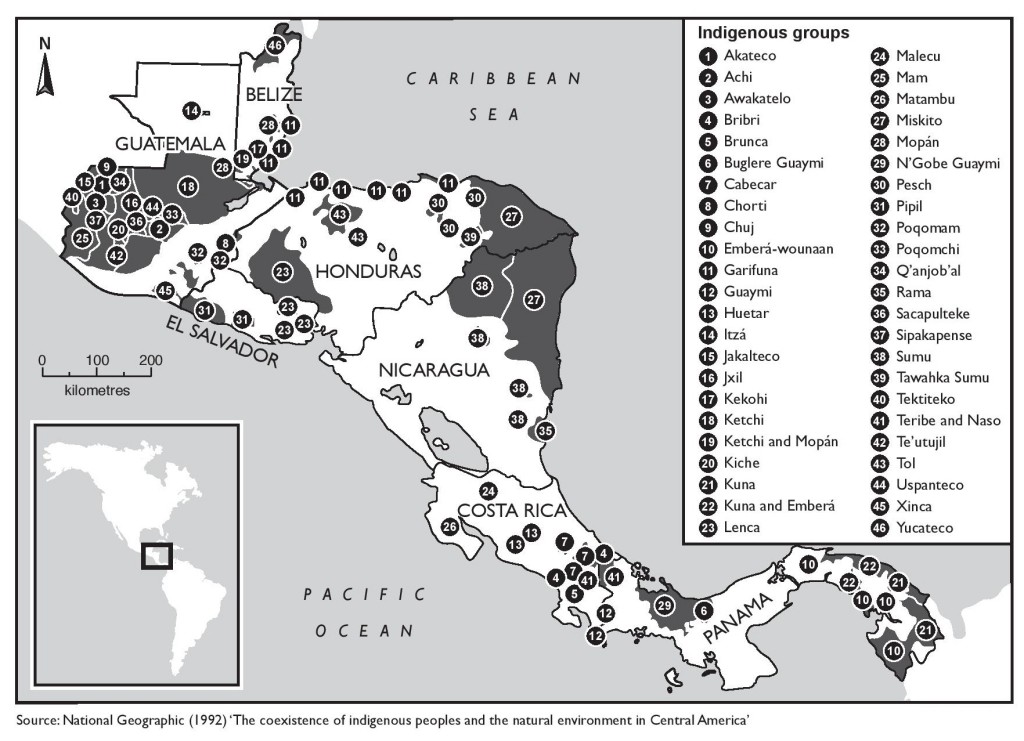

This figure is referred to in the book as Figure 8.1 (Page 154)

Category: Indigenous territories in Central America

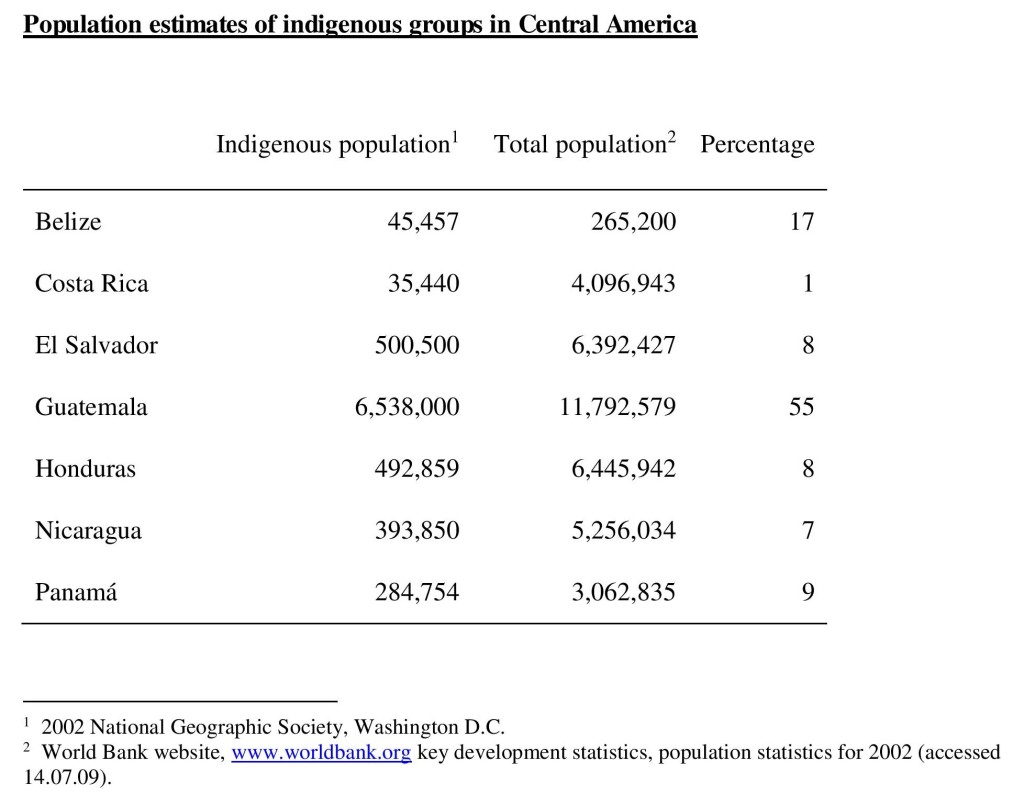

Population estimates of indigenous groups in Central America

This figure is referred to in the book as Table 8.1 (Page 153)

