By Amy Porter

July 2017

This article was written especially for the newsletter of the Environmental Network for Central America (ENCA) and appears in ENCA 70 (July 2017).

Amy Porter has worked as Amnesty International UK’s Country Coordinator for Guatemala and recently with two NGOs in rural Guatemala. She has spent much time

accompanying the La Puya Peaceful Resistence.

Key words: gold mining; Guatemala; peaceful resistance; Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI); female human rights defenders; police violence; arsenic in water.

On 5 March 2017, members of the Guatemalan community-led, anti-mining movement, Resistencia Pacífica La Puya (Peaceful Resistance of La Puya), celebrated five years of maintaining a 24-hour blockade at the entrance of the Progreso VII Derivada gold mine. The mine is operated by EXMINGUA, a subsidiary of the US-based company, Kappes Cassiday & Associates.

While extractive projects in Guatemala are as controversial as ever within the communities they affect, companies have complained of a moratorium on new licences. The number of licences granted has dropped drastically, from 51 new licences in 2007 (33 for exploration and 18 for extraction), to just five in 2015 (3 for exploration and 2 for extraction).[1] Although discussed by government, a moratorium was never officially adopted, and the current Morales administration declared its opposition to such a measure.[2]

In a report published in January 2017, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) noted that there are currently 24 licences in place for exploration in Guatemala, and 274 for extraction, for mining, oil and natural gas projects. [3] The report mentions only once, in passing, the issue of indigenous community resistance to extractive projects, and blames the industry’s limited contribution to Guatemalan GDP for the lack of new licences.

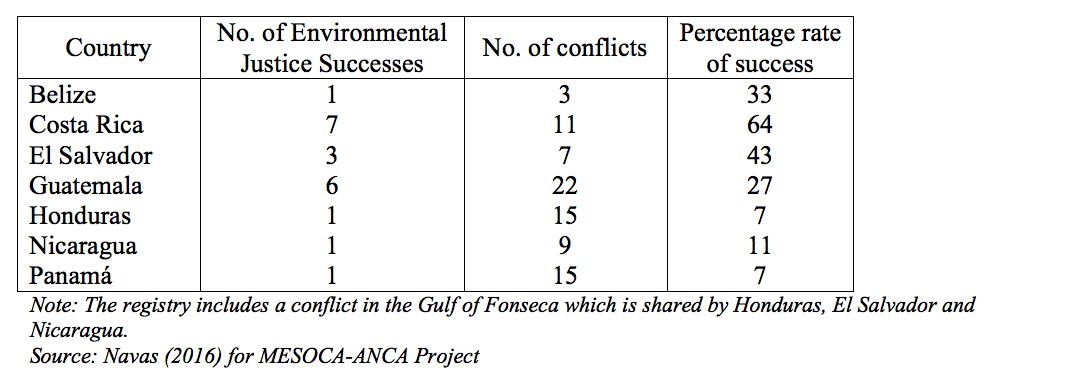

Founded in 2002, the EITI is facing a crisis of legitimacy, having failed to lend sufficient weight to social and environmental issues.[4] Otto Haroldo Cu, president of the Observatorio Nacional de Transparencia (National Observatory for Transparency) and an advisory member of the EITI, stated in 2015: “the fact that extractives count for less than 2% of the country’s GDP should make us stop and think … 78% of municipalities with active mining licences registered were engaged in some kind of conflict in 2010. Is this an adequate trade-off? Is this the kind of development that we want for our country?”[5]

The EXMINGUA website boasts that the La Puya mine has brought “development, growth, jobs, progress and wellbeing for hundreds of families residing in San Pedro Ayampuc and San José del Golfo, the bordering municipalities”. [6] Members of the communities, however, feel differently. Responding to the lack of information offered by the local or national authorities, or the mining companies themselves, they established a peaceful blockade in 2012.

The movement’s five-year milestone is an opportunity to celebrate their achievements; in 2016, a judicial order brought mining at the site to a temporary halt. It is still in effect. However, it is also a stark reminder of the long and costly struggles that rural communities in Guatemala face to gain control over issues on which they have a legal right to be consulted. Members of the La Puya resistance are determined to maintain their blockade until the mine is closed, for good.

Many of the key activists who have kept the La Puya blockade running are women. Female human rights defenders face particularly great risks of intimidation, threats and harassment. Between 2012-2014, 1,688 attacks on female human rights defenders were reported in Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico.[7] In June 2012, Yolanda Oquelí, an activist at the La Puya site, survived a shooting. No-one has been arrested for the attack.

On 5 March, the 5-year celebrations at La Puya got underway with a protest march to the mine led by local youth. Cries of “Sí a la vida, no a la minería!” (Yes to life, no to mining!) rang out along the route. Over 300 people joined the day’s celebrations, which included a community lunch, running races, and speeches.

It was against this backdrop of community spirit and fierce resilience that ENCA member, Amy Porter, spoke with Felisa Muralles and Marta Catalán, two of the many women who have formed the backbone of the La Puya Peaceful Resistance movement. Muralles is from the community of San Pedro Ayampuc, and Catalán from San José del Golfo, the two villages which border the mine site. They reiterated their determination to see the mine closed, and shared how the peaceful resistance has been a source of both unison and division within the communities.

What was the objective of setting up the La Puya Peaceful Resistance movement?

FM: The intention was not to let the mining companies work here. We are fighting to get them off this land.

