Category: Panama

Panama Supreme Court declares mining contract illegal

In the November/December 2023 additions to The Violence of Development website, Martin Mowforth reported on protests and blockades in Panama that brought the country to a standstill. Here he reports again on developments in this ‘people versus the government’ conflict.

By Martin Mowforth

February 2024

Key words: mining protests; road blocks; First Quantum Minerals; Minera Panama (formerly Minera Petaquilla.

On 28 November 2023, the Supreme Court of Panama declared that a renewal contract that allowed a Canadian mining company (First Quantum Minerals) to continue operating Central America’s largest open pit copper mine was “unconstitutional”.

For over a month before the Supreme Court judgement, the renewal of the contract had given rise to massive protests that spread throughout the country causing blockages on major highways that impeded the passage of national and international trade. According to the EFE News Agency, the blockages had caused losses in the order of millions of dollars and shortages of various goods in cities. Newspaper articles frequently talked of the country being brought to a standstill, as the previous entry into this section of The Violence of Development website records.

Groups taking part in the protests included Indigenous peoples, trade unionists, schoolteachers, students, and environmentalists.

The concession rights for the Cobre Panama project were obtained in 1997 under Law 9 by Minera Petaquilla, now known as Minera Panama SA, according to First Quantum. Minera Panama is a majority owned subsidiary of First Quantum. The court indicated in its decision that Panama’s National Assembly accepted a contract that didn’t follow the correct legal process and therefore contravened the constitution.

Environmentalist Raisa Banfield declared the judgement as “a victory for popular democracy”, and Ombudsman Eduardo Leblanc asserted that “democracy worked”. He also noted that after dividing the country, it was now necessary “to move towards recovery and reconciliation”.

Following the judgement, protestors began to remove the blockades on major highways.

First Quantum Minerals has notified the government of Panama that it intends to present arbitration claims, under a free trade agreement between Panama and Canada. Once again, then, claims made by transnational corporations to arbitration courts such as the World Bank’s International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) demonstrate their inherent injustice through their attempts to prevent countries and communities making decisions and taking action against the despoliation of their environments and societies.

Sources:

- AFP, 28 November 2023, ‘Panama Court Nixes Major Mining Deal’.

- Ariadne Eljuri, 29 November 2023, ‘Panama Supreme Court Declares Mining Contract Illegal’, Orinoco Tribune.

- The reader is also referred to the numerous sources cited in the previous article in this section of the website.

Panamanian workers are being punished for anti-mining protests

Chapter 5 of TVOD website carries numerous articles about the Petaquilla mine in Panama, including news of the Supreme Court’s declaration of the mining contract as illegal. This declaration brought to an end the demonstrations and road blockages called to protest the renewal of the contract that allowed a Canadian mining company (First Quantum Minerals) to continue operating a large open pit copper mine. Pablo Meriguet’s article below covers one aspect of the aftermath of the protests and mining cessation. We are very grateful to Pablo and to People’s Dispatch for their permission to reproduce the article here.

People’s Dispatch website: https://peoplesdispatch.org/

By Pablo Meriguet, People’s Dispatch

June 23, 2024

Key words: Mining; National Union Of Workers Of Construction And Similar Industries (SUNTRACS); Panama; Retaliation; Saúl Mendez; Unions; Worker Rights And Jobs.

Panama’s Largest Union, SUNTRACS, Has Denounced That Several Of Their Bank Accounts Were Frozen As A Retaliatory Measure For Opposing A Mining Concession.

Panamanian business groups and large transnational capital are trying to take revenge on the National Union of Workers of Construction and Similar Industries (SUNTRACS), says Saúl Méndez, general secretary of the union. For several months, the state-owned company Caja de Ahorros has frozen 18 bank accounts of the union, one of the largest in the country, which represents more than 25,000 people. According to government sources, the closure of the bank accounts is due to alleged links of SUNTRACS with terrorist activities.

However, according to Méndez, the freezing of their accounts is an act of retaliation by national and international economic groups that have economic interests in Panama, for being the political group that led the protests against open-pit metal mining during October and November of last year.

Last year, SUNTRACS led dozens of popular organisations that sought, through massive street protests, to defend the country’s sovereignty and environmental well-being by opposing Law 406. The law promised privileges for more than 20 years to First Quantum Minerals (FMQ), with the possibility of extending those privileges for an additional 20 years. The demonstrations resulted in the Supreme Court of Justice declaring Law 406 unconstitutional on November 28, 2023. A few hours later, President Laurentino Cortizo announced that the copper mine “offered” to FMQ would be closed.

