Honduras: Murder never went away

October, 07 2008 | By Alison Bracken* | Source: Le Monde Diplomatique | Reprinted from ZNet

Life is cheap in Honduras and those who defend human rights themselves need protection – sometimes armed protection, reluctantly supplied by the government.

The young soldier stands nonchalantly outside a front gate, AK47 over one shoulder as he chats on his mobile while keeping an eye on the street. “No, I’m not afraid to use it,” he says, so bemused by the question that he lowers his sunglasses. “I’ve been well-trained. It’s an honour to protect Padre Tamayo. He protects the environment and helps the community. No one’s attacked him while I’ve been working.”

Gustavo Alberto Ordonez, 19, is one of 10 armed soldiers who guard Padre Tamayo, the renowned priest and environmental leader in Honduras. The armed guards are a necessary precaution. The priest has a $40,000 bounty on his head and has survived four kidnap and murder attempts, including an incident in 2006 where a live grenade was forced into his mouth.

He is a member of MAO, the Environmental Movement of Olancho, an area of the country with vast forests. The group supports responsible deforestation but opposes the current situation, in which international logging companies were given free rein by government to strip the forests bare of timber, destroying the natural environment and its water sources. Local communities do not benefit from this development, but are hired as cheap labour, and the timber is immediately shipped out of the country. Continuous flooding because of extensive deforestation is a major problem: the memory of the devastation Hurricane Mitch caused in 1998 is still fresh in people’s minds.

The group defends the rights and land of locals in these communities by blocking roads, initiating strikes and publicly denouncing abuses by logging companies. Because it challenges powerful economic interests, its members have been murdered, attacked and intimidated. In December 2006 two of Padre Tamayo’s MAO colleagues, Heraldo Zúñiga and Roger Ivan Cartagena, were murdered by national police agents outside the mayor’s office in Guarizama, in front of local people. Just two days before his murder, Zúñiga had told people about death threats from Salama-based loggers employed by the Sansone logging company. A local police sergeant, with accomplices, did the killing, and up to seven policemen may have been involved. Four were awaiting sentence when three mysteriously disappeared from custody last year.

The hiring of police as killers is commonplace. Honduras had death squads active through the 1980s, the most notorious of which was Battalion 316. Hundreds of teachers, politicians and union bosses were murdered by government-backed forces. The human rights defenders we met all said that the death squads never went away, they were just moved to other roles within the police or hired as muscle for private security firms.

The country seems controlled by private interests; even the democratic government was placed there by people with money and influence. The government is so compromised by the church’s authority and deals done with big business that it has no power to effect change. Padre Tamayo believes it’s only a matter of time before the one remaining policeman in custody for the murder of his two colleagues also escapes. “We expect he’ll be allowed to escape too. The police will never bring the police to justice.”

Champion of the people

He fears for his life but his knack for talking gunmen around has earned him the affectionate nickname “the Wizard”. At a mass MAO rally in 2001 to block a road where raw timber was travelling, fights broke out between protestors and police. Padre Tamayo was isolated by the head of the local police, who forced a live grenade into his mouth before moving quickly away. “I took it out and threw it as far as I could. It exploded in a nearby field,” he says, smiling. “Now the police have a case against me for causing a disturbance.”

He had recently been walking around his small village when an armed group tried to take him by force to a vehicle. Luckily, a couple of his soldiers were present and the kidnappers scarpered when they fired shots into the air. The Inter-American Human Rights Court ordered the Honduran government to provide protection for him after three attempts on his life in 2006.

Many international logging companies have hired Hondurans to murder the priest but repeated attempts have failed. He’s revered by rich and poor as a champion of the people. The first potential killer had a crisis of conscience and left the country. “He got in touch and told me what the logging company paid him to kill me, but he couldn’t do it. He told me to watch myself.”

The final attempt on his life before the government finally provided protection was perhaps the most extraordinary. He was alone in his presbytery when an armed group, including several soldiers, broke in. They planned to kidnap him and kill him elsewhere, uncomfortable with spilling blood in a presbytery. He talked them out of it. Stunned locals watched the men leave the house later. “I don’t know. When I’m confronted, I’m not a little mouse. They are nervous about what they are doing and I just talk to them,” he says. “They know if they kill me, there will be major consequences. The people would rise up and no timber would leave here.”

Instead, less high-profile environmentalists are being targeted, like René Gradis, co-coordinator of MAO. He has survived two attempts on his life and a kidnap attempt. He takes us to Un Corte, where once stood a sprawling forest, but now the only remaining trees are those not worth cutting down. When we reach the top of the steep mountain, the view is stark. All that can be seen is bald, treeless hills. “Yes, of course I’m scared for my life,” says Gradis. “But these thieves are taking our trees. We have to stop the wood thieves and the only way to do it is to keep denouncing what they do.”

