By Ana Ella Gómez, Centre for the Defence of the Consumer, El Salvador

The Centre for the Defence of the Consumer, where I work, is part of a citizen campaign called Blue Democracy that aims to reclaim the human right to water in El Salvador. We are strengthening a multi-sector alliance in which the common point of departure is the defence of water. …

We are now working on a campaign to reform the country’s constitution and get water recognised as a human right. … We are also working on a proposed water policy that deals with three main types of services: state, municipal, and communal. In the case of El Salvador, we’re convinced that we have to claim the public water supply by strengthening the public company that already exists [ANDA]. We want an efficient public company but we also want a public company with public participation. We also want to strengthen the municipalities that provide good local development with participation by the people. ….

One of Latin America’s victories has been the belief that water must be in public hands, must be held by the community, that the people have the power to make their own decisions and that, whether a company is public or is communally owned, it is essential that the citizens, the men and women, participate in strategic decision-making. …

In the end, what do we want? We want people to be able to not just share their opinions, but also to make their own decisions. Each model must be based on the reality of each community and each community needs to define what type of public, community set-up meets its populations’ needs. We want a commitment to protect our water, a commitment made by everyone, a shared responsibility. We want a system in which service providers are also responsible for protecting and taking care of the water. ….

Right now, our biggest advantage is that we have constructed our own alternative and the commitment to defend it. Our successes so far demonstrate that another way is possible. But the threats continue. Neither the multilateral institutions nor the big corporations are going to yield what they’ve won, whether those victories were from trade treaties or from government policy. …

Source: ‘Changing The Flow: Water Movements in Latin America’, a report by Food and Water Watch, Red Vida, Transnational Institute, The RPR Network and Other Worlds. 2009.

By Martin Mowforth for the TVOD website.

Key words: FAO; Unicef; access to water; sanitation; agricultural demand for water; coronavirus.

In March (2021) the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations published a number of studies to mark World Water Day held on 22nd March each year since 1993. World Water Day celebrates water and raises awareness of the global water crisis. A core focus of the event is to support the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6: water and sanitation for all by 2030.

