By Martin Mowforth for the TVOD website

Key words: Costa Rica; pineapple exports; cocaine.

As if problems of labour exploitation, community relations, political bribery, water and soil contamination are not serious enough for pineapple transnational companies, since 2018, and possibly before, shipments of the fresh fruit and processed fruit have become vehicles for cocaine smuggling operations.

(Photo courtesy by AFP / Spanish National Police )

In August 2018 the Spanish police announced that they had seized 67 kilograms of cocaine stuffed inside dozens of hollowed-out pineapples at Madrid’s main wholesale fruit and vegetable market. The shipment had been offloaded at the Portuguese port of Setubal from a ship from Costa Rica. They had then been transported overland to Madrid. The police statement said each pineapple had been “perfectly hollowed out and stuffed with compact cylinders containing 800-1,000 grams of cocaine” and was coated with wax to conceal the smell of the chemicals in the drugs and to avoid its detection (Tico Times, 2018).

In February 2020, in Costa Rica’s Atlantic coast port of Limón, a shipment of over 5,000 one kilogram bags of cocaine (with an estimated value of 126 million euros) was exposed in a container full of canopy plants which were destined for Rotterdam. This was the largest drugs bust in Costa Rica’s history (de Geir, 2020). Three months later, the police in Costa Rica intercepted 1,250 one kilo parcels of cocaine hidden in a shipment of pineapple juice which was waiting to be shipped to the port of Rotterdam. Other 2020 drugs interceptions were also made in January (amongst a shipment of bananas), March (pineapples) and April (bananas) NL Times, 2020).

In August 2020, another container of pineapples destined for Rotterdam was seized by the Costa Rican Drug Control Police (PCD) with $22 million worth of cocaine hidden inside it – 918 packages totalling approximately one ton. The Minister of Security absolved the fruit exporting company of any blame, explaining that the drugs were introduced at some point between the company and the port (Allen 2020).

In February this year (2021), the PCD reported another seizure of cocaine in the Atlantic coast port of Moín, on this occasion including 2,000 packages of cocaine (approximately two tons). Again the packages were hidden in a shipment of pineapples and were destined for Belgium (Agence France-Presse, 2021).

A person holding a cocaine-stuffed pineapple, seized by Spanish police in Madrid. Spenish police said on August 27, 2018, they have seized 67 kilos (148 pounds) of cocaine found inside dozens of hollowed out pineapples at Madrid’s main wholesale fruit and vegetable market. ((AFP Photo / Spanish national police.)

Not surprisingly, Costa Rica now requires that all shipments of fresh pineapple and its related products should be scanned at Costa Rican ports by the General Directorate of Customs (Zúñiga, 2021). The requirement was made by the Costa Rican government in order to defend the reputation and positive image of the country, things that have already been well-tarnished by the Costa Rican pineapple industry.

Sources:

Tico Times (2018) ‘Cocaine-stuffed pineapples shipped from Costa Rica to Europe’, 5th August, San José. (Sourced from Agence France-Presse.)

De Geir, J. (2020) ‘Video: Costa Rica’s biggest-ever cocaine bust was headed to Netherlands’, NL Times, 17th February (Amsterdam).

NL Times (2020) ‘Costa Rican authorities seize 1,250 kilos cocaine destined for Rotterdam’, NL Times, 13th May (Amsterdam).

Allen, A. (2020) ‘Authorities Seize $22 Million Worth of Cocaine Found in Pineapple Shipment’, ANDNOWUKNOW, (www.andnowuknow.com), 21st August, Sacramento, California.

Agence France-Presse (2021) ‘Costa Rica seizes two tons of cocaine hidden with pineapples’, 5th February, Paris.

Zúñiga, A. (2021) ‘Costa Rica draws the line: All pineapple shipments checked for drugs’, Tico Times, 9th February, San José.

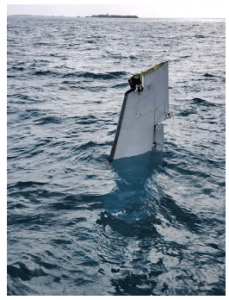

In February last year (2020), Belizean authorities intercepted a Gulfstream II business jet on landing to find it full of 69 bales of cocaine, the largest drugs haul ever made in Belize. (See photo below.) These jets are largely out of service now and can carry a huge payload of drugs. In 2020 four such drug-running business jets were impounded in Belize, but compared with the value of the drugs smuggled and the number of flights which get through, their loss is of little consequence to the cartels. Also a small country like Belize has limited aerial capability to detect and/or intercept such flights.

In February last year (2020), Belizean authorities intercepted a Gulfstream II business jet on landing to find it full of 69 bales of cocaine, the largest drugs haul ever made in Belize. (See photo below.) These jets are largely out of service now and can carry a huge payload of drugs. In 2020 four such drug-running business jets were impounded in Belize, but compared with the value of the drugs smuggled and the number of flights which get through, their loss is of little consequence to the cartels. Also a small country like Belize has limited aerial capability to detect and/or intercept such flights.