These types of neo-colonial economic measures, which aim to cede national sovereignty for long periods, have already been applied on several occasions in Panama, probably the most infamous being the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty (or Convention of the Canal through the Isthmus). With this treaty, Panama ceded its sovereignty to the United States, which thus appropriated one of the most important commercial points in the world: the Panama Canal. In this way, the protests of 2023 join a long struggle of the Panamanian people against the economic and political impositions of the national and transnational oligarchic groups that promote this type of neocolonial activities.

Faced with the freezing of its bank accounts, SUNTRACS called a 24-hour strike on June 20. Road closures were reported in several cities by the mobilized workers, who demanded the restitution of “the workers’ funds”. During the demonstration, slogans such as “Here the crime was to fight for the dignity of the people” were heard. In addition, the strike managed to paralyze a good part of the construction industry.

In addition, Méndez assured that SUNTRACS filed a formal complaint for the freezing of its bank accounts before the International Labor Organisation and the Superintendency of Banks. He also assured that, despite these types of measures that seek to neutralize them, SUNTRACS will continue to denounce and mobilize in favour of the interests of the Panamanian people.

The Petaquilla Mine, Panama, and opposition to it

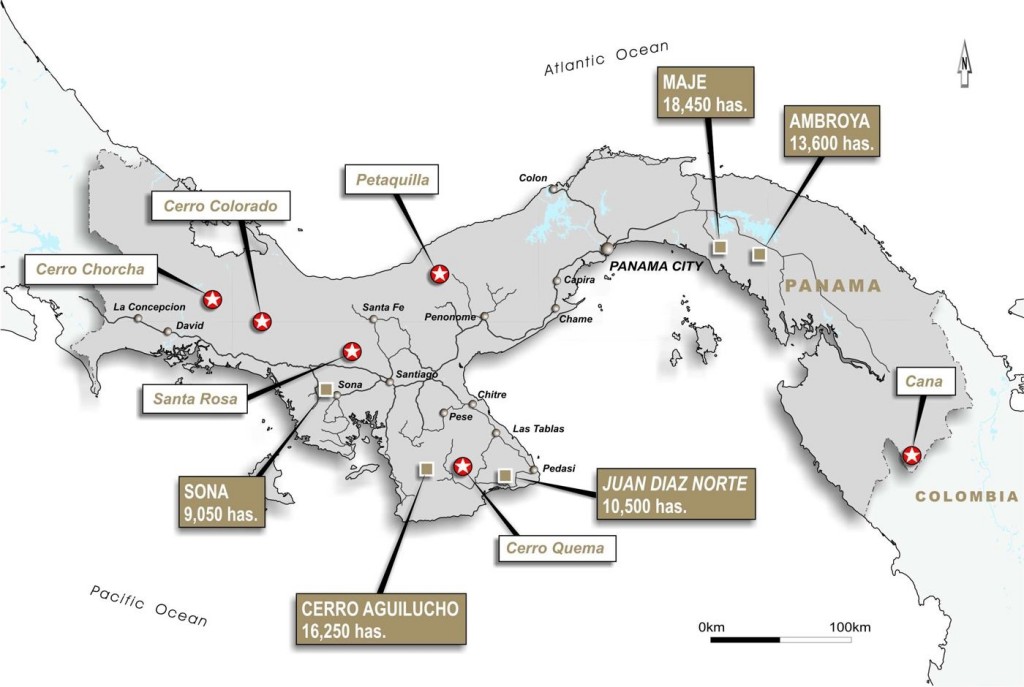

The controversial Petaquilla mining concession is located in the Donoso district in the north-central provinces of Coclé and Colón, covering an area of 13,600 hectares.

In 1997 the Panamanian government granted a concession for gold and copper mining to the company Minera Petaquilla, S.A. Two separate mining projects are being developed with Panamanian and Canadian investment – an open-pit gold mine, and one of the largest open-pit copper mines in the world.

The fierce opposition to the Petaquilla mining project from civil society groups and local communities stands in stark contrast to the company’s declarations of self-praise – see Below. The benefits in terms of a limited number of low-paid jobs seem scant, when compared to the environmental costs, including the contamination of their water supply, and the loss of land and forest cover. The anti-mining movement in Panama has been gaining momentum and there have been numerous protests against the Petaquilla mines. Protests in May 2009 blocked access to both mines for two weeks.

Conservationists point to the devastating and irreversible environmental impacts on the region, which is part of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor. Concerns include the building of access roads in a remote area of high biodiversity, destruction of primary forest, and siltation and pollution of rivers.

