Key words: coffee cultivation; pesticides; endosulfan; Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs); Coffee Berry Borer beetle (CBB); Pesticide Action Network (PAN); field hygiene.

ENCA member Stephanie Williamson, who works for Pesticide Action Network (PAN) UK reports on farmers’ successful experiences from Central America

Endosulfan is a highly hazardous and persistent insecticide responsible for many poisoning incidents, including fatalities, in developing countries and for harm to wildlife. The PAN network has campaigned for over a decade for it to be banned. A massive step forward was achieved in 2011 when international policy makers added endosulfan to the list of pesticides on the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), for global phase out. While over 50 countries have now banned it, farmers in the coffee and cotton sectors continue to use it in some parts of the world, including several Latin American countries.

To find out how these farmers can shift to safer alternatives, PAN UK worked with the coffee sector to interview farmers certified under standards such as Fairtrade, organic, and Rainforest Alliance. These standards have prohibited farmers from using endosulfan for 3 or more years, so certified farmers have developed good experience in managing the key pest, Coffee Berry Borer beetle (CBB), by other methods. We interviewed 22 farmers in Colombia, Nicaragua and El Salvador, from small and medium family farms and large estates, to learn what methods they use and how they had made these changes.

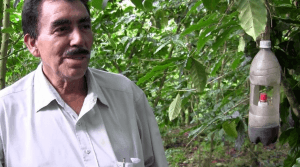

Don Abelino Escobar, Farm Manager, Belmont estate, Santa Tecla, El Salvador with one of his home-made traps, showing the methanol:ethanol dispenser. Credit: P Lievens, PAN UK

In El Salvador, several estates are now using traps baited with a mix of methanol and ethanol to attract the female adult borers when they start to emerge from fallen berries at the start of the rainy season. This method has been developed by the national coffee research institute PROCAFE and promoted to farmers by COEX export company. By trapping large numbers of female beetles and preventing them from breeding, pest levels in the developing coffee berries can be much reduced.

Don Abelino, farm manager for Belmont estate in Santa Tecla (El Salvador), a zone where CBB levels can often be high, recounted how he formerly applied endosulfan twice a year in plots which needed control. While endosulfan could be very effective, if it rained shortly after application, he would need to spray again, at further cost. At other times, an application would simply fail to control the pest and levels would rise, requiring yet more spraying. Since COEX agronomists introduced him to trapping as an alternative, he has been delighted with the results, stopped all endosulfan use and succeeded in gaining Rainforest certification for the estate. Furthermore, he no longer risks his workers suffering ill health from pesticide poisoning and is not contaminating the environment with powerful chemicals. Don Abelino’s experience is that trapping is very easy, very cheap and very effective. Approximate costs per hectare for trapping are US$12, compared with US$70 for two endosulfan spraying rounds.

In Nicaragua, Fairtrade co-operatives have introduced the traps too, with very good results for their members. They are also promoting use of biological pesticides based on a strain of the naturally occurring fungus Beauveria bassiana, which infects and kills CBB without affecting other insects. Organic farmers have found using the fungus extremely useful in their situation. The Miraflor Union of Cooperatives in Estelí has a small Beauveria production unit and sells the product to its members, along with training farmers in how to handle and use it effectively, given that it is a living organism and not a chemical.

All farmers we met are also doing field hygiene as the backbone of good CBB management. These include sanitary picking of bored berries or early maturing berries and collecting fallen berries and dried berries left on trees after the main picking season. These practices are essential to reduce the amount of pest breeding sites and reduce CBB levels in the following season. Farmers explained that the labour cost of these sanitary collections should be seen as an investment in achieving good quality coffee.

Our findings show that it is perfectly possible to achieve good CBB control without using endosulfan, across a range of farm sizes, climate zones and altitudes, pest pressure levels, and coffee production systems. We’ve also shown that methods which avoid pesticide use can be similar in cost, or sometimes cheaper. More governments need to take action to ban endosulfan in their countries, so that safer alternatives can be given a fairer chance.

You can watch four YouTube videos (in English and Spanish) of farmers telling their experiences via www.pan-uk.org/projects/growing-coffee-without-endosulfan

This work was kindly funded by the Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the Sustainable Coffee Programme powered by IDH and the ISEAL Alliance of sustainability standards.

In Central America, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica have still not banned endosulfan.