Levi Gahman, Shelda-Jane Smith, and Filiberto Penados

December 15, 2020

We are grateful to the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) for permission to reproduce this article on The Violence of Development website. NACLA Report on the Americas is a progressive magazine covering Latin America and its relationship with the United States – nacla.org More details on the authors, to whom we are also very grateful, are given at the end of the article. The original article can be found at: https://nacla.org/news/2020/12/13/maya-land-fpic-belize

Even after the Maya’s watershed 2015 Caribbean Court of Justice land rights victory, the Government of Belize continues to condone land grabs in Indigenous territory.

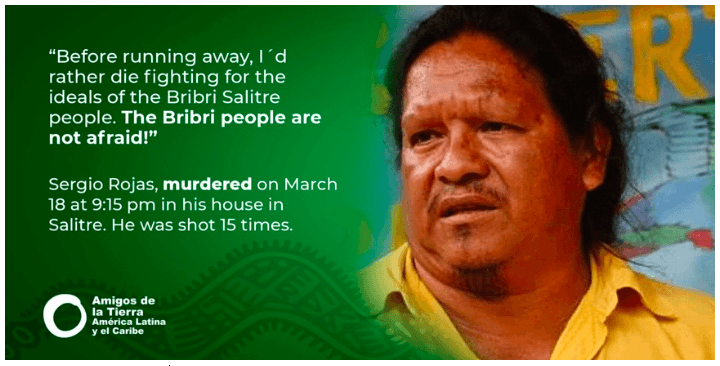

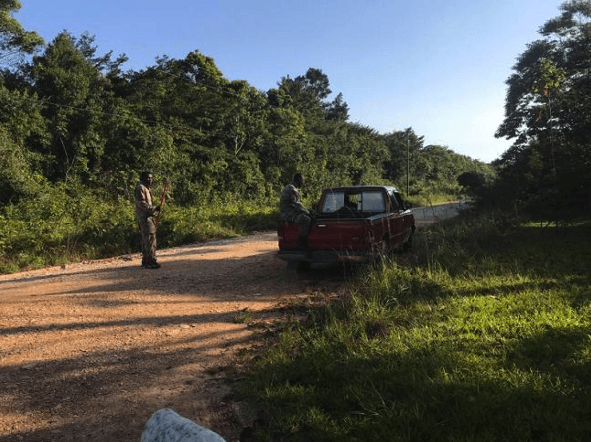

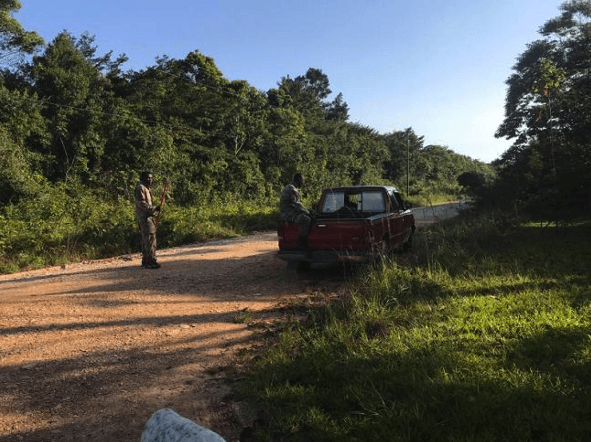

Survey workers in an unmarked vehicle place survey pegs without FPIC near Laguna, Belize. (Julian Cho Society)

Maya villages in Toledo District, Belize reported that during October [2020] speculators illegally opened survey lines in an attempted land grab. The lines were established without Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), cut through forests and corn and cacao fields, and the living spaces and homes of Maya families. The survey activity was reported in a press release issued by the Maya Leaders Alliance (MLA) and Toledo Alcaldes Association (TAA).

State-sanctioned FPIC violations against Qʼeqchiʼ and Mopan Maya communities have been going on for decades. But these most recent encroachments call into question the Government of Belize (GoB)’s commitment to recognizing Indigenous land rights. They occur five years after the Maya won an unprecedented legal victory in the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) regarding the recognition of Indigenous land rights. The 2015 CCJ decision affirmed that communal land tenure of Maya communities is commensurate with property rights found in the Belizean constitution. Since the ruling, however, the GoB has not complied and refused to meaningfully engage in delimiting and protecting Maya lands, which are conditions of the CCJ order.

