The following section also appears in the book under the same sub-heading, but the section which appears her is a much fuller version.

Eduardo Galeano’s classic work ‘Open Veins of Latin America’ explains how the imperialist states of Europe and the United States kept Latin American countries relatively free from the development of domestic industry by two particular means. First, a system of loans and interest-inflated repayments absorbed finance that would otherwise be available for domestic investment – the recent debt crisis is nothing new. Second, the development of a railway network, normally seen as a necessary condition for industrial development, was designed to link areas of primary production with ports (for export) rather than linking internal areas with one another: “thus railroads, so often hailed as forerunners of progress, were an impediment to the formation and development of an internal market.”[1]

To break out of what were seen as the chains of imperialist domination through which Central America had served simply as a supplier of primary produce to the industries of Europe and the USA, the strategy of domestic industrialisation was followed by some nations from the 1930s onwards. “These measures included increasing tariffs on imported goods. In Central America this was largely to help raise revenue, rather than promote import substitution.”[2] As British academic Victor Bulmer-Thomas admits, however, this industrial expansion did not amount to much. He cites five particular obstacles to industrial growth:

- energy supplies were woefully inadequate;

- virtually no credit was available;

- foreign exchange for essential capital equipment was hard to obtain;

- the market remained too small; and

- efforts at regional integration at this time came to nothing.[3]

The post-WWII development of the dependentistas or the Dependency School of thought associated the development of independent national industry with the notion of import substitution industrialisation (ISI). ISI was “an attempt to restructure the nature of economic relations with core economies [Europe and North America] … This would reduce dependence on imported goods, so helping the balance of payments, and would also provide employment.”[4]

Although dependency theory draws on the work of Marx, it is particularly associated with economic historian and sociologist André Gunder Frank[5], although his work simply became the most famous expression of what many had been thinking and saying around Latin America for some time. Dependency theory argues that western capitalist countries have grown as a result of the expropriation of surpluses from the Third World, especially because of the reliance of Third World countries on export-oriented industries (coffee, bananas, bauxite and so on) which are notoriously precarious in terms of world market prices. The theory uses the notion of core–periphery relationships to highlight the inequality, where the core is the locus of economic power within a global economy.

André Gunder Frank[6] takes matters one step further in his notion of the ‘development of underdevelopment’ which stresses that it is the underdevelopment of the structures in Third World countries created by First World capitalist development that creates dependency – see Cristóbal Kay[7] and Walter Rodney[8]. As anthropologist Arturo Escobar bluntly asserts, “Europe was feeding off its colonies in the nineteenth century, the First World today feeds off the Third World.”[9] In other words, dependency theorists see development of the core through exploitation of and extraction from the periphery, leaving the periphery in a constant state of underdevelopment.

Above all else, theories of dependency are in general agreement that the interdependence resulting from global economic expansion and the suppression of autonomous growth results in unequal and uneven development. The dependentistas explain Latin America’s failure to industrialise as a result of this unequal power relationship between the core (USA and Europe) and the periphery (Latin America, and of course Africa and parts of Asia).

Success in Central American ISI was rather limited for a number of reasons, chief amongst which were the small size of the Central American domestic markets, poor infrastructural development and the fact that many industrialisation efforts within the region produced similar products. Additionally, “although some consumer goods were relatively straightforward to produce, attempts to replace the import of other goods (particularly industrial machinery) highlighted the limits of ISI at that time.”[10]

In the 1970s, attempts to industrialise for the sake of independent development changed motivational tack as flows of international finance into the region became the major stimulus to limited industrial development. The debt crisis which followed “these vast flows of credit”[11] is well documented elsewhere[12] and seemed to represent a new form of dependency – ‘new’, but as noted above by Galeano, one that was already well-rehearsed in the nineteenth century.

In the late 1970s and particularly through the policies pursued by the Reagan-Thatcher axis of the early 1980s, Third World attempts at ISI were replaced by an export-oriented model of development, “building on ideas of free trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) as the way forward for indebted nations.”[13] The simplistic notion of comparative advantage was used to justify the need for Third World nations to produce goods or crops for which they have a natural advantage. This effectively justified the continuation of the colonial model of development, and the debt crisis served as a mechanism to ensure the continuation of a relationship of First World dominance over Third World nations.

The economic model mandated by the USA and Britain in the 1980s was later imposed on developing countries by the international financial institutions (IFIs) – the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and in Latin America the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The model advocated cuts in public spending and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, especially utilities such as energy companies.[14]

Free trade and economic growth are regarded as essential pre-requisites of development by the supranational and national agencies: the World Bank, IMF, World Trade Organisation (WTO), Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), European Union (EU) and G8 governments. The discourse of these agencies is commonly referred to as the Washington Consensus and its ideology of free trade is captured in the term neoliberalism. Free trade is synonymous with economic globalisation which is synonymous with the spread of capitalist relations of production, and whichever of these terms is employed, it amounts to an ideology.

