Por Fabiola Pomareda García | pomaredafabiola@gmail.com

7 octubre, 2022, Semanario Universidad

Les estamos muy agradecido a Fabiola y al Semanario Universidad, un semanario tico, para su autorización para reproducir su artículo en el sitio web The Violence of Development. Además le estamos muy agradecido a Pamela Machado, una periodista Brasileña, para la traducción y el resumen del artículo de Fabiola específicamente para nuestro sitio web.

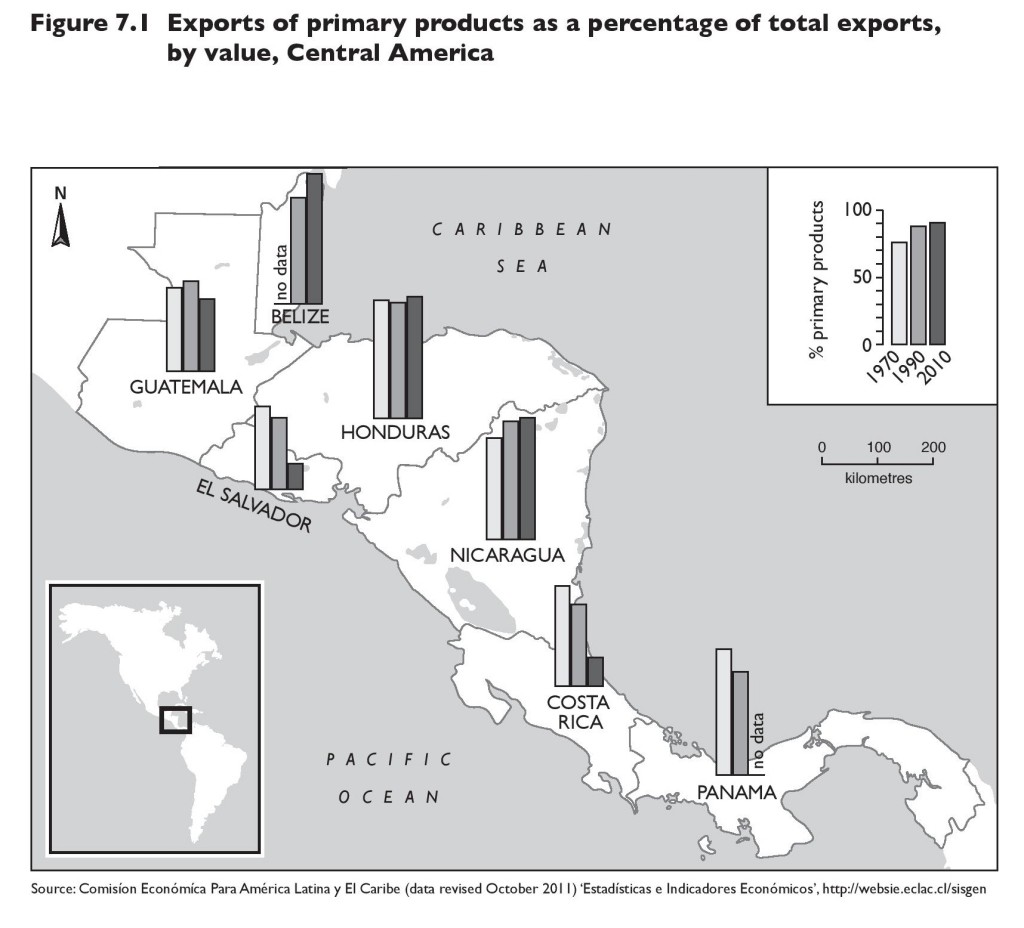

La investigación analizó cuáles han sido las implicaciones del CAFTA en la seguridad social, específicamente en lo que respecta al mercado de trabajo, los medicamentos y propiedad intelectual, la apertura del mercado de los seguros y la importación de alimentos.

Indicadores del mercado laboral de la última década desmienten la promesa hecha por la segunda administración de Óscar Arias Sánchez de que el Tratado de Libre Comercio con Estados Unidos generaría 500.000 empleos, según una investigación del politólogo Andrej Badilla Solano.

El investigador del Centro de Investigación en Cultura y Desarrollo (CICDE) de la Universidad Estatal a Distancia (UNED), expuso lo anterior en su conferencia “A 15 años del DR-CAFTA: Cómo el tratado de libre comercio con los Estados Unidos ha impactado a la seguridad social”.

Badilla señaló que el tratado tuvo consecuencias directas sobre la seguridad social en cuanto al mercado laboral y los medicamentos; así como consecuencias indirectas, como la segmentación médica producto de la apertura de mercado de seguros y la importación de alimentos.

Si bien actualmente un 42% de las exportaciones del país tienen como destino los Estados Unidos, según datos de 2022 de la Promotora de Comercio Exterior (Procomer), aquella promesa de generación de empleo de la segunda administración Óscar Arias Sánchez nunca se cumplió, afirmó Badilla.

Mostró los datos de cómo en el periodo entre el 2010 y el 2021 la tasa de desempleo ha oscilado alrededor del 10%, mientras el subempleo ha oscilado alrededor del 20% y la tasa de informalidad se ha mantenido en un 40%.

“Todo el periodo posterior a la implementación del tratado no ha habido variaciones en los datos sobre empleo. La estrategia implementada por el Estado ha sido la atracción de Zonas Francas, que están en un régimen de excepción y sus contribuciones se limitan al pago de cargas sociales bajo condiciones muy ventajosas. Pero la estrategia de generación de empleos a través de Zonas Francas resulta insuficiente para la demanda de empleo que tiene la población costarricense”, explicó Badilla.

