by ZACH DYER, November 26, 2014

This story was originally published in The Tico Times. It is reproduced here by kind permission of The Tico Times. http://www.ticotimes.net/2014/11/26/nicaraguan-coffee-farmers-seek-creative-solutions-to-drought-climate-change

Key words: Coffee cultivation; coffee rust (roya); climate change; waste water management; river pollution

MATAGALPA, Nicaragua – Coffee drinkers in the United States reach for a warm cup of joe when the crisp autumn wind blows in November, but meanwhile, farmers in Nicaragua are looking at their coffee trees with trepidation.

The coffee harvest in Central America started in November but many farmers here have little to do. Drought ravaged much of Central America — especially Nicaragua, Guatemala and Honduras — earlier this year, and farmers are feeling its impact now. Fields that should be full of coffee pickers are empty. Mills that should be guzzling red coffee cherries by the basketful sit with their tanks nearly empty. Many farmers say the harvest could be four weeks late, at least.

A view of the upgraded wet mill at La Hermandad Cooperative in San Ramón, Matagalpa, Nicaragua, on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2014. (Zach Dyer/The Tico Times)

A late harvest doesn’t necessarily augur a small harvest, but it does mean farmers who rely on coffee as their main income will have to stretch their budgets for another month after several years of slim earnings. This year’s drought, attributed to the El Niño weather phenomenon, is the latest hurdle for Central American coffee farmers who have seen their crop yield dwindle because of the devastating leaf rust fungus known as roya.

Francisco Blandon, a coffee farmer in the steep green hills outside Yali, Jinotega, said that two years ago he noticed the rains were no longer reliable. “It was dry when it should’ve been wet, and wet when it was supposed to be dry,” he said. Blandon said that a lack of rainfall and lingering damage from roya cut his harvest by 70 percent, to 53 60-kilogram bags of green coffee during the 2013/2014 season, compared to 184 bags in a normal year.

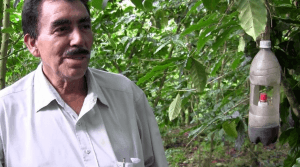

Francisco Blandon balances the pH of coffee wastewater on his farm in Jinotega, Nicaragua, on Nov. 20, 2014. (Zach Dyer/The Tico Times)

Blandon isn’t alone in his assessment. Drought and increasingly unpredictable rain cycles are among the symptoms of climate change that scientists say are making coffee a risky investment for farmers on the isthmus. Amid these conditions, farmers and other stakeholders in the coffee business have begun to look for ways to reduce the caffeinated crop’s environmental impact with a special eye on water management. A series of pilot projects in Nicaragua funded by the Dutch government and the sustainable certification label UTZ Certified have seen positive results in reducing water consumption, treating wastewater and providing farmers with a clean burning fuel as a by-product. Coffee is Nicaragua’s most valuable agricultural export and employs thousands in the poor Central American country. Changing the way farmers process their coffee for market could have a significant impact on the quality of life and environment in many coffee-growing communities here.

Effluent from El Carmen wet mill before treatment in Diriamba, Nicaragua. The wastewater has an average pH of 4, the same as acid rain. (Zach Dyer/The Tico Times)

Regardless if the coffee is organic or not, wastewater from coffee processing plants has been cited as a major source of river pollution in Latin America. The red fruit must be cleaned off the coffee in a process called de-pulping before the beans ferment, dry and are milled for export. Traditional de-pulping wet mills use large amounts of freshwater to transport the fruit though various stages of the milling and fermentation process. After de-pulping, the water is a brown frothy sludge. Coffee wastewater has a typical pH of 4 — the same as acid rain— compared to a neutral pH of 7 for pure water, as defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Farmers and processing plants would traditionally dump their coffee wastewater straight into streams without any treatment. The organic matter in the effluent encourages bacterial growth that pulls oxygen out of streams and lakes, suffocating fish and other marine life. A report from the Guatemalan Instituto Centroamericano de Investigación y Tecnología Industrial estimated that the processing of 547,000 tons of coffee during a six-month period in 1988 created the water pollution equivalent of the raw sewage from a city of four million people.

Blandon said that people downstream of his coffee farm would complain of stomach pains and irritated skin after drinking or bathing with water from the stream during the harvest.

Rigoberto Mendoza, another farmer outside Yali, has been farming coffee for 30 years. “Before, I didn’t understand the impact I was having on other people. I was harming them and others were harming me,” Duartes said, wearing a cowboy hat as he looked downhill from his farm.

Both Blandon and Mendoza were selected among the first 19 UTZ pilot programmes here that started rolling out in Nicaragua in 2010. Water savings are achieved by recycling water up to three times through the mill before the discharge is sent to a septic tank where the large solids are filtered out and the remaining fluid passes on to a bio-digester. There, the effluent mixes with manure and bacteria breaks down the organic matter from the coffee, producing methane gas that is captured and stored for use later. Filters in the digester isolate the physical waste from the water, which can be sent to a retention pond after lyme and other bases are added to it to reduce its acidity. At this point, the wastewater’s pH and organic concentration levels are safe enough to release back into the environment.

Before and after: Coffee wastewater prior to treatment, left, and once it’s safe to release back into the environment, right, at El Carmen laboratory in Diriamba, Nicaragua. (Zach Dyer/The Tico Times)

Small farmers benefit from these programmes, but they also have application for large commercial wet mills. In the Pacific town of Diriamba, CISA Exportadora — the largest exporter of coffee in Nicaragua, accounting for 30 percent of the country’s annual crop — has reduced its water consumption by 70 percent at the El Carmen wet mill, according to Tito Sequiera, vice general manager in Nicaragua for Mercon, the mill’s owner. CISA has the largest wet mill in Nicaragua and processes some 2,300 metric tons of green coffee, consuming up to 3,000 litres of water daily, depending on the volume of coffee processed. Before, CISA used 1,500 litres of water to process 256 kg of coffee fruit; now, the wet mill has reduced its water usage to 400 litres to process the same amount of coffee. Besides using less water, El Carmen’s water management system reduced contamination in the effluent by 80 percent.

“I’m from this area. For me, this project lifted a weight off my conscience because before I knew we were polluting,” said Gilberto Monterrey, chief of operations for the CISA wet mill. Monterrey said that CISA used to receive complaints from the community about the effluent’s vinegar-like smell. “You’d smell it in the homes and when it rained, the [retention] ponds would overflow. With this project, all that stopped,” he said.

(I am also grateful to Zach Dyer for his permission to use his article in The Violence of Development website, as well as to The Tico Times. Amongst all the negative news of violence from the region of Central America, it is pleasing to be able to report on developments that have a beneficial effect on both people and the environment.)