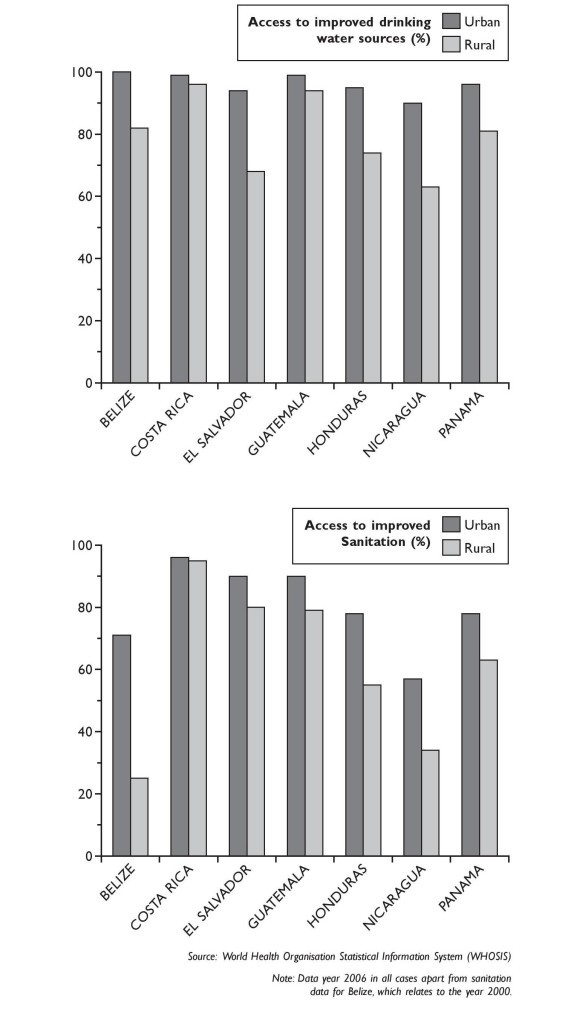

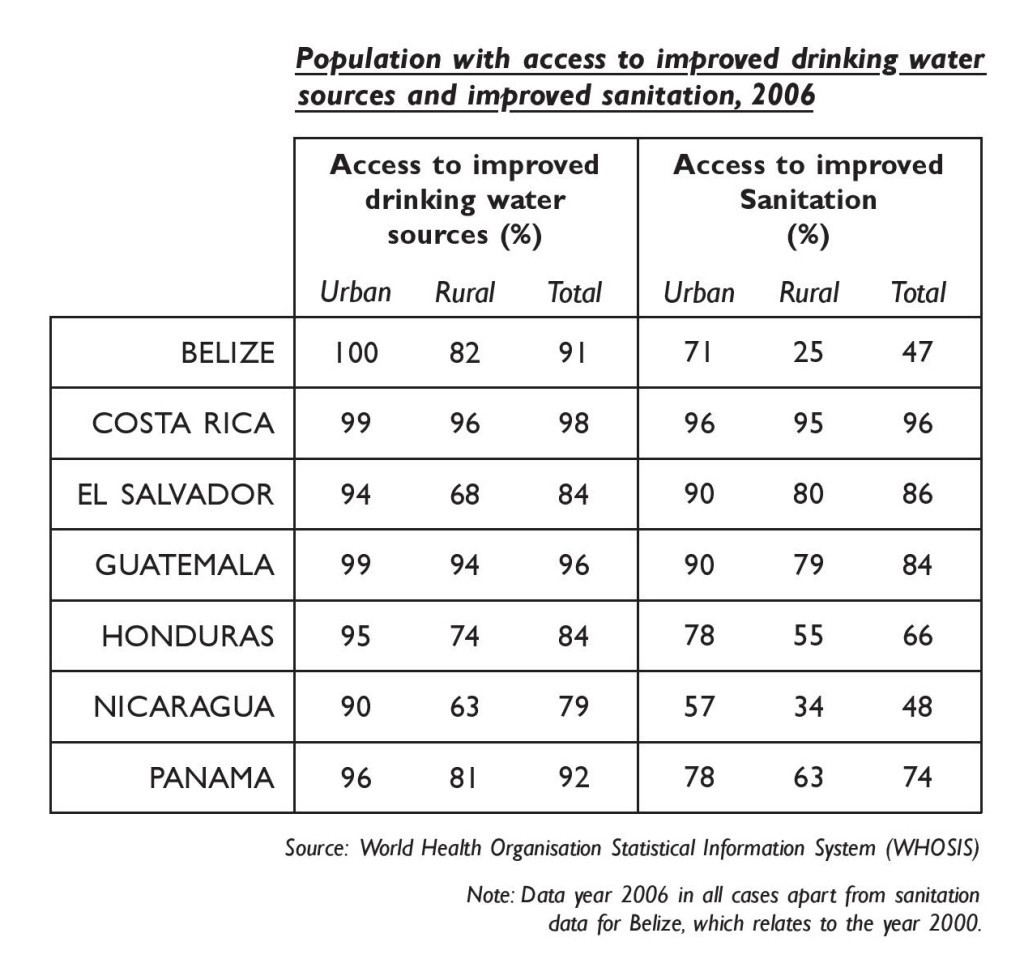

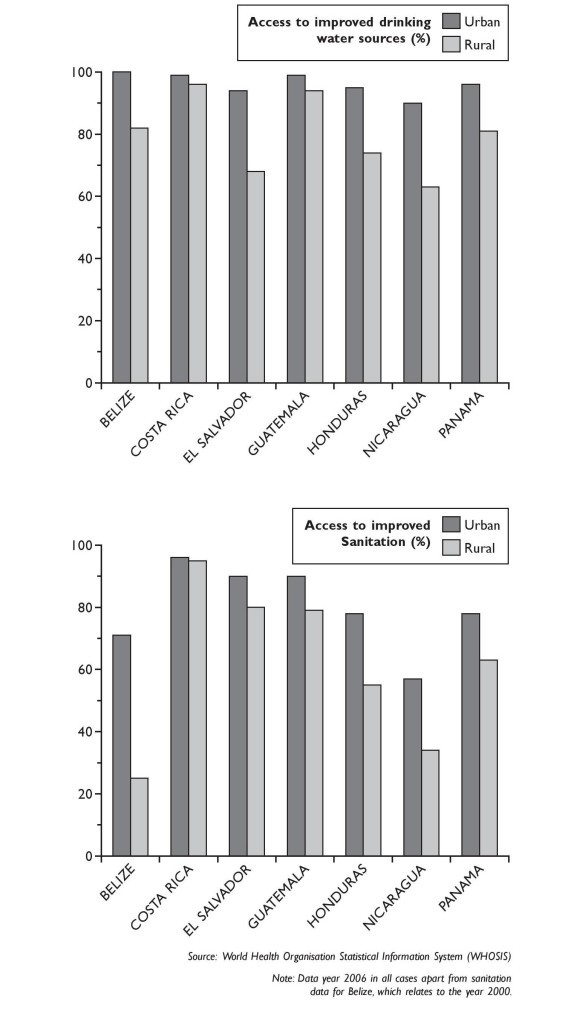

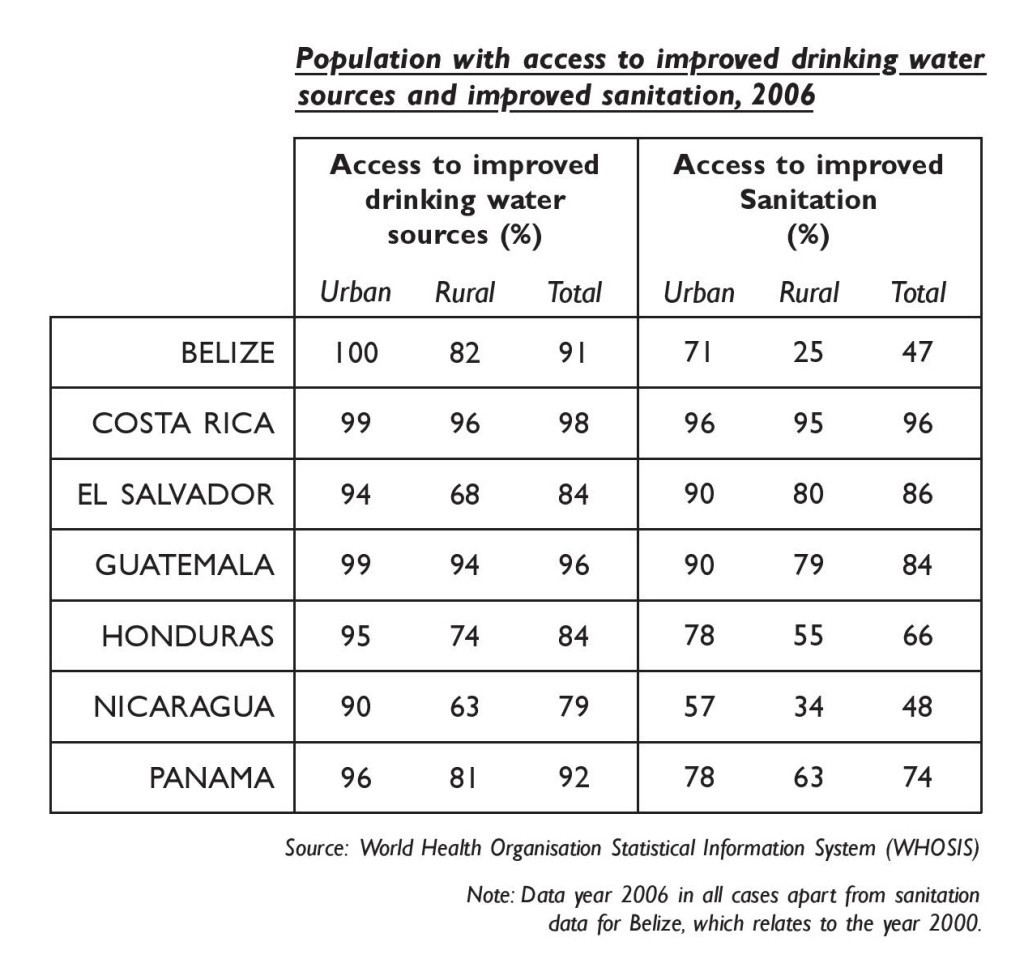

According to one study, access to water in Latin American countries has become more problematic and more urgent as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. The problems are felt more urgently in rural areas due to the lack of rains in some areas and the lack of public policies which guarantee safe access to safe water.

