´Proyecto Sol´ or Project Sun was established through the Nicaraguan organisation ADIC (Integral Community Development Association), based in the city and department of Masaya. This is “a forgotten region between the country’s two largest lakes”[1] dominated by large rice farms and big landowners. Multiple small communities inhabit the margins of the large rice farms. Power lines can be seen running over these rural communities but apart from a few houses, the electricity is devoted to pumping water through the farms’ thirsty irrigation systems and thus the workers live in darkness. Unless the privatised electricity grid is extended (unlikely – see the case study on privatisation in Nicaragua earlier in this chapter), remote neighbourhoods will never have the privilege of this requisite and the energy crisis will persist.

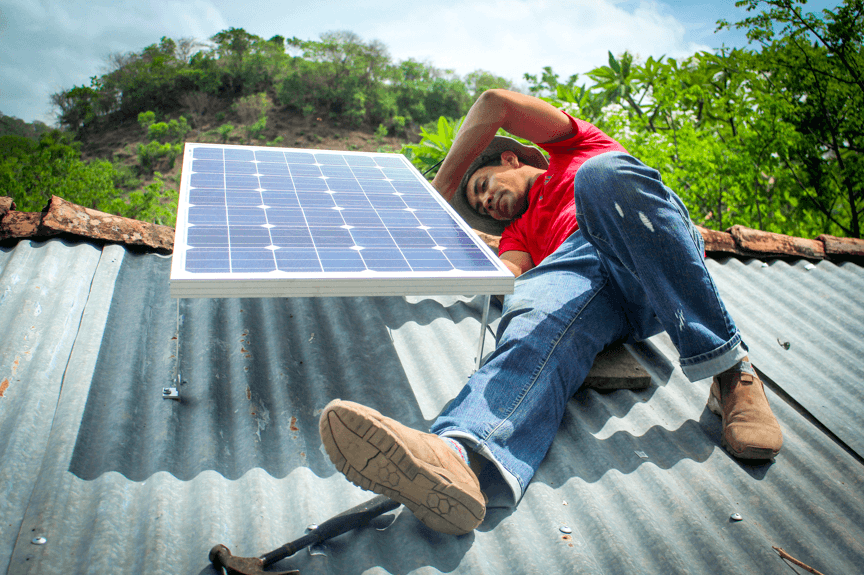

Being a green and reliable source of electrical power, solar panels are an obvious solution to this problem. Previously only wealthy families had the capital to purchase the equipment, but with the nature of ADIC´s repayment schemes, poorer families can repay the $700/£500 cost over a period of 5-7 years, based on what they can afford each month.[2] The cost is no more than that which would be paid for electricity from the national provider, and the repayments are used in a revolving fund for further reinvestment.

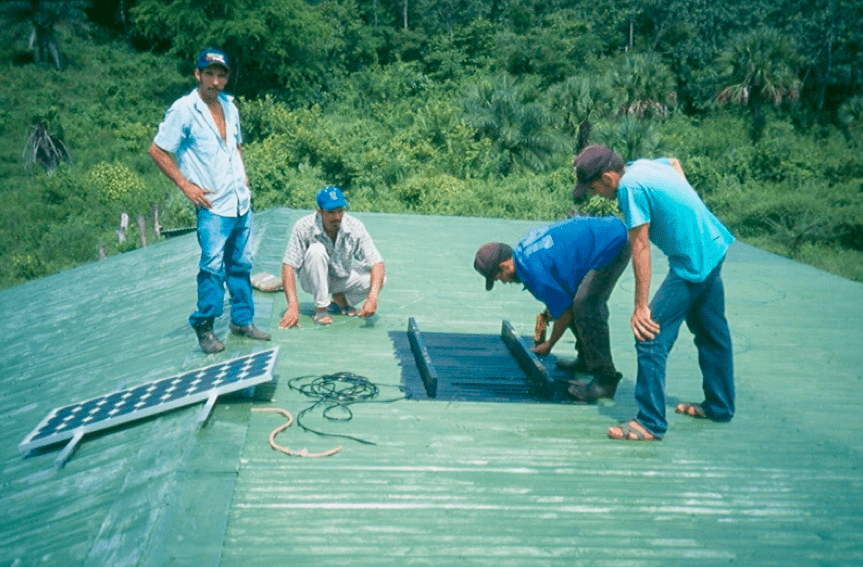

To July 2010, 135 solar panels have been installed in 15 different communities, and the demand is increasing. Once 200 kits have been installed, the repayment account will be healthy enough to provide 25-30 new panels per year.[3] The micro-loan fund is one of this project’s key success factors and it has proven to be a potential application for vulnerable communities throughout Central America.[4]

One such success story is that of Señora Amada Concepción – the recipient of the one hundredth solar panel kit to be installed. She and her community live without electricity in an area of low lying marshland in the district of Tisma. Equipment was brought in by horse and cart as the connecting road is impassable.[5] The family now have electricity for the first time.

Although surveys done by Proyecto Sol reveal that initially communities are sceptical about solar energy, house owners are rapidly converted to the scheme once the preliminary demonstration equipment is seen to work even on cloudy days during the rainy season.[6] The output of each panel is enough for 3 or 4 light bulbs, as well as a socket for use by a TV or radio for a few hours a day.

The project coordinator is Englishman John Perry, now a permanent resident in Masaya. Through his contacts with British based Housing Associations, he and ADIC have ascertained the capital to initiate Proyecto Sol and other schemes which aim to improve infrastructure for low income families in Masaya.

[1] ADIC (March 2010) ‘We own the land, water, electricity…’, Agrovivenda Bulletin , No.21, ADIC.

[2] John Perry, project coordinator, interviewed especially for this book, 20 July 2010, Masaya, Nicaragua.

[3] John Perry (Winter 2008) ‘Sun lights off-grid communities in Nicaragua’, Central America Report, www.central-america-report.org.uk

[4] Matthew Barker (23 January 2009) ‘Out of the darkness’, Inside Housing, p.36-37.

[5] ADIC (September 2008) ‘First 100 Solar systems installed’, Agrovivenda Bulletin, No.18, ADIC.

[6] Op.cit, Perry (2008).

In Belize, having bought the island of Blackadore Caye in 2005 (for US$1.75 million in partnership with Jeff Gram, owner of the exclusive Cayo Espanto Resort), Leonardo DiCaprio has drawn up plans to turn it into a luxury resort based on sustainable design, using solar power, for instance, for the landing strip.[vii]

In Belize, having bought the island of Blackadore Caye in 2005 (for US$1.75 million in partnership with Jeff Gram, owner of the exclusive Cayo Espanto Resort), Leonardo DiCaprio has drawn up plans to turn it into a luxury resort based on sustainable design, using solar power, for instance, for the landing strip.[vii]