Maya Alcaldes (traditional leaders) led investigations into the recent unauthorized surveying and found that it involves foreign parties, non-Maya individuals from outside of Toledo District, and speculators from southern Belize. Surveyors were claiming between 30 and 400 acres of land, which contravenes the 2015 CCJ order, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), which the GoB adopted in 2007. Land predation of this nature, which violates FPIC, has historically facilitated dispossession, corporate extraction, and environmental damage to Maya lands.

Cease and Desist: The Maya Response

Qʼeqchiʼ and Mopan villages are located throughout the southernmost region of Belize, Toledo District. Within Toledo District, there are 39 Maya communities that comprise over 20,000 Maya people. Each community has two traditional leaders, called alcaldes, meaning 78 alcaldes constitute the TAA. The TAA is the main representative body and highest central authority of the Maya people in the region, which has historically had a complex relationship with the national government. The communities are also supported by an autonomous social movement, the MLA, which is made up of Maya land defenders.

Upon being alerted of the incursions by village leaders, the MLA and TAA issued a formal statement reminding the GoB that it is legally obligated to, “…cease and abstain from any acts, whether by the agents of the government itself or third parties… …that might adversely affect the value, use, or enjoyment of the lands that are used and occupied by the Maya villages, unless such acts are preceded by consultation with [Maya people] in order to obtain their informed consent.”

In an interview reproving the encroachments shortly after they were reported, Maya land defender and MLA spokesperson, Cristina Coc, pointed out that the increase in FPIC violations were coinciding with the run-up to the national election in Belize, which took place on November 11, stating, “…one has to ask the question whether or not it is politically motivated, and whether or not it is related to what we have seen historically in Belize, where around campaign time politicians offer land in exchange for votes.”

Upon denouncing the attempted land grabs at a hearing before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR), the MLA and TAA submitted a request for precautionary measures against the GoB to halt all illegal activity. Rather than an isolated issue related to the ownership of private property, movement activists reiterated that grabbing communal Maya lands poses a grave threat to the material wellbeing and cultural survival of Qʼeqchiʼ and Mopan people who are experiencing the slow violence of dispossession and extractivism.

This is a story about Indigenous resistance to ongoing assertions of post-colonial power, capitalist logics, and Western worldviews. The GoB is based upon a Westminster model of governance imposed by British imperialists that has failed former colonies all over the world. Moreover, the GoB has a track record of abetting multinational corporations while repudiating Indigenous people’s claims to communal land ownership, notions of complex tenure, and right to self-determination. Coc, who has bore witness to decades of state-sponsored FPIC violations, summed up the GoB’s persistent penchant for land grabbing by stating, “there’s always been incursions on Mayan land; this is exactly why we went to the courts (CCJ) to seek affirmation of protection.”

Denial and Disavowal: The State Response

The GoB’s response to the Maya came on October 30. Patrick Faber, leader of the then ruling United Democratic Party, admitted that, in accordance with the CCJ decision, the presence of surveyors without the consent of the Maya would indeed be illegal. But he dismissed the allegations by the Maya and Coc by stating, “I listened very carefully as Miss Coc spoke and there is no evidence to that [surveying] happening… …She is only telling you what she saw and what people reported is happening but no concrete evidence of anything happening.”

Despite the Maya issuing written reports with photographs to both the Lands and Surveys Department and Attorney General, the GoB rejected the claims by suggesting there was no evidence. Incidentally, for nearly a year in 2015-2016, Coc, along with 12 other Maya activists, were detained, jailed, and dragged through the courts by the GoB after protecting a sacred heritage site against similar incursions. Despite the criminalization, all the charges levied against the Maya environmental defenders were eventually dismissed.

Similar to Faber’s response, Belize’s Attorney General, Michael Peyrefitte, implying the Maya were merely trying to make the government look bad, said to Coc, “…if you have a legal issue ma’am, go dah court. To me, you don’t really have a legal issue because if you had a real legal issue, you would go to court, you wouldn’t go to the media.” Peyrefitte then went on to suggest the Maya wanted a “separate country” and that Indigenous people’s self-determination was irrelevant in the face of state power, asserting, “they [the Maya] may not like to hear that… …nothing can stop the executive of the country to do what it feels like it needs to do for the betterment of the country.”

