By Bert Schouwenburg

We are grateful to Bert Schouwenburg and to Banana Link for permission to reproduce this article. It was first published in The Morning Star who did not reply to our request for permission to reproduce the article. It was later produced in the first edition of the Banana Trade Blog which is produced by Banana Link (www.bananalink.org.uk )

Trade Union leaders are no stranger to hyperbole but when public sector union, ANEP’s General Secretary, Albino Vargas told delegates at the annual general assembly of SITRAP (Agricultural Plantation Workers Union) that the event came at a historic moment in Costa Rica’s labour history, he was not exaggerating.

The assembly was held on January 20th [2019] in the heart of Limón’s banana growing zone at the Pococí Expo Centre in Guápiles. The 700 SITRAP members and their families were bussed in from all over the region during an operation that, for some, commenced at 3.30am to ensure that everyone was present for breakfast and an 8am start. Previous assemblies had been held at a much smaller venue in Siquirres where SITRAP have their premises, and before that in the main hall of their building itself when active membership of the union was at its lowest ebb.

GMB’s relationship with SITRAP began in 2003 under the auspices of NGO Banana Link’s ‘Union to Union’ programme aimed at establishing direct links with workers in Latin America’s tropical fruit plantations. SITRAP was in dire straits, its membership decimated by a sophisticated and ruthless campaign, headed up by the Costa Rican government, to drive trade unions out of the banana industry altogether. In the early 1980s, the then powerful unions’ fight for better working conditions prompted the employers to close down all their farms on the Pacific coast and throw thousands of people out of work. In a sustained propaganda exercise the closures of what were uneconomic plantations was blamed on trade union militancy and intransigence.

