandeis University and has several years of experience working on social development and environmental protection in Central America.

End notes

[1] “World food agency chief: World could see famines of ‘biblical proportions’ within months,” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-famines-united-nations-warning/

[2] “Latin America and Caribbean: Millions more could miss meals due to COVID-19 pandemic,” https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/05/1065032

[3] “2020 Global Nutrition Report,” https://globalnutritionreport.org/

[4] “La contraseña de hambre en Latinoamérica: colgar un trapo rojo,” https://www.lavozdeasturias.es/noticia/actualidad/2020/04/27/contrasena-hambre-colgar-trapo-rojo/0003_202004G27P17991.htm and

[5] “Reprimen manifestantes que exigían comida en medio de crisis por coronavirus,” https://notibomba.com/honduras-reprimen-manifestantes-que-exigian-comida-en-medio-de-crisis-por-coronavirus/

[6] “Coronavirus: Chile protesters clash with police over lockdown,” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-52717402

[7] “En Guatemala y El Salvador piden comida con banderas blancas,” https://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/mundo/2020/05/21/en-guatemala-y-el-salvador-piden-comida-con-banderas-blancas-1720.html

[8] “Policy Brief: The impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition,” https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_policy_brief_on_covid_impact_on_food_security.pdf

[9] “The Solution to Food Insecurity is Food Sovereignty,”

https://viacampesina.org/en/the-solution-to-food-insecurity-is-food-sovereignty/

[10] “Factory farms: A pandemic in the making,” https://uspirg.org/blogs/blog/usp/factory-farms-pandemic-making

[11] “Agriculture is one of the biggest contributors to climate change. But it can also be part of the solution. https://investigatemidwest.org/2019/09/27/agriculture-is-one-of-the-biggest-contributors-to-climate-change-but-it-can-also-be-a-part-of-the-solution/ and “Lessons from the Green Revolution,” https://nature.berkeley.edu/srr/Alliance/lessons_from_the_green_revolutio.htm

[12] “Costlier Food Hits Latin America’s Poor and Adds to Unrest Risk,” https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-08/costlier-food-hits-latin-america-s-poor-and-adds-to-unrest-risk

[13] La Vía Campesina, 2008, Food Sovereignty for Africa: A challenge at our fingertips, <http://viacampesina.net/downloads/PDF/Brochura_em_INGLES.pdf> p.2

[14] “Hungry for land: small farmers feed the world with less than a quarter of all farmland,” https://www.grain.org/article/entries/4929-hungry-for-land-small-farmers-feed-the-world-with-less-than-a-quarter-of-all-farmland

[15] Website: Friends of the ATC, History, https://friendsatc.org/history/

[16]https://nicaragua.justia.com/nacionales/constitucion-politica-de-nicaragua/titulo-iv/capitulo-iii/#:~:text=Es%20derecho%20de%20los%on on20nicarag%C3%BCenses,Art%C3%ADculo%2064.

[17] Araujo and Godek, “Opportunities and Challenges for Food Sovereignty Policies in Latin America: The Case of Nicaragua,” in Rethinking Food Systems – Structural Challenges, New Strategies and the Law, (New York: Springer, 2014), 51-72.

[18] “Nicaragua’s human rights achievements over the last 10 years,” http://www.tortillaconsal.com/tortilla/node/6571

[19] Araujo and Godek.

[20]CELAC website, Food and Nutrition Security Platform, https://plataformacelac.org/en/pais/nic

[21] “Revolución Sandinista restituye derechos a mujeres y los campesinos,” http://www.tortillaconsal.com/tortilla/node/7702

[22]“Testimonies,” https://friendsatc.org/about/resources/testimonies/

[23] McCune, Nils (2016): “Family, territory, nation: post-neoliberal on agroecological scaling in Nicaragua,” available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314022520_Family_territory_nation_post-neoliberal_agroecological_scaling_in_Nicaragua

[24] INATEC website: https://www.tecnacional.edu.ni/educacion-tecnica/

[25] “How the Climate Crisis is Driving Central American Migration,” https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/how-climate-crisis-driving-central-american-migration#:~:text=The%20Dry%20Corridor%20is%20an,%2C%20Costa%20Rica%2C%20and%20Panama.&text=It%20has%20to%20do%20with,circulation%20patterns%20near%20Central%20America.