In August 2008, the NGO Sustainable Harvest International declined funding from Petaquilla Copper Ltd to undertake sustainable development programs with communities in the region. The proposed collaboration was deemed irreconcilable with their commitment to conservation. Their president Florence Reed stated:

Even if Petaquilla were truly committed to full mitigation and remediation, this mining venture will result in a legacy of environmental and social disruption because of the immense area that will be deforested and the number of local indigenous communities that will be displaced.[1]

Sources:

MiningWatch Canada, November 2008, ‘Important information about the Petaquilla mining project in Panama’, http://www.miningwatch.ca/updir/Petaquilla_background.pdf (Accessed 5 August 2009).

MiningWatch Canada, January 2009, ‘Panamanian rainforest communities threatened by mining’, http://www.miningwatch.ca/index.php?/Panama/Petaquilla_alert (Accessed 5 August 2009).

[1] Sustainable Harvest International, August 2008 http://www.sustainableharvest.org/PR82008.cfm (accessed 5 August 2009)

Petaquilla Minerals’ own version of its mining operations

According to Petaquilla Minerals, the Canadian company undertaking the gold extraction, “the Petaquilla mine, the biggest gold-mining project in Central America, has proven, in less than a year of social work, to be the most successful model of sustainable mining in existence”.[1] The corporate social responsibility (CSR) page of its website describes its social programmes as main production modules which serve as:

mechanisms to foster community productivity by promoting a more varied economy and sustainability. This is achieved by assisting people with ventures that will provide for a livelihood beyond subsistence farming, identifying more effective and efficient manners of production, and transferring the use of new technology.[2]

It should be noted that, apart from these very few small-scale programmes, the CSR page of the company’s website says nothing of the many other aspects of responsibility – pollution, pollution clear-up, forced evictions, land clearances, deforestation, the lack of compensation payments, and more.

At the crux of the purportedly ‘sustainable’ mining model is the notion of social and environmental compensation. Another of Petaquilla Minerals’ websites states “we are committed to being aware of the environmental impact the working of a mine can cause, but above all we are sufficiently capable of counteracting this impact with our actions”[3] Underlying this notion of sustainability is the acknowledgment that the mining will cause significant damage, and thus counterbalancing measures must be taken to enable the project to pass necessary government legislation and to gain support of the local communities. Such measures include reforestation, development of infrastructure, and education and social projects.

[1] Gold Exploration in Panama, Petaquilla Minerals Ltd, www.goldexplorationinpanama.com/mineria.htm (accessed 5 August 2009)

[2] www.petaquilla.com/petaquilla_corp_soc_res.aspx?IdCsr=3 (Accessed 14 December 2010)

[3] Desarrollo Petaquilla, Petaquilla Minerals Ltd, www.desarrollopetaquilla.com/mineria%20sostenible%2001%20ingles.htm (accessed 5 August 2009)

Presidential approval of mining damage

The following extracts are taken from: Eric Jackson (13 December 2008) ‘ANAM approves Petaquilla gold mine, people downstream are flooded out’, The Panama News, www.thepanamanews.com/pn/v_14/issue_23/economy_05.html

On November 26, about a dozen families in Nueva Lucha de Petaquilla, a Ngobe village down the Petaquilla River from Richard Fifer’s Molejon strip mine, were coping as best they could, on their own since the village was flooded out three days over when the Petaquilla River overflowed its banks. These people moved into harm’s way when men from Richard Fifer’s Petaquilla Minerals came and burned their old houses on higher ground, and help became more remote when this same company destroyed the roads and trails of traditional access to the riverside village and put up a gate to exclude environmentalists, reporters and Liberation Theology religious folks from a vast section of northern Cocle and western Colon provinces.

When Nueva Lucha was flooded, the community sent Merardo Morales and Martín Rodríguez out on foot to summon help. Two days later, after fording several dangerously swollen streams, Morales reached Coclesito and Rodríguez arrived at La Pintada.

There would be no presidential visits, there was no Panamanian government request for US military help … President Torrijos has for years, even when Fifer was a fugitive from embezzlement charges, even when Fifer was openly defying the nation’s environmental laws, supported Fifer’s gold mine project. …

Meanwhile in Panama City, as the people of Nueva Lucha awaited help, … and a week after the National Environmental Authority (ANAM) had fined Fifer’s Petaquilla Gold $1 million for starting the Molejon gold mine without an environmental permit and assessed it $934,694 in damages for the deforestation caused by its road and strip mine site, ANAM director Ligia Castro had a political statement to make. She approved an environmental permit for the gold mine. …

The permit granted by ANAM’s acceptance of Petaquilla Gold’s environmental impact statement requires the company to post two bonds, in the amount of $14,374,000 to cover future environmental damage. It doesn’t appear that driving people in western Colon province from their homes, either directly by sending in goons to burn their houses or slightly less directly by ruining water supplies or fisheries upon which they depend or by increasing the risk of flooding by destroying the ability of ecosystems to retain water, are among the damages that the Torrijos administration would have the company cover.