By Brittany Oakes

October 2022

La Via Campesina is an international movement that promotes and celebrates agro-ecology as the most suitable form of agriculture to provide for the food needs of humanity. We asked Brittany Oakes who ran workshops on La Via Campesina at the El Sueño Existe Festival in August this year to write a brief article for The Violence of Development website. Brittany interned with the Rural Workers’ Association in Nicaragua, a co-founding La Via Campesina (LVC) member, and has been involved in international Nicaragua solidarity campaigns, including Friends of the ATC and Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign. She currently volunteers with the LVC UK member, Landworkers’ Alliance.

This year (2022) La Via Campesina (LVC), the largest international grassroots social movement in the world, celebrates 30 years of collective organising for food sovereignty. Today, LVC represents more than 200 million rural workers, Indigenous people, foresters, fishers, migrants, peasants and small-scale farmers around the world, spanning 81 countries across five continents. There is a strong Latin American presence through the Latin American Coordinator of Campesino Organisations (or CLOC), which itself represents 84 organisations in 18 countries across Latin American and the Caribbean.

Logos of CLOC and LVC

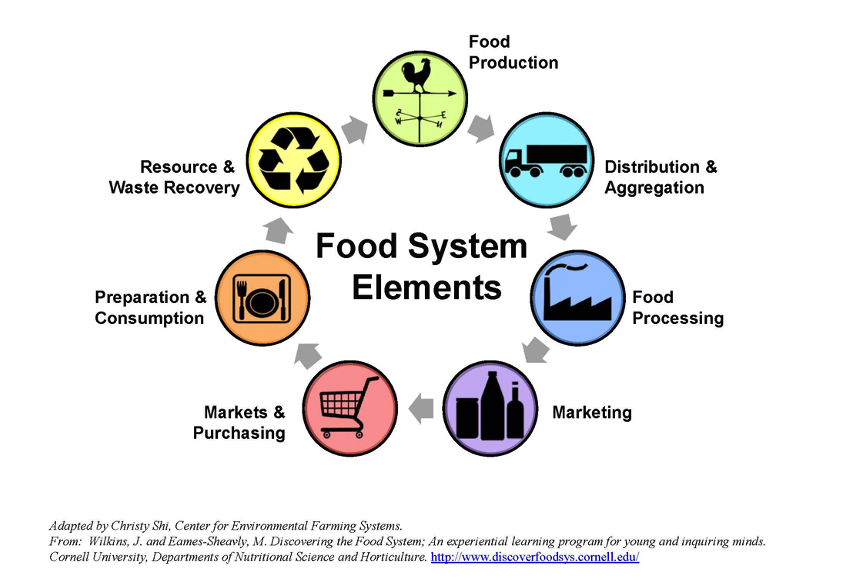

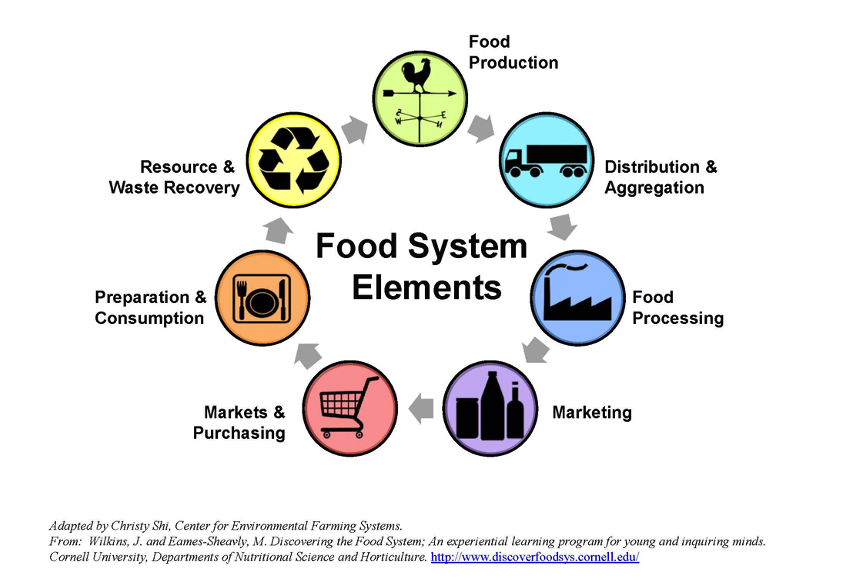

Why and how did this global movement arise, and what is their shared vision of food sovereignty? To understand this, we need to take a step back and look at the food system, and how it has dramatically changed over the past decades.