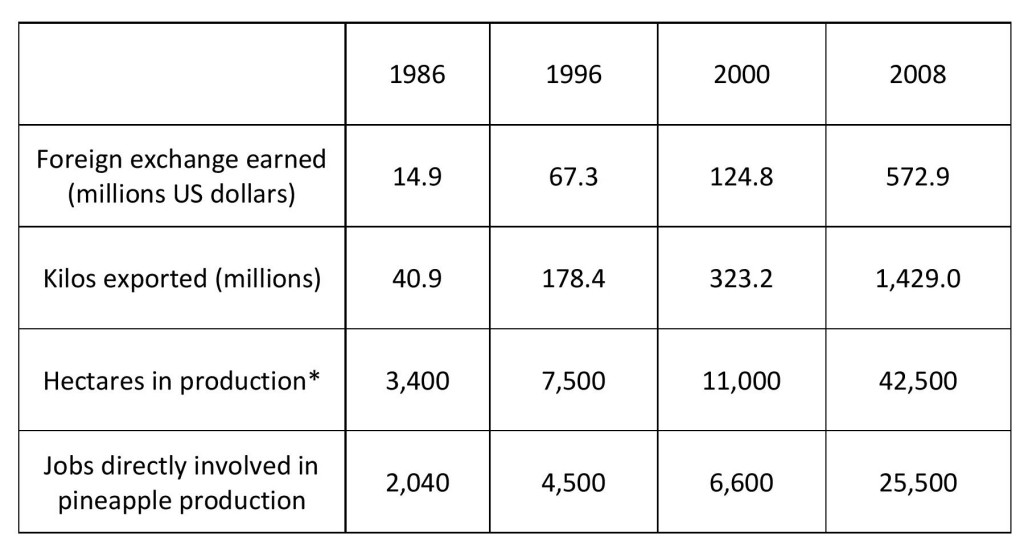

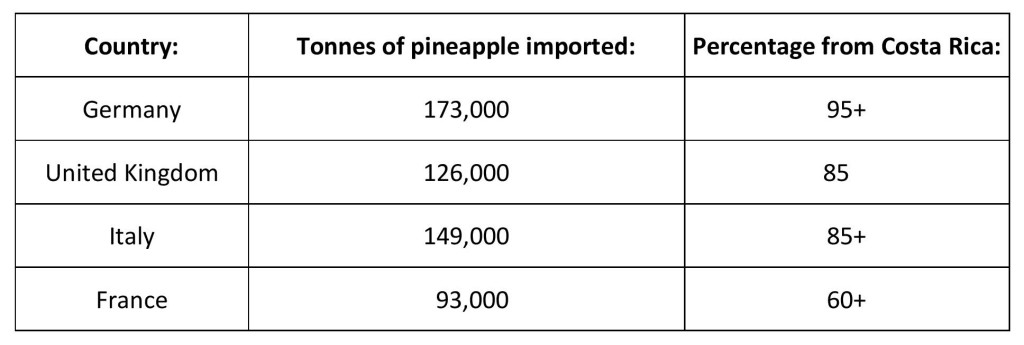

To this day, criticising the unions for the Pacific coast closures is an integral part of the banana producers’ strategy to dissuade workers from forming and joining them. Aided and abetted by the San José dioceses of the Roman Catholic Church, who have described them as being the work of the devil, they have spread the doctrine of ‘Solidarismo’, a concept enshrined in Costa Rican law whereby workers are encouraged to elect representatives to ‘permanent committees’ who then conclude ‘direct agreements’ with management to the exclusion of independent trade unions. Needless to say, these agreements are presented to the committees on a take it or leave it basis with no room for negotiation. Solidarista associations have been formed throughout the length and breadth of not just the banana industry but also in plantations growing pineapples of which Costa Rica is the world’s number one exporter. Where union organisation appears, workers are harassed, intimidated and, if they do not renounce their membership, are sacked and blacklisted.

One of GMB’s first initiatives was to raise funds so that SITRAP could complete much needed renovations to their building in Siquirres, a successful project that led to the assembly hall being dedicated to the late Brian Weller, a much-loved activist from London, in whose name the money was collected. This was followed by a memorandum of understanding between the unions and a two year funding agreement that kept SITRAP afloat and gave them breathing space to build their organisational capacity in an extremely hostile environment.

Slowly, but incrementally, SITRAP built its membership base in hostile multinational company farms belonging to Chiquita, Del Monte and Dole and also in plantations owned by vehemently anti-union national companies such as the Acon Group who made sure that the union could not make the sufficient inroads needed in order to reach the density required to trigger recognition, by sacking members under any pretext. However, a significant breakthrough occurred in January, 2016 when, after an 18 year struggle, the Labour Reform Process Law was put onto the statute book. This landmark piece of legislation dramatically speeded up the glacial pace of Costa Rica’s labour code and enabled workers to bring claims of unfair dismissal to court within days and empowered judges to order immediate reinstatement pending a full merits hearing. At a stroke, the legislation deprived employers’ ability to arbitrarily dismiss trade unionists at will, safe in the knowledge that cases brought against them could take years to be heard. Unsurprisingly, private sector employers are lobbying furiously to have the law overturned.

The cumulative effects of SITRAP’s continuing membership drive, the space afforded to it by the passing of the new law, and the pressure being brought to bear by motivated consumers in European markets allowed the union to make members to such an extent that, after 9 months of negotiation, it was able to sign a recognition agreement in a Del Monte plantation just before the assembly, the first such agreement to be concluded since the 1980s. It was this that prompted ANEP’s General Secretary to comment on the historic significance of the moment.

