Over the last twenty years, the role of the Chinese in Central American development has grown. Of course it has not been entirely through altruism – China gains considerably from Central American resources. In October 2019 Alberto Belladonna of the Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI – www.ispionline.it/) produced a commentary on the geopolitical trends in the comparative influences of China and the United States on the region of Central America. We are grateful to Alberto and to the ISPI for their permission to reproduce the commentary in The Violence of Development website.

“The Monroe Doctrine is alive and well”, proclaimed former US National Security advisor John Bolton in April 2019, re-invoking an old vestige of American foreign policy dating back to 1823. A time when an infant United States was attempting to affirm its sphere of influence south of the Rio Grande, declaring that any interference in the region from European powers would be recognised as an unfriendly act against Washington. Bolton’s message, rather than to the “old European colonial powers”, was referring to new powers, as former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson already did one year before, when he warned Latin America against China’s new imperial power. A warning message aimed especially at South American countries but which also concerns Central America (CA), an often-neglected region but with a strategic geopolitical role in the current context of big-power confrontation.

The United States: Central America’s “Big Brother”

Since the foundation of the United States, for Washington CA has always represented a natural sphere in which to extend its geopolitical presence. An inseparable bond, sometimes too tight: “So far from God, so close to the US” Porfirio Diaz, president of Mexico in the end of nineteenth century, once said. But, how could CA not be so close to the United States? A few sheer numbers are sufficient to underline the role played by the US as gravitational pole for the whole region.

Washington has always been the region’s main trading partner. Today, it still accounts for almost 47.5% of total exports and 40.6% of imports; more than doubling the volumes of the European Union (CA’s second trading partner with 24 % of exports; 9.6% of imports) and even surpassing inter-regional trade (which accounts for 30.8% of total exports and 14.8% of total imports).

The US and CA are also bound together by the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), a trade deal that goes beyond tariff-cutting and includes the protection of international property rights, investments and norms regarding public procurement procedures and financial services. CAFTA consolidated the role of the US as the major source of foreign direct investment (FDI) (27.3%) for the region, well ahead of the European Union (17.2%) and intra-regional flows (12.3%).

The US is also the major source of official development aid with annual average spending of $700 million between 2016 and 2017 focused on strengthening political, social and economic conditions in the region. In particular, through the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), the United States invested almost $500 million to combat criminal organizations and illegal trafficking in CA.

Finally, the US is also the main destination of migration flow from CA: in 2017, 3.5 million CA immigrants resided in the US. They play a pivotal role in developing their countries of origins with their remittances representing on average 7.5% of regional GDP, ranging from 0.9% in Costa Rica to more than 20% in Honduras. But they also constitute an important source of labour force for the US, as CA nationals register a participation rate higher than both the overall foreign and US-born populations. There is, however, a rising fear of a potential demographic revolution caused by uncontrolled Hispanic migration, as well-known political scientist Samuel Huntington contended in “The Clash of Civilizations” (1996) and later reiterated in his in-depth study “Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity” (2004). Indeed, Mexican and CA immigrants represent 37% of the US’s foreign-born population, and 71% of the country’s 11 million illegal immigrants. This last group was the main target of president Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign. Rising tensions culminated in April 2019 when Trump froze about $450 million of US foreign aid to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador due to their inability to limit migrant outflows to the United States.

China’s ‘Yuan Diplomacy’ in Central America

While the US seems eager to step back from the region, considered mostly a source of instability and constant mismanagement of aid and cooperation funds, China is silently advancing on the chessboard by extending its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to ‘America’s backyard’.