National indigenous populations, Central America

Notes taken from the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII): Desk Reviews of select MDG Reports as per Indigenous Issues: No. 2, 2007

http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/MDGRs_2007.pdf

Costa Rica

CR has an indigenous population of 68,000 people (2% of the national population), comprising eight peoples that live on 24 territories: the Bri bri, Cabécare, Brunca, Ngöbe Buglé, Teribe, Maléku, Huetáre and Chorotega. Most of Costa Rica’s indigenous peoples live in rural communities in the south of the country. While Costa Rica’s legal framework on indigenous issues is quite strong, the practical application of laws and international conventions that Costa Rica has ratified (including ILO Convention 169) has been lacking in force. Costa Rica’s indigenous peoples are reportedly still subject to insecurity over their lands and are largely excluded from social and economic development.

El Salvador

There are three indigenous peoples in El Salvador, the Nahua/Pipil, Lenca and Cacaopera. Although there is no reliable population data on indigenous peoples in El Salvador, it is estimated that they make up 10-12% of El Salvador’s population of approximately 6.4 million. El Salvador’s indigenous peoples mostly live in rural communities and are disproportionately affected by poverty. There is very little in the way of targeted government policies for the development of indigenous peoples. Indigenous languages in El Salvador, with the exception of Nahuat have largely disappeared.

Honduras

There are seven indigenous peoples currently living in Honduras, the Garífuna, Tolupán, Pech, Misquito, Lenca, Tawahka, and Chortí. According to Honduras’ most recent census, carried out in 2001, there are 427,943 indigenous people in Honduras, making up approximately 7% of the country’s population.

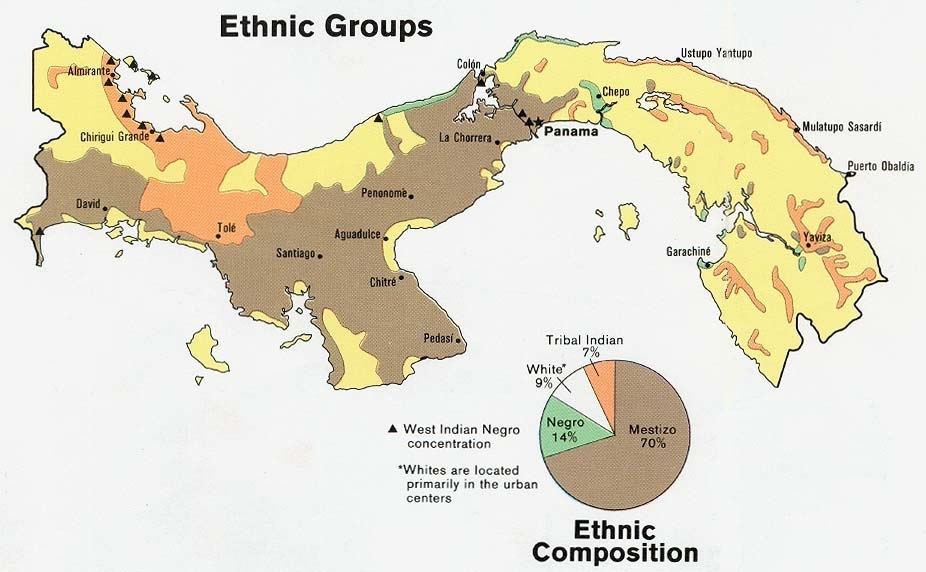

Panama

Panama has an indigenous population of 285,231 people, making up approximately 10% of the country’s population.17 There are eight indigenous peoples in Panama, the Ngöbé, Buglé, Bri Bri, Naso, Kuna, Emberá and Wounaan. Panama has five indigenous comarcas, or regions, which have some degree of autonomy from the central government. Despite having achieved considerable inroads in terms of the recognition of their lands, indigenous peoples in Panama continue to be excluded from socio-economic development and display alarmingly high poverty levels.