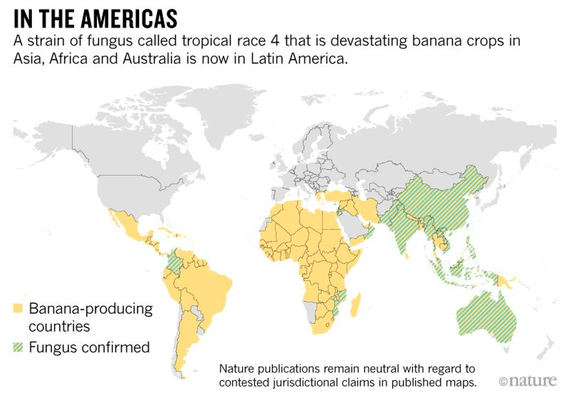

Banana production in Costa Rica, and elsewhere in Latin America, faces an uncertain future. The purchasing power of European and North American retailers has squeezed the margins of the multinational producers who are no longer the dominant force that they once were. The downward pressure on costs has been passed on to workers who find themselves the victims of a race to the bottom as producers react to the price wars of major supermarkets, particularly in the UK. The huge mono-crop plantations, drenched in pesticides, are environmentally disastrous and are prone to disease. So far, the deadly fusarium wilt virus has been kept at bay in Latin America but if it takes hold, that could be the beginning of the end for the industry as we know it and explains why serious thought is now being given to multi-cropping and diversification away from the ubiquitous Cavendish banana that is intensively farmed throughout.

For the thousands of workers in the Costa Rican banana industry, it is essential that they have a collective voice that can be heard, however the industry develops. SITRAP’s re-emergence as a significant player is therefore vitally important and they deserve the continued support of unions like GMB, and UNISON who have also given valuable assistance, especially as so much of the fruit their members produce finds its way into the UK’s fruit bowls.

ANEP have produced the video report of the event below, which includes contributions from the General Secretary of SITRAP, Didier Leiton, Alistair Smith of Banana Link, and Bert Schouwenburg, who represented the GMB at the meeting.

700 agricultural workers attend historic SITRAP assembly from Banana Link on Vimeo.

Thank you for supporting our recent urgent action appeal in support of union members at Costa Rican pineapple producer ANEXCO. More than 23,000 emails have been sent to the company, calling on them to end harrassment of union members and to engage in constructive dialogue with the union SINTRAPEM (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores/as del Sector Privado Empresarial). This massive effort, plus several articles in the trade press and an intervention by the UK’s

Thank you for supporting our recent urgent action appeal in support of union members at Costa Rican pineapple producer ANEXCO. More than 23,000 emails have been sent to the company, calling on them to end harrassment of union members and to engage in constructive dialogue with the union SINTRAPEM (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores/as del Sector Privado Empresarial). This massive effort, plus several articles in the trade press and an intervention by the UK’s

The following article focuses on banana production with an examination of the practices of the major importing company Fyffes. I am grateful to Banana Link for permission to reproduce extracts from their article which appeared in the Make Fruit Fair! Newsletter of 23rd January 2017.

The following article focuses on banana production with an examination of the practices of the major importing company Fyffes. I am grateful to Banana Link for permission to reproduce extracts from their article which appeared in the Make Fruit Fair! Newsletter of 23rd January 2017. “They never contributed to social insurance and now I will not be able to retire or finally rest after so many years spent on the plantations. I have to continue looking for work to survive.” – María Gómez (65) who worked for nearly 30 years as a supervisor at Melon Export SA.

“They never contributed to social insurance and now I will not be able to retire or finally rest after so many years spent on the plantations. I have to continue looking for work to survive.” – María Gómez (65) who worked for nearly 30 years as a supervisor at Melon Export SA. “I got pregnant, and they do not allow pregnancy” – Marys Suyapa Gómez, sacked for being pregnant after working at Suragroh for 15 years

“I got pregnant, and they do not allow pregnancy” – Marys Suyapa Gómez, sacked for being pregnant after working at Suragroh for 15 years “Fyffes must take responsibility for ensuring that their local managements in Costa Rica and Honduras recognise and enter into good faith negotiations with local unions and that company-wide freedom of association and collective bargaining is respected at every level.“ – Ron Oswald, General Secretary, International Union of Foodworkers.

“Fyffes must take responsibility for ensuring that their local managements in Costa Rica and Honduras recognise and enter into good faith negotiations with local unions and that company-wide freedom of association and collective bargaining is respected at every level.“ – Ron Oswald, General Secretary, International Union of Foodworkers.