According to Tanja Lieuw of the FAO’s department of Climate Change and Environment in Latin America, “The pandemic has increased the urgent need to guarantee the right to water, the major public resource required to prevent illnesses and to contribute to economic recovery and sustainable development.” (El Economista, 22.03.21)

Agriculture uses 70 per cent of the total consumption of water and according to Julio Berdegué, a regional representative of Latin America for the FAO, a 50 per cent increase in agricultural production will be needed to meet the future demand of a growing population. That would require the extraction of 15 per cent more water than current levels of extraction. It will not be easy to balance that growing demand with the need to provide access to water for the 35 per cent of the Latin American and Caribbean population who do not currently have safe access and the even greater numbers who do not have sanitation services.

Berdegué suggested that one of the keys to modernising and improving access to water would be coordination between government ministries, local government departments and different sectors of the economy. In Central American countries, rural areas are often overlooked by different levels of government and their needs are unknown and/or ignored by specific sectors of the economy which tend to view social and infrastructural problems as not their business.

In a November 2020 report, UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund) warned of an impending sanitation crisis in Central America, made all the more severe by the effects of Hurricanes Eta and Iota. Unicef was particularly concerned about the existence of a great deal of stagnant standing water following the hurricanes which would enable the breeding and spread of more disease, including covid.

Sources:

UNICEF website: www.unicef.org

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) website: www.fao.org/land-water/events/world-water-day-2021/en/

El Economista, 20.12 20, ‘Unicef advierte de una crisis sanitaria por falta de agua en Centroamérica’.

El Economista, 22.03.21, ‘El acceso universal al agua en Latinoamérica es más urgente tras la pandemia, según la FAO’.

After a two year delay, the Nicaraguan Water and Sewer Company (ENACAL) signed contracts with seven Nicaraguan companies to start construction of 49 potable water systems and sewer systems in 27 Managua neighborhoods. The projects are estimated to benefit 130,000 citizens in the capital city and include potable water connections to 10,000 households and sewer connections to 18,000 households.

The project is being financed by a US$38 million credit extended by the Inter-American Development Bank. The project was scheduled to break ground in March 2009, but it suffered setbacks. The money will also go toward increasing the pumping capacity of wells in Managua, updating two sewer treatment plants, as well as toward sewage treatment improvements in Tipitapa and Ciudad Sandino. (La Prensa, Apr. 14)

Reproduced from Nicaragua News 20 April 2011

Report by: Nicaragua Dispatch

In celebration of World Water Day, the World Bank today announced a new $30 million project to bring potable water and sewage services to 85 rural municipalities in Nicaragua.

In celebration of World Water Day, the World Bank today announced a new $30 million project to bring potable water and sewage services to 85 rural municipalities in Nicaragua.

The sustainable water project, funded by $14.3 million in World Bank loans and $15.7 million in grants, will provide basic water and sewage service to 52,000 Nicaraguans over the next five years.

In Nicaragua, only 68% of the rural population has access to drinking water, and only 37% have access to sewage treatment, according to the World Bank. The government claims the percentage of those with access to drinking water in the urban households is slightly higher — around 84%. But in a country of daily water rationing in many poor neighborhoods, government statistics on access to drinking water are notoriously unreliable (in 2007, Ruth Selma Herrera, then-head of the state-owned Nicaraguan Water and Sewage Company, had to adjust the official statistics from 90% coverage to around 70% coverage after discovering just how inflated the government numbers were).

Maura Madriz Paladino, director of the water program for the Alexander von Humboldt Center, a non-governmental organization specializing in environmental issues, told The Nicaragua Dispatch last year that her organization surveyed Nicaraguan homes in 2011 and found that 80% of Nicaragua’s population doesn’t receive the quantity or quality of water it needs—a situation she qualified as “alarming.”

“We can’t determine who has access to drinking water by looking at the number of people who have plumbing in their homes, but in Managua a lone there are lots of homes that have pipes in the walls but no water in the pipes,” Madriz said. “We need to talk about the percentage of people who actually have potable water available to them in the quantity and quality to satisfy their basic needs.”

lone there are lots of homes that have pipes in the walls but no water in the pipes,” Madriz said. “We need to talk about the percentage of people who actually have potable water available to them in the quantity and quality to satisfy their basic needs.”

Says Herrera, the problem in Nicaragua is not the amount of water, but the quality.

“We are a country rich in contaminated water resources,” she said this morning in an interview on a local radio station Café con Voz.