The following blog post by CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador) recently posted the following item relating to a real estate development of a ‘mini-city’ and its conflicts with the provision of water for over 60,000 people in Greater San Salvador. We are grateful to CISPES for permission to reproduce the post here.

January 17, 2020

El Salvador’s Social Movement Fights Mega-Development Project ‘Valle del Angel’, Citing Numerous Environmental, Social and Public Health Concerns

Key words: mega-developments; mini-cities; water; public service; Valle del Angel (El Salvador).

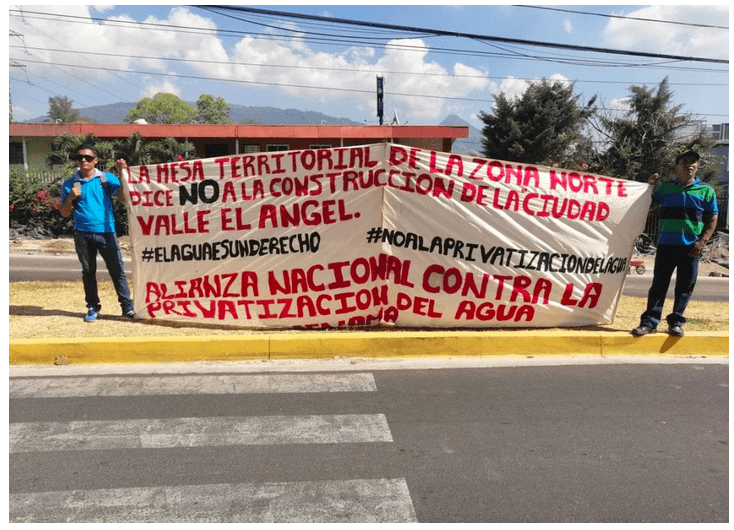

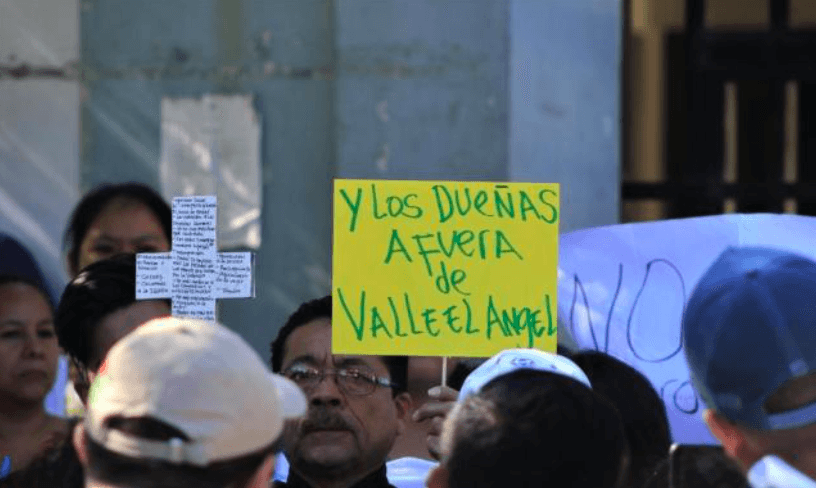

The social movement struggle to stop construction of the massive ‘Valle del Angel’ real estate development project has entered the new year with both increased threats and increased mobilization. Protests against the Dueñas family’s planned ‘mini-city’, which would comprise more than 500 blocks of residential and commercial space in northern San Salvador, began more than a year ago in the neighbouring communities of Apopa, Nejapa, and Quezaltepeque. Since then, environmentalists and organisers from a variety of sectors have formed a coalition to fight the behemoth enterprise together. The project is part of an alarming trend of mega-developments that have sprouted up across the country and region. Marketed as ‘urban’ and ‘modern’, they’re designed to be almost completely self-sufficient and typically boast everything from thousands of units of luxury housing (more than 8,000 units in the case of Valle del Angel), shopping, offices, and restaurants to hospitals, churches, hotels, and schools. Omitted from the marketing, however, are the profound negative impacts: siphoning of water from nearby rural populations (for whom water is already dangerously scarce); grave harm to both the environment and public health; further privatization of land and resources at the expense of public welfare; and an alarming intensification of the disparities between rich and poor.