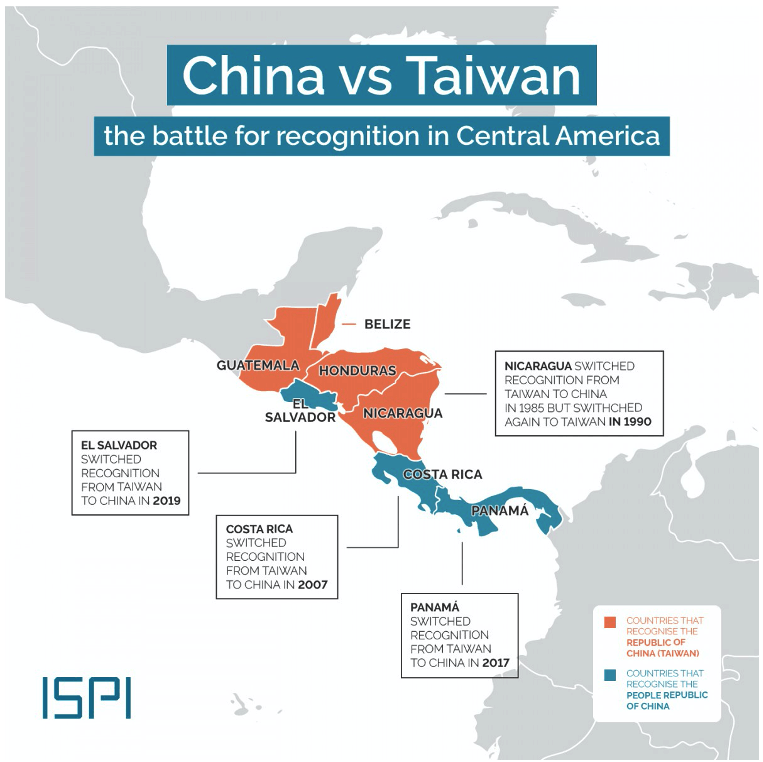

China’s presence in CA has been growing since the late nineties with a breakthrough in 2007 when Costa Rica became the first country in the region to end diplomatic relations with Taiwan. “An act of elemental realism, an awakening to the global context we are forced to deal with”, declared at that time Costa Rican president Óscar Arias. Indeed, elemental realism was at the core of Chinese interest in Costa Rica. A small market of almost non-interest for Chinese exports (0.25% of its total in 2018) Costa Rica became a strategic platform after the signing of a bilateral Free Trade Agreement in 2010, which allowed Chinese enterprise to indirectly exploit the US market through CAFTA. Beijing’s plans also called for Costa Rica to become a strategic platform to refine Venezuelan oil directed to China through a joint project worth $1.3 billion: a project that turned out to be a failure, overwhelmed by government scandals, legal restrictiveness and environmental abuse. Nevertheless, trade with China increased over the last decade at the annual rate of 14.9% with an increasing trade balance in favour of Beijing. Most importantly, in September 2019 Costa Rica decided to scale up its relations with Beijing by signing a memorandum of understanding under the umbrella of China’s BRI as well as by promoting the country’s plans to create a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Puerto Limón where Chinese products could be manufactured.

Yet the first CA country to sign a BRI agreement was Panama. With almost 6% of the total global maritime trade passing through the country, China’s main interest undoubtedly was the Panama Canal. After failing to create a similar infrastructure in Nicaragua, Beijing in fact invested massively in Panama, making the country the prime destination for Chinese FDIs ($2.5 billion) in the region. Among major projects, in May 2016 China Landbridge, a privately owned company, bought Panama’s largest port located on Margarita Island. The investment in the Panama Colón Container Port (PCCP), which cost over US$1.1. Chinese Overseas Shipping (COSCO), another key player in the area, also decided to expand its operations on the Atlantic side of the canal. Finally, China also focused on the free port of Colón, where tons of Chinese products are disembarked, transformed and reshipped to Latin America and the US. Here, Huawei installed its sixth global distribution centre.

China’s pragmatic attitude did not prevent the country from doing business with Panama even before formal diplomatic ties were established between the two countries. The same goes for China’s business relations with Guatemala and Honduras, two countries that are still close to Taiwan. Indeed, from 2006 to 2016 Chinese exports to Guatemala and Honduras increased by 300% and 750% respectively. Chinese products found a very receptive market in CA: on the one hand, they were not required to follow the same strict standards of Western markets. For example, China has become the second exporter of vehicles to Guatemala and Honduras with a market share of 11.75% and 14.75% respectively. On the other, thanks to lower prices, China gives CA the chance to access a larger range of products, which would have been impossible otherwise.

The frontrunner of China’s expansion in CA is Huawei. In fact the company has built telecommunication networks throughout the region, works with most major telecommunications providers such as Millicom, and is ready to build an underwater cable link between China and Latin America. A situation which is prompting concerns from the US, which released a document stating that “China’s aggressive telecommunications investments in the region raise security concerns about placing the region’s communications backbone on Chinese networks; an increasing portion of data and message traffic will flow through and come to depend on, Chinese-supplied infrastructure”.

Still, China’s interests in the region are more subtle. Increasing its relations with CA will indeed also increase China’s negotiation power when it comes to Asia Pacific and the South China Sea: a wild card to play switching their respective backyards.

Future perspectives

But is CA de facto shifting into China’s orbit? Probably not. Last May, Mexican president Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador and the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) presented the Comprehensive Development Plan for Central America, which sets an investment of about $30 billion in production and infrastructure projects in CA. The objective is to integrate CA and Mexico in a way that could also serve the US market through the newly established United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Although Trump thwarted this project with a new clause, which imposes a minimum wage of $16 per hour in those factories that export cars to the US, CA’s future remains tied to closer integration with the US. Against the backdrop of the ongoing trade tensions between China and the US, CA could benefit from the ongoing decoupling process and a more regionally integrated value chain intercepting more delocalization process from North America. CA is indeed meant to remain bound to the US. However, China will not cease to exploit the US’s inattentions and negligence to increase its influence, as if the two were engaged in a long-term game of Go.