Gradis has lost more friends to this cause than he cares to remember, but there is reason for optimism. The corrupt Honduran Forest Development Corporation (Cohdefor), which ignored logging companies’ blatant flouting of forestry laws in exchange for kickbacks, has just been replaced by Independent Forest Monitoring and new laws have been introduced. MAO also prevented Cohdefor employees from moving into the new organisation, positioning themselves at the table to influence policy.

We drive north to La Muralla national park to remind ourselves what a forest should look like. There is no management of the park, meaning some rare species are disappearing. But it still gives Gradis hope. “They have murdered our friends and we have yet to get justice. But what has happened gives us strength. We will not stop. We will keep fighting because of their deaths.”

`Lawyer of the poor’

Life is cheap in the capital, Tegucigalpa. Outside every restaurant and shop, security guards brandish rifles as a warning to customers and criminals. But the armed men are in real danger. The average wage in Honduras is between $100 and $150 a month. The guns the guards carry are worth far more than their lives and they are regularly murdered for their weapons. Dionisio Díaz García, “lawyer of the poor”, was representing private security guards whose labour rights were being violated when he was assassinated on 4 December 2006. He had driven to the Supreme Court to prepare for a hearing and, as he neared the court, he was shot dead by a man riding pillion on a motorbike.

García worked for the Association for a More Just Society (AJS) in Tegucigalpa. A week before the assassination, one of his colleagues received a text message warning that his life was in danger. AJS president Carlos Hernández has been threatened and intimidated since García’s death and now has full-time armed state protection, as does another employee who works for the Christian organisation that promotes economic, social and cultural rights.

Since Dionisio Díaz García’s murder, life has been a struggle for his widow Lourdes and her eight-year-old son, Mauricio. Such is her concern for their safety that she doesn’t want their faces to appear in the press. She’s completing a law degree and hopes to follow in García’s footsteps by representing the exploited and vulnerable. “I’ve tried to be a valiant person, and I’d like to follow in his footsteps. My husband wanted me to finish college. I’m doing it for him. I live by myself with my son. I believe I’m in danger and I cannot trust the police. When he was murdered, it was completely out of the blue because he never spoke of the work he was involved in. It was like cold water being poured over me.”

In January 2008 two men suspected of involvement in the killing were arrested and are currently in custody awaiting trial. But Lourdes and the AJS believe they were paid assassins and worry that the private security firm they believe ordered the murder won’t be brought to justice. “My husband was a very humanitarian man, loved by society. He dedicated his life to defending the poor. He didn’t care if someone had money to pay. For everything he did, he deserves justice. My son is always remembering him.”

New disappearances

García was one of 29 lawyers killed in the past two years in Honduras. A judge has also been murdered. Across the city, Bertha Oliva was reeling from a break-in at her office the week before, when the burglars urinated all over the floor. “It’s the first time after 25 years of working in human rights that I want to give up. Of course I won’t. But when I left my office at the end of the day, I cried.” She has a fair idea who’s responsible but is waiting until she has all the facts before making a public announcement. Oliva founded the Committee for the Defence of Prisoners and of the Families of the Disappeared (Cofadeh) and it’s the second time her premises have been ransacked in two months. They took files, computer equipment and personal effects. The group was initially set up to trace what happened to the hundreds of people who were “disappeared” by state security forces in the 1980s. The official number of disappeared stands at 184 but it is believed there are hundreds more.

Oliva’s interest is deeply personal. In 1981 her husband Tomás Nativí was forcibly abducted from their home by masked men. She never saw him again. The pair had married secretly and she was pregnant with their first child at the time. Nativí was a young revolutionary who had left the Communist Party to set up his own political group.

Cofadeh’s work has expanded far beyond examining what has happened to the disappeared. It is now legally representing families of environmentalists who’ve been murdered in their cases against the state. “We thought that the whole issue of disappearances was something that had been consigned to the past but in two-and-a-half years, seven people have disappeared. We are now seeing the same pattern of assassinations, torture and killings as we did in the 1980s.”

Oliva’s car has been followed in recent weeks and she feels as vulnerable as when her husband was taken 27 years ago. She’s involved with the development of a memorial park and exhibition centre outside the city that will pay homage to the 184 people officially disappeared. A tree has been planted to represent each person and a flame of memory will burn bright. She purchased the land from an Irishwoman and swears when the project is completed she’ll retire from the organisation and her 70-hour working week. “The state right now is weak and it has failed. I am here to give it strength. The day my voice will cease to be heard is the day I prefer to disappear physically myself,” she says. “They can kill me with guns, but they will never kill my spirit. If I had to do it all again, I wouldn’t hesitate. I’d go through it all again. For him.”