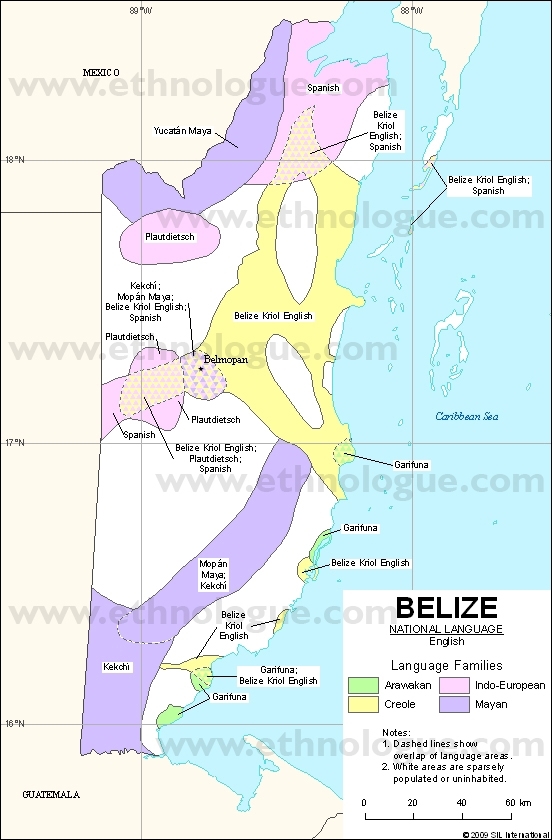

Belize

Has an approximate population of 279.5 thousand people; of these an estimated 6% are from the Garifuna indigenous group while approximately 10% are from the Mopan Mayan or Ketchi Mayan indigenous groups.17 While the Maya are mainly rural dwellers, the Garifuna live primarily in the urban areas.18 Thus their problems are specific to their dwelling circumstances whereby the Maya peoples’ primary issue surrounds land rights and the Garifuna are concerned with increasingly crime-ridden, diseased, por neighborhoods.19 As yet, neither of these two indigenous peoples is recognized in the Belizean constitution, because most Belizeans disregard the special and historic needs of the indigenous peoples.20 Significantly, however, is that all three of these peoples were mentioned in the introductory context of the MDGR for Belize. Also within the context of the introduction, the MDGR purports that poverty in Belize disproportionately affects rural populations and within these rural populations the indigenous Mayan people suffer inordinately high poverty statistics.

Costa Rica’s indigenous peoples

Bribri

The Bribri are the largest indigenous tribe in Costa Rica, comprising 35 per cent of the total indigenous population. The 2000 census stated that there were almost 10,000 indigenous Bribris, situated mainly in the Southern Pacific and Southern Atlantic zones on either side of the Cordillera de Talamanca in Costa Rica.[1] The Bribri have managed to conserve their native language in both written and spoken forms.

Cabécare

The Cabécare are the second largest indigenous group, making up 25 per cent of the indigenous population. The Cabécare have close ties with the Bribri group, as both sets of native lands lie in the Cordillera de Talamanca region in the province of Limón.

Brunca

The Brunca group live in the south of Costa Rica in the province of Puntarenas and represent 15 per cent of the total indigenous population. They closely follow their ancestral traditions, and are well-known for their Fiesta de los Diablitos in December, for which they craft intricate masks.

Guaymí

In the 1960s many of the Guaymí – or Ngöbe Buglé as they are known in Panamá – emigrated from Panamá to Costa Rica to settle. They now comprise 13 per cent of Costa Rica’s indigenous population.

Chorotega

The Chorotegas make up only 4 per cent of Costa Rica’s indigenous population. Although they no longer speak their native language, their ethnic identity and culture remains. Unlike many of the other groups, the Chorotega live in the northwest of Costa Rica, in the Nicoya province.

Huétare

Only a small community of the Huétare group remain in the San José province, representing only 3 per cent of Costa Rica’s indigenous people. Their native language and much of their cultural identity has been lost, although certain traditions such as the Fiesta del Maíz still remain.

Maléku

Although the Maléku only represent 3 per cent of the native population in Costa Rica, they still have their own language which is taught in local schools alongside Spanish. The Maléku are one of the groups with the least land property, and much of their reserve in the northern Alajuela province is inhabited by non-indigenous people.

Teribe

The Teribe are a small native tribe originally from Panamá, where they are also known as the Naso. They only comprise 3 per cent of the total indigenous population in Costa Rica; however they are much more prominent in Panamá. As with the Maléku, much of the Teribe’s territory is occupied by non-natives, which has resulted in a mixing of the indigenous and non-indigenous population.

[1] Carla Jara Murillo and Alí García Segura (2008) ‘Materiales y Ejercicios para el Curso de Bribri’, Universidad de Costa Rica, http://www.inil.ucr.ac.cr/cvjara-bribri1/cvjara-bribri1-introduccion.pdf (Accessed 24/09/2010)

Belize’s national languages

Used by permission, © SIL, (2009)

Costa Rica’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

National languages of El Salvador and Honduras

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Guatemala’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Nicaragua’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Panama’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Panama’s ethnic groups

Map of all languages, Central America

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.