Neoliberalism sees development as a single linear progression of economic growth and well‑being, a model that has been portrayed by a number of theorists as a series of steps or stages (such as Rostow’s The Stages of Economic Growth[15]) to the ‘promised land’ – a developed state. There is an almost universal acceptance, at least among those who hold power, that there can be no ‘development’ without economic growth and no economic growth without free trade, an equation that commands near universal respect but which development scholar Gilbert Rist and others insist needs to be questioned.[16]

The notion of free trade itself, however, manages to hide the uneven and unequal economic interdependencies manifest for example in trade protectionist measures adopted by First World governments. In this regard the hegemony of the United States of America is noteworthy, though equally the power vested in the WTO, the G8 and key trading agreements (especially the North American Free Trade Agreement and the Association Agreement with the EU) should not be underestimated.

Free trade fundamentally requires open and deregulated markets which supposedly provide a level playing field to those who operate business such that there exist no restrictions to trade. As the WTO explains, “In order to do business as effectively as possible, companies need level playing fields so that they can have equal access to natural resources, expertise, technologies and investment, both within countries and across borders.”[17] In theory this would allow national economies to specialise in producing goods or providing services that they are supposedly best at producing or providing. They would export these goods or services and import the things that they are not so good at producing. This is the notion of comparative advantage, one of the theoretical planks on which the ideology of free trade is built.

Comparative advantage is based on the theories developed by David Ricardo in the nineteenth century[18], but as Rist points out, “it assumes a number of hypothetical facts which rarely occur in reality”[19], and he proceeds to list thirteen of these assumptions. Activist and writer Teresa Hayter refers to the advice given to Third World governments as being based on the “apparently unimpeachable doctrines of comparative advantage, to the effect that they should concentrate on what they are supposed to be good at: the production of raw materials and primary commodities.”[20]

The theoretical level playing field belies the inequalities of development, economy and power which exist between and within the First World and the Third World. In the case of Latin American and Central American countries, Wooding and Moseley-Williams tell us that “before the current phase of globalisation, [this] was the region of the world where the greatest inequalities were found”, and that “today it is even more unequal.”[21]

Writer Fred Rosen is also critical of the theoretical framework of the Washington Consensus, arguing that it exists “at the height of abstraction, de-linked from reality”,[22] and Wayne Ellwood suggests that “talk of ‘level playing fields’ and ‘pure competition’ obscures the evidence that poor countries are severely disadvantaged to begin with”.[23] Oscar Guardiola-Rivera refers to this supposed playing field as being one “where players are unequal and competition unfair.”[24]

In the existing circumstances of inequality, it can be forcefully argued that there can be no such thing as free trade or a level playing field.

The deregulation of the local business environment – deregulation is another of the theoretical planks on which the ideology of free trade is built – to create the hypothetical level playing field actually creates the conditions which clearly favour those with access to wealth and resources. Stealing Bernard Crick’s phrase, we might describe deregulation as “the dramatic bonfire of the controls needed to make free markets tolerable”.[25] Without those controls which protect the national industries, those who stand to gain are those who already have the advantage of wealth and power that enable them to access even greater levels of capital and technology.

Elsewhere in the world beyond Central America, the idea of promoting a strategy of import substitution industry had been dealt a blow by the rise of the South-East Asian ‘tiger’ economies, and after the 1970s few nations in the world clung onto or placed great hope in achieving development through the rise of an economy led by national industrial growth. For those nations which did not willingly embrace neoliberalism, it was forced upon them by the USA and Europe and by the debt crisis. The crisis was and still is managed by the world’s two major international financial institutions (the IMF and the World Bank) in which the interests of the two major political centres (the USA and Europe) hold sway.

The debt crisis was managed through structural adjustment programmes which later metamorphosed into Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), although the PR part of the initials might have more accurately signified ‘Public Relations’. Through these the international financial institutions imposed on indebted nations loan conditions which included trade liberalisation, the deregulation of industry and the privatisation of state-owned industries and services. This is what Martin Khor (Director of the Third World Network) describes as the ‘de-industrialisation’ of the developing world[26], preventing governments from managing their country’s basic services such as health, education and water and from protecting the livelihoods of small producers and manufacturers by placing tariffs on unfairly subsidised imports.