`If I had a gun, I’d shoot you’

Dusk is falling as Donny Reyes and his boyfriend walk hand in hand through the busy streets of Tegucigalpa. Two men across the road begin shouting obscenities at them. One of them spits on the ground and screams: “If I had a gun, I’d shoot you.” This is nothing compared to what Reyes has lived through. They held hands publicly to facilitate our photograph; they would not usually take such a risk in this violently homophobic country, where the Catholic church has extreme influence and ran TV and radio campaigns denouncing the “evil of homosexuality”.

Reyes is treasurer of a rainbow gay group, Arcoiris, in Tegucigalpa. His tale has won international attention and raised awareness about the dangers and discrimination the gay and lesbian community face. “It still hurts to tell the story,” he says, “but what hurts more is that this kind of thing is still happening here.”

In March 2007 Reyes left the Arcoiris office late at night with a friend and supporter of gay rights, Doña Blanca. Six police officers approached him and demanded to see his identity papers, which he produced. He explained who he was and where he was coming from. The police then let Blanca go but arrested Reyes. “They beat me with batons and threw me into the car saying `queers don’t have rights’.” At the police station, the police took some time choosing which cell to put him in, looking for the one with the most gang members in it. Eventually, they brought him to a cell with some 60 prisoners and told them: “Here’s a present for you boys. You know what he is and what to do.” He was gang-raped by six men after being stripped and beaten. “It was a very small and dark room. I ended up in a pool of shit and urine.”

Released from prison the next day, Reyes immediately had medical tests and endured an agonising wait before he found out that he hadn’t contracted HIV or another sexual infection. Next stop was the police station to make a formal complaint. The chief of police advised him it wasn’t worth pursuing and advised him to leave the country. But Reyes persevered and charges were eventually brought against several policemen for illegal arrest. He had a witness, Doña Blanca, who was willing to give evidence. But weeks before the trial was to begin, she was shot dead in her home. All charges against the policemen were dropped in the Supreme Court earlier this year.

The same month Reyes made the complaint, Arcoiris’s office was broken into and documents and computer equipment were stolen. The office has been broken into a couple of times since. “I feel threatened and in danger,” he says. “But we have to keep on doing our important work until we have equal rights.”

Since Arcoiris was founded seven years ago, 210 people from the gay community have been murdered in hate crimes. Gay rights leaders believe a lot of this hatred stems from the influence of religious fundamentalism. In 2004 the church described it as “unfortunate” and “to be repudiated” when three gay organisations were granted legal status. The church has considerable sway with the government and influences political decisions that contribute to the stigmatisation of this community. Three years ago the cardinal of Honduras, Oscar Andrés Rodríguez, objected when Arcoiris rented an office down the street from a church building. The group was evicted from the premises immediately.

The group’s new premises is a busy drop-in centre. Many of its visitors are teenagers thrown out of home by their parents because of their sexuality. They speak about dropping out of school because of beatings from their peers and intolerance from teachers. Many then drift into prostitution. “I’ve been beaten and attacked and seen it happen to all my friends. I’ve tried to kill myself too,” says Ray Saene, 18, who’s been living with prostitutes since her mother threw her out of their home because she’s a lesbian. “I’m scared every minute.”

* Alison Bracken is a journalist

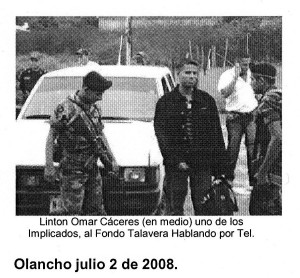

The four assassins who carried out the machine gun execution were members of the local police – Linton Omar Cáceres Rodríguez, Rolando Antonio Tejeda Padilla, Juan José Talavera Zavala and José Arcadio González. Despite a history of impunity for those who commit such crimes in Honduras, the four were detained and were convicted by a Honduran court on 1st July this year.

The four assassins who carried out the machine gun execution were members of the local police – Linton Omar Cáceres Rodríguez, Rolando Antonio Tejeda Padilla, Juan José Talavera Zavala and José Arcadio González. Despite a history of impunity for those who commit such crimes in Honduras, the four were detained and were convicted by a Honduran court on 1st July this year. uld want us to2nd July in Olancho: Linton Omar Cáceres (in the middle) and Juan José Talavera (on the phone) in army custody believe that they escaped on their own? Who is it who has helped them to escape justice? Who is behind their escape? Is it the same people who Who was responsible at the Brigade 115 installation when they escaped? Where were these people when they escaped?

uld want us to2nd July in Olancho: Linton Omar Cáceres (in the middle) and Juan José Talavera (on the phone) in army custody believe that they escaped on their own? Who is it who has helped them to escape justice? Who is behind their escape? Is it the same people who Who was responsible at the Brigade 115 installation when they escaped? Where were these people when they escaped?