Shortly after the inauguration of Alejandro Giammattei as the new Guatemalan President, he met with President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador and offered a deal of potentially great benefit to El Salvador: namely a port on the Atlantic coast of Guatemala. Lucy Goodman translated and summarised articles about the deal from La Prensa Gráfica (by Melissa Pacheco, 28.01.20) and El Economista (29.01.20), and Martin Mowforth added various commentaries on these for The Violence of Development website.

March 2020

Key words: El Salvador – Guatemala integration; Atlantic port; security cooperation; domestic flights.

El Salvador and Guatemala plan to eliminate the border initially for the passage of persons and later for freight. They have also re-defined flights between the two countries as ‘domestic flights’.

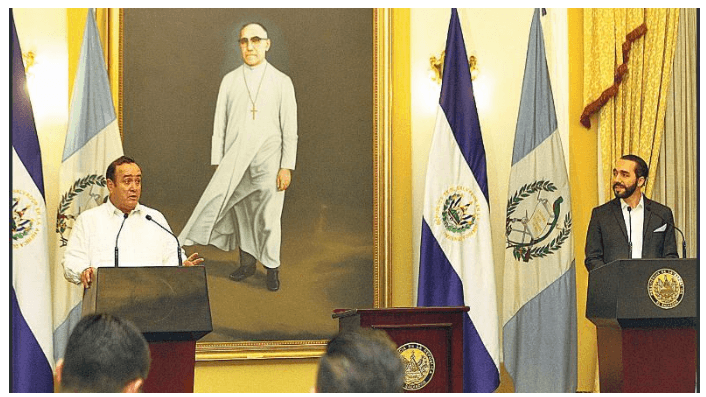

(Melissa Pacheco) The presidents share the announcements between themselves about the removal of the border for the transit of people and goods.

The Guatemalan president offered a concession to create a public-private partnership as the means to enable completion of a Salvadoran port on the Atlantic coast. Land from the Santo Tomás de Castilla National Port Company (Empornac) will be ceded to El Salvador for this purpose. The area to be ceded is known as El Arenal (or The Quicksand) and currently serves as a depot for containers. Last year (2019) Empornac carried out technical studies to determine the feasibility of constructing a pier to accommodate dredgers and cruise ships there.

“We have offered El Salvador something unprecedented in the history of Central American integration and today I want to announce it publicly because we’re going to explore, as soon as possible, the possibility of El Salvador having a port in the Guatemalan Atlantic. We will deliver this Project as a public-private partnership so that El Salvador can develop it. It is an offer that we have made to El Salvador, we consider it to be the right thing to do,” Giammattei announced at a press conference that took place at the Presidential House.

He added that he had spoken with the authorities of SICA (Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana / Central American Integration System) in order to receive the support of the institution in the implementation of the project. He also announced that he made a firm pledge to officially de-categorise flights between Guatemala and El Salvador to ‘domestic’. This comes as part of the initiatives to improve integration in the region.

The Guatemalan Minister of Economics, Antonio Malouf, confirmed that a legal-technical analysis for ceding the land of Empornac will be carried out.

“Basically, it would be our entry to the Atlantic. Our goods will have the power to go from the Atlantic and enter from the Atlantic. I believe what we’re doing is making a real union that is going to spread to other countries in Central America that will want to unite and do similar,” declared the Salvadoran President.

Apart from the possible construction of the Salvadoran port on the Guatemalan coast and the re-categorisation of flights, the leaders announced that in one month they hope to have removed the border for the passage of people and within three or four months the barriers for goods between the two countries.

“We have to sign papers where we can eliminate the customs on goods respecting that goods entering El Salvador and destined for Guatemala have already paid taxes in El Salvador and do not have to pay them in Guatemala and those that have entered Guatemala destined for El Salvador do not have to pay them in El Salvador. We believe it will take us about three months,” the Guatemalan president declared to the media.

The elimination of the borders for the passage of people also requires the implementation of a bi-national arrangement on security. “If someone passes from Guatemala to El Salvador evading an arrest warrant, they will not be evading anything because we are going to have the same approaches in both countries,” Bukele stated.

Giammattei referred to their intention to apply similar security sanctions, one of which was to standardise the criminal codes in both countries. In the language he used to explain this part of the agreement, Giammattei betrayed his profoundly hateful and hardline understanding of crime in society. “Standardising the penalties, the sanctions, the punishments, so that when they spray ‘Baygon’ here the cockroaches do not go there because they think that there they will find it easier, and when they spray ‘Baygon’ the cockroaches won’t come here, as the law will be the same for the two countries,” said the new president

Moreover, he said that they had been monitoring Bukele’s Territorial Control Plan (PCT), the main commitment of the Salvadoran Government to improve security conditions, and he (Giammattei) did not rule out implementing some of the same sanctions in Guatemala.