May 07, 2019 | Pulitzer Centre

By Guido BILBAO

This is a short article produced as one of the Pulitzer Centre’s Shorthand Stories series. We are grateful to Guido Bilbao for permission to reproduce the article here. The article leads via a link in the final sentence to an excellent multimedia report which we encourage all our readers to visit for a very informative experience. The project which is the subject of this report was supported by the Pulitzer Centre on Crisis Reporting.

Key words: deforestation; Darién Gap; illegal logging; land ownership; indigenous peoples; mapping with drones.

Darién is a land full of challenges. First and foremost is the advance of loggers and settlers who threaten its tropical forests. Land ownership, constantly changing, has direct consequences on the health of the forest. That is why we embarked on a story that, through the indigenous people who organise to defend it, goes through the different forces that threaten their survival.

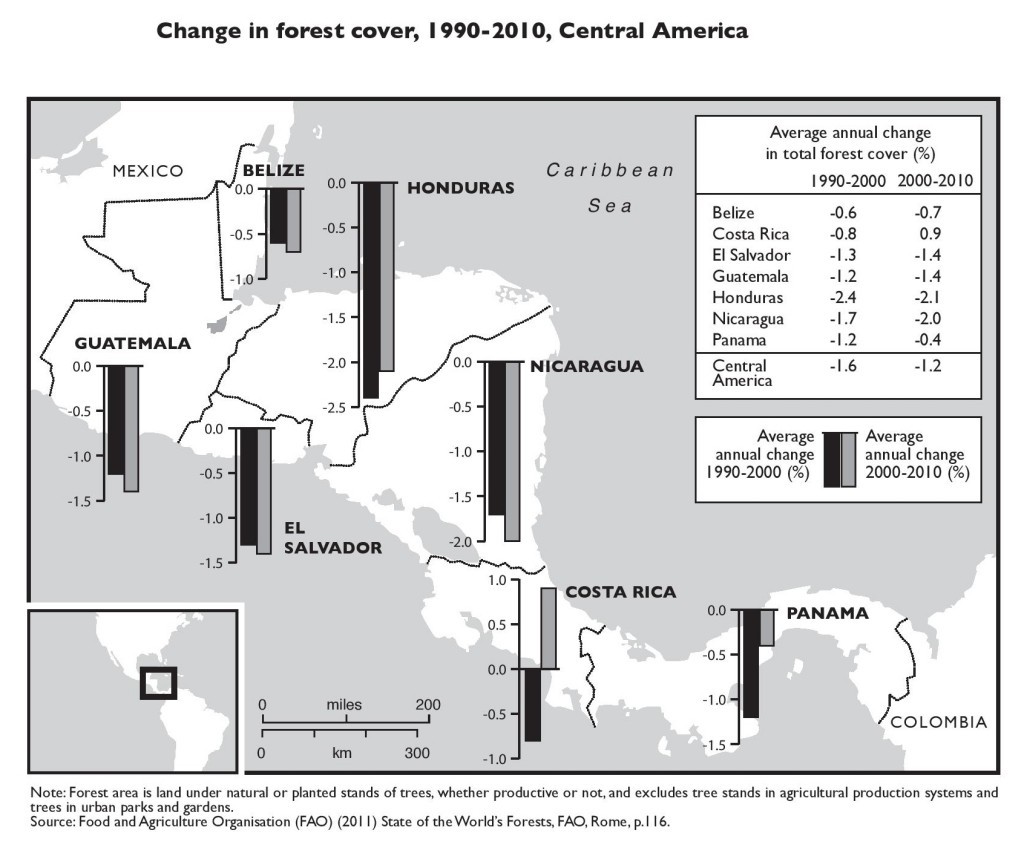

First we mapped the growing deforestation and declining forest cover that has evolved over the last 17 years. The result was overwhelming. Although we knew about the height of the felling, we did not imagine such a dramatic result. We were still prisoners of the general view of a forgotten place that always remains the same over time. Well, no. The effects reach the deepest areas of a forest that is the bridge of biodiversity between South America and Central America. Although here the Pan-American Highway is interrupted, the truth is that the opening of the Darién gap is in fact taking place.

The map shows us that the legalized indigenous territories have a more robust forest cover than the non-indigenous territories, or even protected areas. Then, we sought to define the areas in conflict, and we found that the dispute over untitled lands also defines how the tropical forest will be used. We worked together with the team of indigenous drone pilots and mappers to create a map of land ownership that shows how indigenous peoples with legalized territory are much more efficient than the central government and its system of protected areas to take care of the forest. We also defined the lands being claimed by communities that are inside national parks. We came to the determination that there are 650,000 hectares in dispute for which the Ministry of the Environment of Panama does not want to respond.

Once we defined the areas where deforestation was concentrated and where there were conflicts between settlers and indigenous peoples, we tried to explain how the logging business works. This is how we found the business around companies that use micro-titling of land in the name of poor peasants and then build enormous latifundios without having paid for those territories.

For the Panamanian government, deforestation is an improvement of the land. In this way the felling is rewarded. And businessmen take advantage of legal loopholes to advance over a territory where the presence of the Panamanian State is nil. Through exhaustive searches in the Public Registry, we discovered the titling of 2,000 hectares in indigenous territory that were carried out over two years in more than 40 different deeds. And with that land as collateral the businessmen got mortgages from state banks. To verify these payments we accessed the records of the Ministry of Agricultural Development where we found payments to these companies for $2 million over the past 10 years – more than 60 orders of payments for smaller sums that together build a small fortune.

However, we understood while doing the fieldwork that we did not want to continue abusing the myth of the cursed and wild land. Like a 21st-century Old West or a tropical Siberia, the myth of the wild Darién has grown since ancient times. But when visiting the communities and in spite of the threats of the settlers and the logging, despite the poverty and absence of the State, we found that there was a vitality and a work of great commitment to defend the forest and their cultural heritage. The historical narrative about Darien is full of tragedies and barbarities. But it is a story without heroes. And in these times of climate change and environmental apocalypse we wanted to highlight the work of all these communities that, against all odds, defend the tropical forest. Therefore, without losing sight of the weight of the investigation, we decided to change the focus to highlight the work of these defenders of Darién who risk their lives to try to prevent further deforestation, since they understand that the disappearance of the forest means the disappearance of their culture.

When setting up the transmedia project, we did it following the research process. We narrated the myth of the accursed Darién, explained the legal situation of the land, then the wood business and widespread corruption, to end up telling the story of the defenders of the Darién in a 10-minute mini-documentary.

We built a trailer to promote the transmedia project that you can navigate here in English and Spanish.

Guido Bilbao was born in Argentina where he majored in journalism. He has worked in his home country, Spain, and in Panamá where he has lived for 15 years. His writing has appeared in El País, Le Monde Diplomatique Berlín, La Prensa Panamá and La Nación Argentina. He has also directed documentaries for Al Jazeera International. His first documentary ‘Time to Love: A Backstage Tale’ was screened at the Lincoln Centre in March 2017.