The dominant globalised, industrial food system

The food system is everything that goes into keeping us fed: from growing, harvesting, packing, processing, and preparing the food, to marketing, consuming and disposing of it. Half of the global workforce (1.3 billion people) are employed in some form of agriculture, with an estimated 2.6 billion deriving their primary livelihoods from the food system as a whole.1

If you look at the dominant food system worldwide today, it is largely controlled by an increasingly consolidated corporate chain. A 2013 report by Oxfam showed the top 10 food companies make a profit of more than £917 billion (GBP) a day and represent more than 10 per cent of the global economy.5 Power is concentrated at the very top of the system, with corporations investing billions in influencing and dictating national and international government policy, and farmers and workers required to become dependent on the terms set by these corporations to make any kind of livelihood.

This model of globalised, industrial food production grew during the Thatcher-Reagan era of international free market policies in the late 1980s and into the early 1990s.3, 6 This shift in the food system has had drastic implications for local markets, and it was during this expansion that LVC coalesced.2

Image of consolidation of food system (from Oxfam, 2013)

The rise of La Via Campesina

At the same time as international trade agreements and forced ‘development’ schemes were imposed in the 1980s, regional and national peasant organisations strengthened and began forming transnational coalitions, particularly across Latin America and especially in Central America. Peasant workers recognised that their influence within their own countries was weakening and they lacked representation in international fora. Grassroots mobilising also took place across India and Europe, with demonstrations of tens of thousands of farmers marching in protest against free trade treaties which severely undercut local markets and threatened the livelihoods of millions. As Europe and the US were celebrating 1992 as the 500 year anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, we also saw that Indigenous and peasant organisations coordinated the Continental Campaign – 500 Years of Indigenous, Black and Popular Resistance from 1989-1992.

In 1992, peasant farmer and rural worker organisations from Central America, the Caribbean, North America and Europe met in Managua, Nicaragua, during a convening of the Rural Workers’ Association (ATC) and the 10th anniversary celebration of National Union of Farmers and Cattle Ranchers. It was at this gathering that the idea took root of forming an international, intercontinental movement without mediating representation by non-governmental organisations (Martínez-Torres and Rosset, 2010). At a follow-up convening in Mons, Belgium, in 1993, more than 70 farm leaders from around the world gathered to formally launch LVC. Through these initial gatherings and subsequent international assemblies, LVC developed a shared vision of food sovereignty.