[26] “Nicaraguan Dry Corridor Rural Family Sustainable Development Project,” https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/project/id/2000001242

[27] “Revolución Sandinista restituye derechos a mujeres y los campesinos,” http://www.tortillaconsal.com/tortilla/node/7702

[28] “Draft Nicaragua country strategic plan (2019-2023),” https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000100987/download/

[29] “To the people of Nicaragua and to the world, COVID-19 report, a singular strategy,” page 32, http://www.tortillaconsal.com/white_book_sars-cov-2_26-5-2020.pdf

[30] “Nicaragua Interim Country Strategic Plan,” https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000020983/download/

[31] “FAO Hunger Map 2015,” http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4674e.pdf

[32] “US Agricultural Exports to Central America’s Northern Triangle Prosper Under CAFTA-DR,” https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/us-agricultural-exports-central-america-s-northern-triangle-prosper-under-cafta-dr#:~:text=Guatemala’s%20top%20agricultural%20imports%20from,export%20destination%20for%20U.S.%20agriculture.

[33] “How Covid-19 is threatening Central America’s economic lifeline,” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-52550389

[34] “Desempleo sube y llega a su mayor porcentaje en 10 años todavía sin reflejar los efectos de la covid-19,” https://www.nacion.com/economia/indicadores/desempleo-sube-a-su-maximo-valor-en-10-anos/N5FIK7DHLVBJJGQIW67BANJIWQ/story/

[35] “Desempleo y reducción de ingresos agobian a costarricenses durante la crisis del COVID-19,” https://www.ucr.ac.cr/noticias/2020/04/28/desempleo-y-reduccion-de-ingresos-agobian-a-costarricenses-durante-la-crisis-del-covid-19.html

[36] “Sector agropecuario ha tenido crecimiento significativo en los últimos 12 años,” https://www.el19digital.com/articulos/ver/titulo:87126-sector-agropecuario-ha-tenido-un-crecimiento-significativo-en-los-ultimos-12-anos

[37] “Nicaragua expone plan nacional de producción 2020 a organisaciones no gubernamentales,” https://barricada.com.ni/nicaragua-expone-plan-nacional-de-produccion-2020-a-organisaciones-no-gubernamentales/?fbclid=IwAR0YlfvREfaBeYC-_8YQxXFAJNeCdUQIWAWni6JVouDJF-0XJXIDtSETBmI

[38] https://viacampesina.org/en/what-are-we-fighting-for/biodiversity-and-genetic-resources/

[39] “Peasant Training Doesn’t Stop: IALA Ixim Ulew Now Online,” https://friendsatc.org/blog/peasant-training-doesnt-stop-iala-ixim-ulew-now-online/

[40] “CLOC-Vía Campesina Returning to the Countryside,” https://viacampesina.org/en/cloc-via-campesina-returning-to-the-countryside/

[41] “Nicaragua Battles COVID-19 and a Disinformation Campaign,” http://www.coha.org/nicaragua-battles-covid-19-and-a-disinformation-campaign/

[42] “USAID, Monsanto, and the real reason behind Delhi’s horrific smoke season,” https://www.ecologise.in/2018/10/20/the-real-reason-for-delhis-annual-smoke-season/

[43] “Henry Kissinger’s Food Occupation of Iraq Continues to Destroy the Fertile Crescent,” https://mintpressnews.ru/kissingers-occupation-iraq-destroys-agriculture/226407/

[44] “USAID and GM Food Aid,” https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/USAID_and_GM_Food_Aid.htm

[45] “The Monsanto Effect: Poisoning Latin America,” https://earth.org/the-monsanto-effect-poisoning-latin-america/ and

Website: https://en.centralamericadata.com/en/search?q1=content_en_le:%22Monsanto%22

[46] Kaufman, “US Regime-Change Funding Mechanisms,” in Live from Nicaragua: Uprising or Coup? pp. 173-188, https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.161/jwp.e46.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/live_from_nicaragua_june_2019.pdf.

[47] Zeese and McCune, “Correcting the record: what is really happening in Nicaragua?” in Live from Nicaragua: Uprising or Coup? p. 182, https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.161/jwp.e46.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/live_from_nicaragua_june_2019.pdf

[48] “NicaNotes: Peasant Women Take Stance of Dignity in Face of Crisis,” https://afgj.org/nicanotes-peasant-women-take-stance-of-dignity-in-face-of-crisis

Feeding the people in times of Pandemic: The Food Sovereignty Approach in Nicaragua

June 22, 2020June 29, 2020 COHA

By Rita Jill Clark-Gollub (Washington), Erika Takeo (Managua), and Avery Raimondo (Los Angeles) “A nation that cannot feed itself is

About COHA

COHA’s mission actively promotes the common interests of the hemisphere, raises the visibility of regional affairs and increases the importance of the inter-American relationship, as well as encourage the formulation of rational and constructive U.S. policies towards Latin America.

The Council on Hemispheric Affairs (COHA) is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt non-profit independent research and information organisation.

You can contact us by email:

Council on Hemispheric Affairs, COHA

P.O. Box 42730

Washington DC, 20015

Copyright © 2020 COHA. All rights reserved.