19 September 2012 | By Danilo Valladares

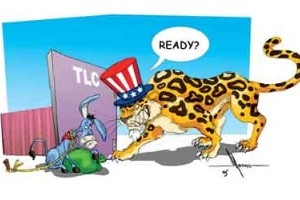

The Association Agreement between the EU and Central America could exacerbate sustainability problems in this Latin American region.

GUATEMALA CITY, Sep 17 (Tierramérica).- The Association Agreement between Central America and the European Union (EU) will increase environmental and social pressures on the region, warn experts and activists. But some observers stress its potentially positive impacts.

“We can expect an increase in the activities of extractive industries,” which bring about “negative environmental and social repercussions,” said Juventino Gálvez, the director of the Institute of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment at Rafael Landívar University, a Jesuit university.

This is a delicate issue in several countries of the region. In Guatemala, for example, Montana Explotadora, a subsidiary of the Canadian mining company Goldcorp, has been accused of contaminating rivers and affecting the water supply of 18 indigenous communities in the western department (province) of San Marcos, through its activities at the Marlin gold mine.

In May 2010, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights called on the Guatemalan government to suspend the operation of the mine, but it continues to operate.

“National institutions are precarious, and there is a well-known tendency to disrespect legislation, which is vague and permissive to begin with,” Gálvez commented to Tierramérica.

The entry into force of the Association Agreement, signed on Jun. 29 by the EU, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama, depends on its ratification in the European Parliament and the legislatures of the six Central American countries.

The agreement establishes mutual commitments in three areas: political dialogue, cooperation and trade.

With regard to trade, it will eliminate tariffs on agricultural products (such as coffee, fruit, vegetables and meat), textiles and manufactured goods, while opening up markets to financial, telecommunication, transportation and other services, as well as government procurement.

As for cooperation, the agreement aims to promote technical assistance and exchange in the use of clean energies, mining, tourism, fishing, transportation, sustainable development and the environment.

The most significant section of the agreement with regard to the environment is found in this chapter, under Title V, which also addresses natural disasters and climate change – two key issues for the region.

In the area of political dialogue, one of the aims is to establish common ground in areas such as the rule of law, good governance, democracy, human rights, gender equality, the rights of indigenous peoples, poverty reduction and migration, among others.

For Gálvez, when the “potential” expansion of monoculture plantations is added to the equation, the result will be greater conflict “due to competition between agroindustrial operations and rural communities for access to strategic resources.”

Oil palm plantations, which tripled in size between 2003 and 2010, have given rise to violent land disputes, especially in northern Guatemala, where hundreds of peasant farmers have been displaced and a number have been killed in clashes with the police.

Miguel Mira of the non-governmental Center for Investment and Trade Research of El Salvador believes that “the only interest behind these agreements is to open up more markets to trade and investment for big transnational corporations, while labor and environmental issues are considered irrelevant.”

In Central America, with roughly 43 million inhabitants, half of the population is poor. And poverty is deeper in rural areas.

There is an obvious asymmetry with the EU, home to 500 million inhabitants and one of the wealthiest areas on the planet, which until now has represented barely 10 percent of Central America’s foreign trade.

In 2011, the EU sold 36 billion dollars in goods to Central America, and purchased the equivalent of 31.6 billion dollars, resulting in a trade surplus of 4.4 billion dollars for the EU, according to European Commission figures.

Central American sales are concentrated in telecommunications and office equipment (53.9 percent) and agricultural products (almost 35 percent in 2010). In the meantime, the main goods imported from the EU are machinery and transport equipment (48 percent) and chemicals (12 percent).

“The logic of the Association Agreement is that of free trade, and all other aspects of international relations are subject to this,” said activist Erik Van Mele of the international non-governmental organization Oxfam Solidariteit.

Although the agreement addresses sustainable development and the environment, there is no guarantee of protection for Central America, one of the regions with the greatest wealth in biodiversity in the world.

Article 284 on trade and sustainable development “stipulates that these matters are excluded from the procedures established for the settlement of eventual conflicts,” Van Mele stressed.

Moreover, there are various interpretations of sustainable development, he said.

For example, the promotion of agrofuels as “green energy” to replace fossil fuels “could give rise to deforestation to allow for the planting of monocultures, or to hunger caused by an increase in the price of corn, a staple food in the region, due to its high demand for conversion into ethanol,” he warned.

An evaluation of the agreement requested by the European Commission in 2009 concluded that, in addition to its economic and trade benefits, it would generate greater pressure on land, coastal and maritime resources, with a specific warning on the potential increase in monocultures. It also recommended measures to minimize the impacts, to be adopted in the framework of cooperation.

Gustavo Hernández, the coordinator in Brussels of the non-governmental Latin American Association of Development Promotion Organizations, told Tierramérica that the sanctioning mechanisms for non-compliance stipulated “are not binding” and that there is “little participation by civil society, particularly the majority sectors of the population who will be the most affected” by the agreement.

As far as Luis Muñoz of the Guatemelan Center for Cleaner Production is concerned, however, the experience of the free trade agreement with the United States, in force in Guatemala since 2006, demonstrates that agreements like these can generate positive demands.

“When the environment is linked to the economy, it is more advantageous for companies to invest time and resources in environmental aspects,” he explained.

Moreover, the transfer of technology and the drive for competitiveness also need to be considered, he added. “Before, the pressure to approve environmental laws was very low, but after the free trade agreement with the United States, regulations on wastewater were adopted,” he noted.

Muñoz recognizes that all industries generate impacts, but believes that it is necessary to “seek a balance.”

“Without the profits from coffee, for example, how many people would be left without an income? And I’m not talking about the plantation owners,” he said.

Source: Tierramerica | http://tierramerica.info