Al 2018 la cantidad de empleos que generaban las Zonas Francas representaba solo el 5,3% del total de la fuerza de trabajo de Costa Rica (alrededor de 116.000 empleos), citó Badilla.

“Los indicadores muestran un marcado deterioro del mercado laboral durante esta década. Seguimos esperando los 500 mil empleos que nos prometió Arias Sánchez”, dijo.

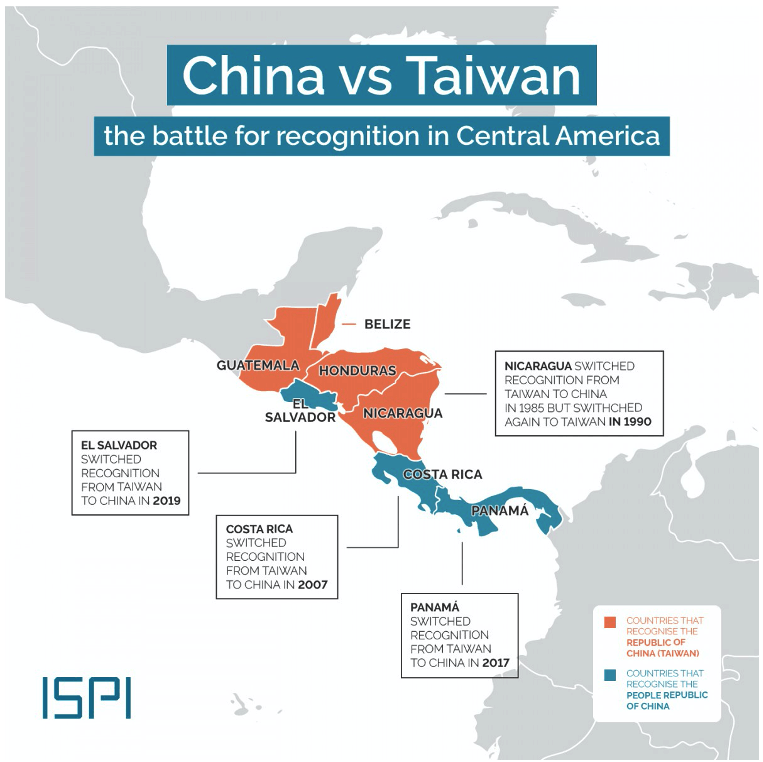

El Tratado de Libre Comercio entre Centroamérica y Estados Unidos (conocido como DR-CAFTA por sus siglas en inglés) fue ratificado por el país mediante el referéndum del 7 de octubre de 2007 y el tratado empezó a regir el 1 de enero de 2009.

Presupuesto para compra de medicamentos

En cuanto a los medicamentos y la propiedad intelectual, Badilla aclaró que Costa Rica pudo haber negociado mejores condiciones de propiedad intelectual, ya que el tratado generó un encarecimiento de los medicamentos debido a la protección de patentes y propiedad intelectual.

Según explicó, muchos de los medicamentos que se utilizaban en Costa Rica ya estaban protegidos por reglas de propiedad intelectual desde la segunda mitad de los noventas, ya que Costa Rica se unió a la Organización Mundial de Comercio (OMC) en 1995 y a la Organización Mundial de Propiedad Intelectual (OMPI) en 1999.

Con el tratado lo que hubo fue una ampliación de las medidas y una creación de condiciones aún más favorables para los dueños de las patentes, dijo. Esto tuvo un impacto en la seguridad social ya que los medicamentos que tiene protección de propiedad intelectual son muchísimo más caros que los genéricos. La situación tiene un efecto en el presupuesto asignado a la compra de medicamentos de la Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social (CCSS) destacó.

Badilla citó un estudio de Martínez Piva y Tripo (2019), que muestra que un 35% del presupuesto asignado a la compra de medicamentos de la Caja corresponde a medicamentos con protección de patentes.

“Como hay una lista de medicamentos oficiales y algunos tienen esta protección de propiedad intelectual, a la Caja no le queda más que pagarlos, no le queda más que pagar el precio que los productores determinen. Pero podríamos pagar menos y destinar menos del presupuesto si estos medicamentos fueran genéricos”, destacó Badilla.

Mayor acceso a «comida chatarra»

Otro señalamiento del investigador es que el aumento en la importación de productos agrícolas, tanto para la producción como para el consumo, permitió un acceso a una mayor variedad de alimentos con alto contenido calórico, lo cual generó cambios en la dieta y ha tenido un impacto en la salud de la población.

“Hay consecuencias como una mayor disponibilidad de comida chatarra, con efectos dañinos para la salud”, resaltó Badilla.

Citó que en todos los países de Centroamérica la prevalencia de obesidad en adultos oscilaba entre un 12% y un 15% antes de la firma del CAFTA. Pero después de la aprobación del tratado la prevalencia de obesidad aumentó en un 10%.

En Costa Rica la prevalencia de obesidad entre adultos era de un 14,8% en el año 2000; mientras que en el 2016 era de un 25,7%.

La obesidad está asociada a enfermedades crónicas como diabetes, hipertensión, problemas cardíacos y prevalencia de cáncer, entre otros, recordó Badilla.

El investigador del Centro de Investigación en Cultura y Desarrollo (CICDE) de la Universidad Estatal a Distancia (UNED) Andrej Badilla.