Mangrove destruction to make way for a shrimp farm, Nicaragua

Mangrove destruction to make way for a shrimp farm, Nicaragua

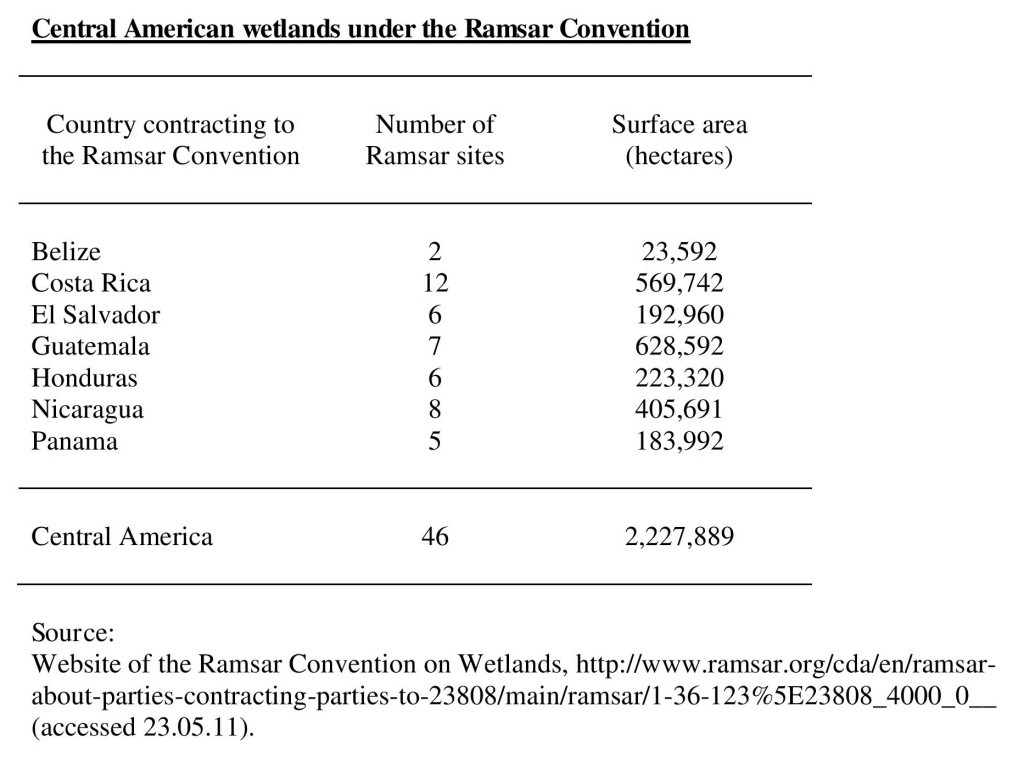

This figure is referred to in the book as Table 6.3 (Page 126)

The expansion of shrimp aquaculture in Honduras began in 1972. By 2010, it remained without any plan for its development and expansion. The only mechanisms controlling its growth are shrimp diseases, the fall of international shrimp prices, falling demand and sometimes pressure from local communities. The destruction, pollution and displacement of communities plus the plundering of natural resources have given rise to a social movement aimed at reducing its impacts. The NGO CODDEFFAGOLF has led the movement since 1988 and set its objective to achieve the declaration of Wetland Protected Areas in the Gulf of Fonseca.

In July 1999, during the Ramsar Convention held in Costa Rica, Honduran shrimp farmers (ANDAH) were surprised by the announcement that wetlands of the Gulf of Fonseca had been designated as ‘Ramsar sites’ (30,304 ha.), which became the #1000 site among the world’s wetlands. … On 20 January 2000, this ‘site’ was included in the Protected Areas of the Gulf of Fonseca (81,378 ha.) by Decree 5-99-E of the National Congress. ‘La Berbería’ was assigned 2,293 hectares of wetlands.

A few months after the publication of the Decree, a Spanish company known in Honduras as the ‘El Faro’ of Mr. Jaime Soriano, disrespecting the Ramsar Convention, national laws and without an environmental license, converted over 100 hectares of wetlands in La Berbería’s protected area into shrimp ponds. Complaints, demonstrations and protests of fishermen were of little use. The El Faro company, supported by the police and the complicity of government officials, had its way. It forced fishermen to negotiate inadequate compensation measures.

Meanwhile the EMAR I company expanded without an environmental license over tens of hectares.

In 2004 the Central American Water Tribunal condemned the government of Honduras and the shrimp farms El Faro, Sea Farms of Honduras and the World Bank for pollution and destruction of wetlands. The verdict was an ethical and moral conviction, and therefore did not result in any punishment.

2008: Destruction was spurred by high international demand for shrimp. In 2008 CODDEFFAGOLF presented a complaint during a Workshop on Protected Areas attended by regional and central authorities. It presented images of La Berbería where shrimp farmers had been caught red-handed using 6 tractors to destroy hundreds of acres of wetlands without an environmental license. The authorities ordered a halt to operations but they were resumed the next day to finish the shrimp farm which is called EXCASUR.

On 26 January 2010, EMAR II was granted an environmental permit for construction of shrimp farms in 169 hectares by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (SERNA) in a unique process which lasted only 5 days. It also gave a license to EMAR I that was operating for several years without an environmental license.

EXCASUR, which had earlier been punished for environmental crimes, waited for EMAR II to finish its shrimp farm with impunity before expanding its own on tens of hectares, claiming to have an environmental license dated 15 December 2009.

The irony and cynicism is that in all these cases the police and army have been protecting operations, equipment and facilities of the shrimp farmers. The President of the Honduran Council of Private Enterprise (COHEP) said: “We need more security because while farmers in the Lower Aguán try to recover land, in the south (Gulf of Fonseca) they have ‘seized’ a shrimp farm and this cannot be allowed because it will scare away investment.”

The granting of environmental permits that led to the expansion of aquaculture within Ramsar site #1000 in La Berbería did not consider the General Environmental Law. It did not respect the National System of Environmental Impact Assessment. It did not respect the Protected Areas Act 5-99-E. It did not respect Site Ramsar #1000 or the guidelines of the Management Plan.

On 5 March 2010, over 80 hectares of wetlands were converted into shrimp farms in the Gulf of Fonseca in addition to thousands of others that had already been converted. In La Berbería, wildlife has lost most of their habitat and fishermen have lost or are struggling for access to the mangroves and food sources for survival. …

As the insatiable demand for shrimp continues in Europe, Japan, USA and Australia, wetland ecosystems continue to disappear. Does it matter?

Extracted and adapted from Jorge Varela Marquez (March 2010) ‘Consumerism in developed countries causes destruction of wetlands in the tropics’, CODDEFFAGOLF, Honduras.

Also in Honduras, journalist Diego Cevallos has reported a “marginalisation and expulsion of fishing families in the shrimp farming areas, a loss of access to traditional fishing sites and a decline in the fish catch.”[1]

The brief details given of these few examples and others in ‘The Violence of Development’ book and the associated website show that the expansion of industrial aquaculture (farming of shrimp and other seafoods, especially tilapia and salmon) has been responsible not only for the loss of mangroves but also for environmental pollution, biodiversity loss, livelihood destruction of local communities and violence.

[1] Diego Cevallos (November 2010) ‘Shrimp industry devastating mangrove forests’, Tierramérica, citing Saúl Montufar, CODDEFFAGOLF spokesman.

Mangroves, Yes – Shrimp farms, No