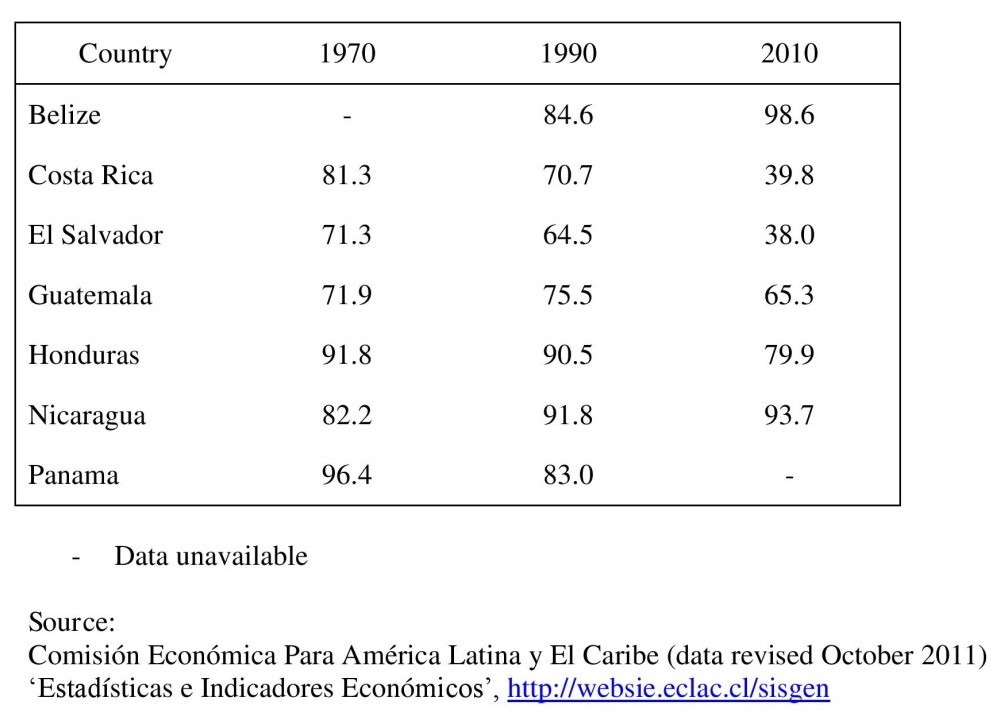

But how does this process of de-industrialisation fit with the evidence of increasing manufacturing importance in national statistics for the Central American economies? The Table on Exports of manufactured goods as a percentage of total exports demonstrates that from 1970 to 2010 the value of the export of manufactured goods as a percentage of all exports increased in five of the seven countries. The answer to the apparent contradiction is found in the maquilas or sweatshop assembly factories which have been established in the region over the decades since the 1970s. As labour costs increased in the developed capitalist or metropolitan nations, transnational corporations (TNCs) found it profitable to re-locate the most labour-intensive elements of their production to low-wage countries which would serve simply as a platform to receive components which were altered in some way and then ‘sprung off’ the platform either to markets in the metropolitan nations or to other platforms elsewhere in the world where further alterations or additions were made to the product.

The maquila process is one which contributes to a globalised economy rather than to a national economy. Very often there is little advantage accruing to the host nation other than the employment opportunities offered to local populations, but the maquilas are associated with extremely poor wage levels and abusive conditions of employment. The development of maquilas is covered again in more depth later in this chapter.

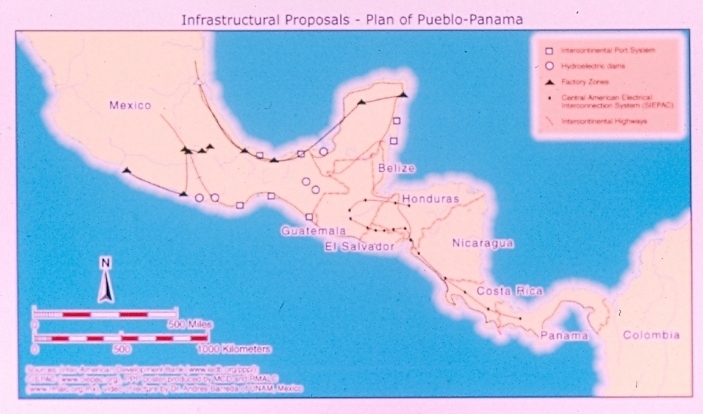

To some extent this inequality of access to modern business infrastructure is illustrated by the example of the Plan Puebla-Panama given in the following section. This brings us very suitably to ask the question: how have the effects of these global policies shown themselves in the economies of Central America? And that in turn brings us to an examination of the most recent twenty years of free trade treaties negotiated between the Central American nations and other trading blocks.