A shared vision for food sovereignty

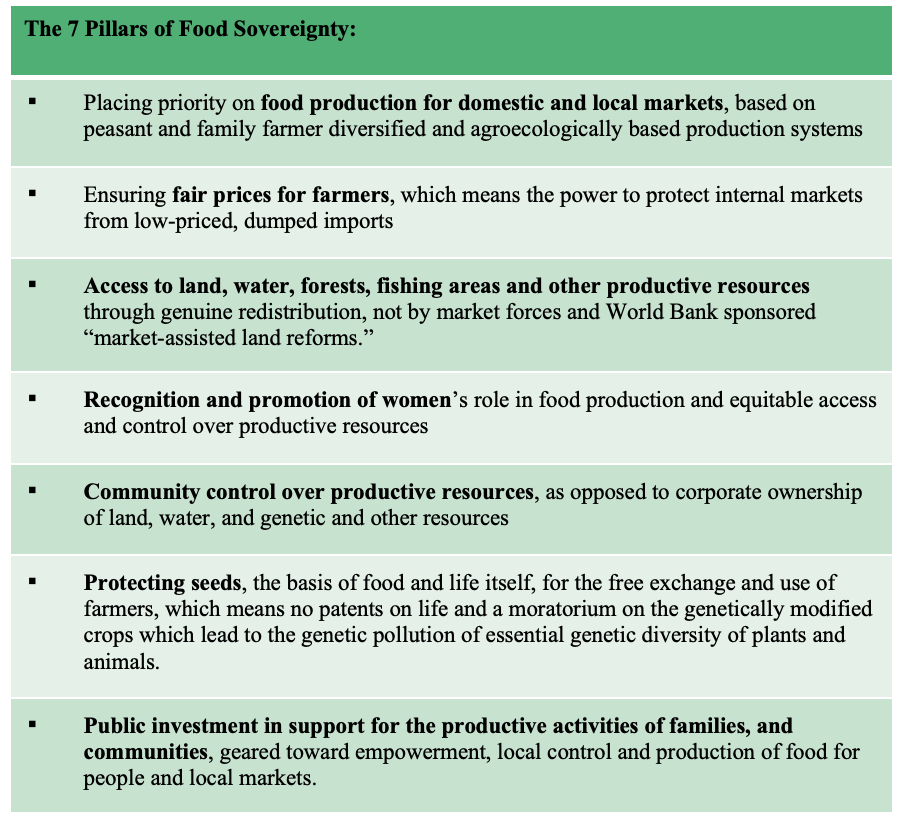

Food sovereignty can be understood as a concept, an ongoing social and political process and a movement. The concept was put forward by LVC, in coordination with other international allies, at a UN Conference in Rome in 1996, and it was refined and developed over the following years into what culminated in the Nyeleni Declaration in 2007.4 The full definition is over a page long; it is radical and holistic, and it should be read in its entirety, but it is often summarised in the first line:

“Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

How does La Via Campesina work for food sovereignty?

LVC member organisations work for food sovereignty at local, national and international levels through a wide range of activities and processes. Lobbying, campaigning, outreach, awareness-raising and political education are crucial for building broader public support to change the dominant food system. LVC focuses on preserving traditional knowledge of sustainable farming methods, including seed saving and protecting Indigenous varieties of seed that are resilient in a changing climate. LVC also supports training and research in traditional farming methods.

With the climate crisis and the many social and political crises we face today, the work and vision of LVC is a beacon of hope for a sustainable and just future based on respect for people and the planet. Around the world we unite in saying, Globalise the struggle, globalise hope!

Learn more about La Via Campesina through their website: https://viacampesina.org/en/

References

- Gladek, E., Roemers, G., Muños, O. S., Kennedy, E., Fraser, M., & Hirsh, P. (2017). The global food system: An analysis. Retrieved from https://www.metabolic.nl/publication/global-food-system-an-analysis/

- Martínez-Torres, M. E., & Rosset, P. M. (2010). La Vía Campesina: The birth and evolution of a transnational social movement. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 37(1), 149-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150903498804

- Masters, J., & Chatzky, A. (2019). The World Bank Group’s role in global development. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/world-bank-groups-role-global-development

- Nyeleni.org. (2007). Nyeleni declaration. Retrieved from https://nyeleni.org/spip.php?article290

- Oxfam. (2013, February 26). Behind the brands: Food justice and the “Big 10” food and beverage companies [Briefing paper #166.] Retrieved from https://www.behindthebrands.org/images/media/Download-files/bp166-behind-brands-260213-en.pdf

- World Trade Organisation. (2019). Understanding the WTO: Basics: The Uruguay Round. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact5_e.htm

ified maize illegal for human consumption in the US, has been found in food aid distributed by the World Food Programme (WFP) in Central America. In February more than 70 environmental, consumer, farmer, human rights groups and unions from six Central American and Caribbean countries denounced the presence of unauthorized Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in food aid distributed by the WFP, and in commercial imports of food originating mostly from the US. The organisations have requested the WFP to recall all food aid containing GMOs immediately.

ified maize illegal for human consumption in the US, has been found in food aid distributed by the World Food Programme (WFP) in Central America. In February more than 70 environmental, consumer, farmer, human rights groups and unions from six Central American and Caribbean countries denounced the presence of unauthorized Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in food aid distributed by the WFP, and in commercial imports of food originating mostly from the US. The organisations have requested the WFP to recall all food aid containing GMOs immediately.