Regarding the Valle del Angel project specifically, the social movement warns that because of its location in a basin that contains an important aquifer (i.e., underground layer of permeable rock or other sediment from which water can be extracted through a well or spring), it poses additional risks even beyond those mentioned above. The aquifer renders the area in question a significant ‘recharge zone’, supplying water to much of northern San Salvador. Environmentalists and ecologists have cautioned that the development would erode the subsoil and stress the reserves that undergird the zone; this, alongside contamination and other destabilizing effects, would decrease the aquifer output, threatening the water supply of more than 60,000 people in greater San Salvador. Further, the densely populated project would worsen traffic in an already heavily congested area, increase the risk of landslides, eliminate the habitats of a wide variety of wildlife, and destroy ecosystems and some of the last remaining forested regions of El Salvador.

The development has been in the works since at least 2009. At that time, however, the environmental commission under the FMLN denied the requested well-drilling permits on the grounds that they over-exploited the aquifer by exceeding the maximum allowable water extraction/flow rate, straining its capacity and putting the water supply at risk. But this June, just a few weeks into the new administration, El Salvador’s national water board, ANDA, stepped in to grant the permits, even though it was beyond their authority to do so. The social movement challenged the validity of the permits on these grounds as well on the same grounds the FMLN denied them – that in delivering a quantity of 400 litres of water per second, they exceed the allowable, safe, or sustainable rate. As of right now, the case sits at the environmental commission, where it is being debated.

The social movement struggle to stop development has been fiercely and increasingly vocal (though rarely covered by the mainstream press in El Salvador). Since the risks were presented in public forums last year, it has grown to include direct action, press conferences, government petitions, editorials, letters to the president, and appeals to El Salvador’s Supreme Court as well as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Public demonstrations escalated in the last months of 2019 after the social movement got word the developers had increased pressure on the environmental commission to grant the permits before the end of the year. More than once, protestors occupied the streets surrounding the environmental commission with their own demands and powerful voices of resistance: “Corporations out of our communities!” signs read. So far, they’ve been able to hold off the permits, but the threat persists.

The Valle del Angel development is not the first or only one of its kind. The encroachment of urban mega-developments as a mechanism of capitalist expansion is a disturbing trend in El Salvador and in the region. In addition to other industries like mining/natural resource extraction, agribusiness, and hydroelectric projects, urban real estate development is on the uptick as a means of ‘accumulation through dispossession’ and the ongoing transfer of wealth from the working class to elites. (All of which are among the root causes of destabilization and displacement we’re seeing across Central America.)

Further, with the election of Nayib Bukele, the social movement has become increasingly alarmed by his administration’s quick authorization of permits for similar projects that bypass checks on environmental impacts. In a letter sent to the President last summer, the movement voiced deep concern that he has “instructed his cabinet to accelerate the environmental permits held back by the previous government” and urged that “economic investment should not take precedence over the interests of the Salvadoran population.” Likewise, both the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman in El Salvador and the archbishop of San Salvador have criticised Bukele’s silence on the issue. Lastly, without a General Water Law, which the social movement has been demanding since 2006, there is limited legal recourse and no guarantee of water as a human right.

If the term ‘neoliberalism’ sometimes seems hard to pin down, the Valle del Angel project is a telling image of the world neoliberal policy seeks to advance: oases of luxury amid widespread, water-, food- and land-scarce poverty: a world in which exorbitant price tags keep the poor – and poverty itself – out, while limited resources are hoarded within. Resistance to the Valle del Angel has a place alongside other struggles in El Salvador (like the case of the Tacuba water defenders) in being emblematic of the fight against that neoliberal vision. And El Salvador’s struggles, in turn, take their place among other popular resistance movements around the world – from Ecuador to Chile to France to India and beyond – filling the streets daily, demanding a different, socialist, egalitarian world instead.

CISPES will continue to report on this issue, but also follow the Foro del Agua, the Alianza Contra la Privatización del Agua, ECOS El Salvador, and ARPAS for regular updates.