[1] Eduardo Galeano (1973) Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, New York and London: Monthly Review Press, p. 218.

[2] Katie Willis (2002) ‘Open for business: strategies for economic diversification’, in Challenges and Change in Middle America, edited by Cathy McIlwaine and Katie Willis, Essex: Pearson Education.

[3] Victor Bulmer-Thomas (1987) The Political Economy of Central America Since 1920, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.80-81.

[4] Op.cit. Katie Willis..

[5] André Gunder Frank (1967) Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America, Monthly Review Press, London.

[6] Frank, A. G. (1966) ‘The development of underdevelopment’, Monthly Review 18, 4: 17–31; (1969) Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution, New York: Monthly Review Press; (1970) Lumpen-Bourgeoisie: Lumpen-Development, Dependency, Class, and Politics in Latin America, New York and London: Monthly Review Press.

[7] Kay, C. (1989) Latin America Theories of Development and Underdevelopment, London: Routledge.

[8] Walter Rodney (1988) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, London: Bogle L’Ouverture Publications.

[9] Arturo Escobar (1995) Encountering Development, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p.83.

[10] Op.cit. (Willis).

[11] Ron Ayres and David Clark (1998) ‘Capitalism, Industrialisation and Development in Latin America: the Dependency Paradigm Revisited’, Capital & Class, 64 (Spring) (pp.89-118), London. (Quote from p.110).

[12] For example, see: Duncan Green (2003) Silent Revolution: the rise and crisis of market economics in Latin America, Latin America Bureau; Susan George (1988) A Fate Worse Than Debt, Penguin; Susan George (1992) The Debt Boomerang, Pluto Press; and refer to the work of the World Development Movement and the Third World Network.

[13] Op.cit. (Willis).

[14] John Perry (2008) ‘The debate on energy and climate change – a different perspective’, Ch. 17 (pp 229-244) of ‘Opening Doors – Improving housing services for refugees and new migrants’, Chartered Institute of Housing.

[15] Rostow, W. (1960) The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-communist Manifesto, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[16] Gilbert Rist (1997) History of Development, London: Zed Books.

[17] WTO/OMT (1995) GATS and Tourism, Madrid: WTO/OMT, p. 1.

[18] David Ricardo (1817) The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, London, J.M. Dent, 1973.

[19] Op.cit. (Rist, p.114).

[20] Teresa Hayter (1982) The Creation of World Poverty: An Alternative View to the Brandt Report, London: Pluto Press, p.96.

[21] Bridget Wooding and Richard Moseley-Williams (2004) ‘Worlds Apart’, Interact, Spring 2004. London: Catholic Institute for International Relations, p. 9.

[22] Fred Rosen (2003) ‘Changing the terms of the debate: a report from Antigua’, NACLA Report on the Americas, XXXVII (3), November/December 2003, page 25. New York: North American Congress on Latin America.

[23] Wayne Ellwood (2004) ‘The World Trading System’, New Internationalist, no. 374, December 2004, Oxford: New Internationalist.

[24] Oscar Guardiola-Rivera (2010) What if Latin America Ruled the World? How the South Will Take the North into the 22nd Century, London: Bloomsbury, p.3.

[25] Bernard Crick (2004) ‘How the rich stole the dream’, The Independent, London, 11 June 2004. Crick was referring to the manipulation of the capitalist tax system to benefit the rich, but in the context of the development of the capitalist economic system. We consider that the contexts of his remark and of ours are similar enough for it to be used to describe deregulation.

[26] Martin Khor (21 June 2006) ‘Beware of NAMA’s slippery slope to de-industrialisation’, TWN Info Service on WTO and Trade Issues (June 06/18), www.twnside.org.sg/title2/twninfo431.htm (accessed 30.07.12).

While the Euro zone plunges into meltdown and the governor of the Bank of England predicts the worst crisis in the UK since the depression, innovative new ideas based on relationships of solidarity between countries are being successfully put into practice in the countries of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (ALBA).

While the Euro zone plunges into meltdown and the governor of the Bank of England predicts the worst crisis in the UK since the depression, innovative new ideas based on relationships of solidarity between countries are being successfully put into practice in the countries of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (ALBA). I think ALBA is going to provide an alternative for us in the western world. From what I can see we are pretty lost, we haven’t really got any ideas of where we are going. It can’t be about bailing out bankers and their bonuses. So for me, ALBA really does provide that framework.’

I think ALBA is going to provide an alternative for us in the western world. From what I can see we are pretty lost, we haven’t really got any ideas of where we are going. It can’t be about bailing out bankers and their bonuses. So for me, ALBA really does provide that framework.’