A survey line cut through a forest near the Maya community of Golden Stream. (Julian Cho Society)

The Attorney General’s response ignores the actual allegations of land grabbing being made against the GoB. Instead, Peyrefitte suggests the encroachment claims are irrelevant because “they want their own country,” which is a rhetorical attempt to undermine both Coc’s credibility and the validity of the reports issued by Maya Alcaldes. The state’s evasive response was a divisive disavowal of Maya land rights. And by prioritizing the desires of private capital over Indigenous people’s customary systems, relationships with the environment, and livelihood strategies, which the GoB has a history of, it is also hostile and dehumanizing.

State Authoritarianism vs. Indigenous Autonomy

When we consider the GoB’s response alongside the ongoing struggle for Indigenous land rights in southern Belize, three issues require urgent attention.

Firstly, good faith leadership is lacking because the government refuses to investigate the claims of Maya Alcaldes. The GoB insists that because the Maya used the media to raise awareness about FPIC violations, they do not have a ‘real’ issue. This argument is nonsensical and contrived.

Secondly, when Indigenous people report violations to government agencies, agencies are slow to investigate––if they investigate at all. Moreover, arguing Indigenous people must always operate (i.e. “go to court”) and exist on the state’s terms is colonial. This is not an uncommon refrain from the state, though, as the GoB realizes that going to court for rural subsistence-based Maya communities is an expensive and protracted process. Certain government agents also realize that, even if the courts rule against the state, it can get away with violating decisions and rule of law, as it has done before.

Why, when under legal mandate to protect Maya land rights, are the claims discounted without investigation? Furthermore, in addition to photographs and reports, what would satisfy the state’s need for and definition of ‘concrete evidence’?

Lastly, the imperious tones of Faber and Peyrefitte’s responses are not only dismissive, but dangerous––and not only for the Maya. Peyrefitte says, “…nothing can stop the executive of the country to do what it feels like it needs to do for the betterment of the country.” This is authoritarian nationalism par excellence and should concern the whole of Belize.

The GoB’s lack of rights-based leadership and draconian posturing is nothing new. Back in 2015, when the CCJ ruling was passed in favour of the Maya, the GoB’s Attorney General was quick to diminish Maya customary tenure by stating Indigenous land rights “cannot trump the constitutional authority of the government.” Hence, the state appears only to be willing to take the lead on refuting the rights of Indigenous people and fettering Maya autonomy.

Maya leaders afforded the GoB the opportunity to demonstrate good faith adherence to consent processes and strengthen its relationship with Maya communities. It was also a chance for state officials to denounce FPIC violations, prevent deleterious land encroachments, and uphold its obligation to protect customary Maya land rights, as ordered by the CCJ. Instead, the GoB doubted the veracity of the Alcaldes’ reports, attacked the credibility of Maya people, attempted to turn the larger population against the Maya, and declared to all citizens of Belize it could impose upon them whatever it wanted, arbitrarily, for “the betterment of the country.”

The Reality of Land Grabs under Covid-19

These encroachments on Maya land during the pandemic threaten their livelihoods, says, MLA spokesperson Cristina Coc:

…not only are farms and milpas being affected, but even residential areas where we have our own villages living. This is concerning because it impacts our livelihood, and we have seen throughout the Covid pandemic how valuable land is, and how valuable the production of land is for the food security of Mayan communities and Belizeans alike.

We recognize that the government cannot feed our people, they cannot employ all of our people, they cannot rescue us from this economic spiral that we’re experiencing. But what we can do is provide full security for our people by protecting their tenure on the land…

…it is very alarming that the government would allow such actions–––the Maya communities have been informed and are aware that there is a standing consent order that affirms our rights and protects ancestral rights to lands and territories.

The authoritarian behaviour and contemptuous rhetoric of the GoB continues to disrupt Indigenous life and close avenues for Maya people to exercise their rights and have their voices heard. It is also signalling to all Belizean people that the state is more than willing to sacrifice the rights and wellbeing of the marginalized at the altar of ‘development.’

Filiberto Penados is Chair of the Julian Cho Society and technical advisor to the Toledo Alcaldes Association and Maya Leaders Alliance. His research focuses on Indigenous future-making.

Shelda-Jane Smith’s research focuses on the conceptual, social, and political dimensions of contemporary psychology and biomedical practice, with an emphasis on youth wellness.

Levi Gahman focuses on emancipatory praxis, environmental defence, and engaged movement research. He is author of Land, God, & Guns: Settler Colonialism & Masculinity (Zed Scholar).

This research was supported by a Heritage, Dignity, and Violence Programme Grant from the British Academy under the UK’s Global Challenges Research Fund (Award: HDV190078), for which all the authors are co-investigators and collaborators.