MC: The resistance started on 2 March 2012. For a short time, we had known that they wanted to put a mine here, close to the communities, and that’s when we started the protest site – because they hadn’t informed us about anything. And today we’re here celebrating 5 years. We were motivated to defend the water and the environment for future generations.

Were you surprised when you found out there was going to be a mine?

FM: In 2011, we didn’t know what it was going to be. There was no consultation, no information; they said it would be other things, never a mine. … They said they had bought the land to cultivate: pineapple, papaya, fruits. They started to build roads in and we still didn’t know it was going to be a mine. Until a group got organised and asked the Ministry [of Energy and Mines] whether there was a licence for extraction here, and finally they gave the information that yes, there was an authorised project here.

What do you feel you have achieved in the last 5 years?

FM: First, we’ve raised awareness with a lot of people, to recognise that mining is truly bad; we’ve shown them the proof. And we have learned how to better look after nature, the trees, the water.

MC: I think we’re the only resistance movement at the national level … which hasn’t had any deaths. We had some injuries when the [police] crackdowns happened, and we have had people get prison sentences. We have united to help each other. In the most difficult times, there’s always somebody at your side.

What have been the biggest obstacles?

FM: There have been so many obstacles. We’ve been victims of much criticism, and of police violence against us … they’ve used excessive violence to try to displace us. But they didn’t manage.

MC: At first … the mining company saw all the people here, and seeing all the women, they said that we had come here to prostitute ourselves, that we had abandoned our children, that we neglected them. A lot of things like that … They put around names of people, once they even put my Dad’s name, saying that he was seeing another woman; but of course he wasn’t, it was just to try and discredit the resistance movement. It didn’t stop us.

Has the gold that has been extracted here benefitted the local people?

FM: Hardly at all, because the royalties are only 1%. For every Quetzal* that they give, 50 cents go to the central government and 50 go to the local authorities. Last year, they paid royalties of Q305,000 ($42,000 USD) for the entire year … In 2014, they only reported from September to December, and they only gave Q6,000 ($818) to the municipality for everything they extracted. The benefits for the communities are minimal, there’s just contamination, destruction and problems … even families fighting amongst themselves. They say this is development, that’s its improvement, but that’s completely false.

[* Guatemalan currency]

Is the community very worried about the water contamination?

MC: Yes, we’re very worried … The levels of arsenic are naturally high here, but in 2015 when [the mine] was working a lot, the levels increased greatly, from 0.052 milligrams to 0.099 milligrams per litre of water … The Ministry of Health accept that this is because of the [mining] works, and asked [the local authorities] to do something. Supposedly, in San José del Golfo they put in filters, but the contamination levels haven’t decreased.[8]

FM: The municipal authorities, at least in San Pedro Ayampuc have not done anything, they say they don’t have money. So, the authorities got sanctioned … then they pay the fine with money that belongs to the town … and we’re still drinking contaminated water.

I noticed that there’s a water park close by, up there on the hill?

MC: Yes, it’s the strangest thing … there’s always water up there. In my house, we have water every 48 hours. When there’s water, we have to fill up a lot of containers … It shouldn’t be like this. When these companies come, they use millions of litres of water and don’t pay for it; we pay to be given water when they want us to have it. This water is ours [it’s not for] companies who come to contaminate and destroy.

Could you tell me about the family divisions?

MC: There are many divisions between parents and children, brothers and sisters … even in mine, I have an aunt who doesn’t speak to me … because as the municipal authorities see us in a bad light, and one of her daughters works there, it bothers her and we don’t speak.

What do you want from the Guatemalan government?

FM: What we want is for them to remove the mining projects, that they stop testing for more projects, and that [the companies] go back to their own countries and destroy them, and let us in Guatemala live here in peace.

MC: Really, I don’t expect anything, but what we would like most … is that they would think about the harm it’s doing, and please not give out any more licences.

What types of alternative development would you like to see?

MC: I would like to see sources of employment come from within the community. Because we know … how to care for Mother Earth, which gives us food. I dream of a Guatemala without mines, monocultures or transnationals.

FM: Better development would perhaps be training us how to look after the land, cultivate organically, and make irrigation systems. That would be good development for these communities.

Do you feel that international solidarity is helpful?

MC: Yes, because we’re not the only people feeling this way, there are others outside of Guatemala. If it was only in Guatemala, I think the government would always do what they wanted. So when people from abroad come to know what is happening here, the government distances itself from these things. For us, it’s very helpful that people from outside come and take away the information.

FM: Yes, it helps a lot, because I understand that when people come here they take away the message and publicise it, so the companies see that we are not alone, that yes, [people] in other countries very far away have their eyes fixed on Guatemala, on our struggles. I think this helps a lot to raise awareness, and it spreads the news of what’s happening here.

[1] EITI, 30 December 2016, Informe EITI Guatemala, 2014-2015

[2] Central America Data, 9 February 2016, Good News for Mining Sector in Guatemala [accessed 17.05.2017]

[3] EITI, 30 December 2016, Informe EITI Guatemala, 2014-2015

[4] Oxfam, 23 February 2016, Oil, gas and mining transparency initiative facing crisis of relevance and legitimacy

[5] EITI, 17 July 2015, Falling extractives revenues in Guatemala amidst political turmoil [accessed 17.05.2017]

[6] http://exmingua.com/exmingua/corporativo/inversion-y-desarrollo/ [accessed 20.05.2017]

[7] http://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Deadly_shade_of_green_English_Aug2016.pdf [accessed 20.05.2017]

[8] According to the World Health Organisation, the maximum permissible level of arsenic in water should be 0.010 milligrams per litre.