What, then, are we to make of the mining industry? The transnational mining companies appear to operate like gangsters. Despite the companies’ protestations and propaganda, the evidence and testimony about their extreme misdemeanours seem to be undeniable and overwhelming. Their attempt to win us over with the notion of ‘green mining’ must rate as one of the top examples of corporate ‘greenwash’. But we cannot simply dismiss the industry as gangster-like with no redeeming features – so many of our modern lifestyle props and artefacts depend on the mining of minerals: quite apart from the jewellery, gold and coins, gold and many other minerals are used in electrical switches and contacts, components of satellite dishes, computers, telecommunications, televisions and other electronic equipment, medical equipment, in dentistry and many other walks of life.

In today’s world, the idea of a blanket ban on the extraction of minerals from the earth’s surface – the ‘Leave it in the Ground’ campaign – is just too extreme and would be treated as laughable not just by proponents of the mining industry but also by the majority of the world’s population who have benefitted in some way or other from the ‘modernisation’ and globalisation of the world’s economy. So, if the transnational mining companies are not prepared to humanise themselves and to adapt their behaviour to ensure the survival of the planet and its communities – and that prospect certainly seems unlikely – then are there any means by which mining can be made less damaging and more tolerable than it is at present? Is there, for instance, such a thing as artisanal and small-scale mining? Or is that just a hark back to the golden days of the nineteenth century gold rushes?

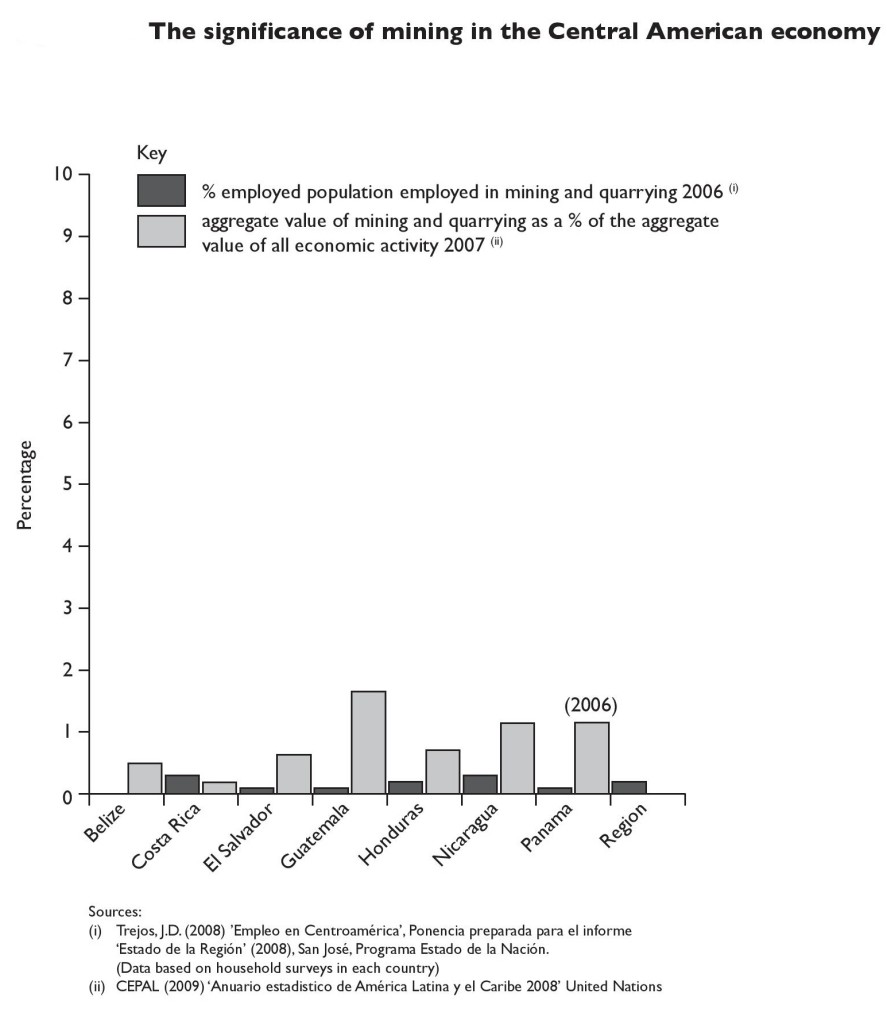

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) reports that worldwide “between 11 and 13 million people directly depend on ASM [artisanal and small-scale mining] for their survival, and 80 to 100 million people engage in ASM as a seasonal activity – more than the number of people employed in large-scale mining.” And “small-scale miners produce 20-25% of all non-fuel minerals worldwide.”[1] The variability in the above data is no less obvious in the region of Central America. In 2003, however, Eduardo Chaparro Ávila gave estimates of the numbers employed in small-scale mines as 3,000 – 6,000 in Nicaragua and 3,000 – 4,500 in Panamá.[2]

ASM, then, is clearly a significant sector of the mining industry, but that does not necessarily mean that it is an answer to the problems caused by large-scale mining. In fact, the evidence suggests that problems associated with water pollution, soil pollution, labour exploitation and health issues are as great for those involved in the small-scale activity as they are for those affected by the large-scale activity. Indeed, the process of separating gold from the earth that contains it requires the use of mercury which has various effects on human health. Reporting on ASM in the Nicaraguan Mining Triangle, James Rodríguez lists these as “disruption of the nervous system, damage to brain functions, DNA and chromosomal damage, allergic reactions, skin rashes, fatigue, headaches, sperm damage, birth defects and miscarriages.”[3] An article by Leslie Josephs about artisanal mining in Costa Rica adds nerve damage and renal failure to this list.[4]

It is perhaps not surprising that the majority of the people who are prepared to undertake such dangerous work are from the poorest and most marginalised sectors of society. As Cristina Echavarría, director of the Mining Policy Research Initiative (MPRI) of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) described to the Conference of Montreal: The International Economic Forum of the Americas in June 2009, “A negative image persisted and expanded of ASM as an unsustainable and unacceptable way of life. Extreme poverty and inequity are also unsustainable and unacceptable. And it is mostly the poorest people, often women and children, who end up in this kind of mining as a last, hopefully temporary, resort to make a living.”[5]

Marty Logan reports that up to the turn of the century, “governments and multilateral institutions operated in the hope that ASM would disappear,” but also that “it became painfully clear that ASM was not going to disappear.” [6] It is also clear that both large-scale and small-scale mining are generally very destructive of the health of humans, of animals and of the environment.

Given this state of affairs, in 2001 the World Bank launched the Communities and Small-Scale Mining (CASM) initiative whose stated goal is “to reduce poverty by improving the environmental, social and economic performance of artisanal and small-scale mining in developing countries.”[7] Amongst other specific objectives CASM tries to formalise ASM so that it can work with the large-scale sector of the industry to the mutual benefit of both. The Mines And Communities organisation points out that this is “certainly a welcome advance on earlier stances which tended to regard small-scale mining as, at best, a hindrance, at worst, as criminal.”[8]

In 2008 in collaboration with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), the MPRI stated its intention and vision that within ten years ASM would be “a formalised, organised and profitable activity that uses efficient technologies and is socially and environmentally responsible.”[9] The vision was soon endorsed by the ILO, the World Bank and a range of NGOs, governments and bilateral programmes.

In early 2010 the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) published a report entitled ‘Working together – how large-scale miners can engage with artisanal and small-scale miners’.[10] Whilst praising some aspects of the report, the organisation Mines And Communities suggests that, despite its stated motives and fine words, this simply does not go far enough to address the shocking nature of much large-scale mining: “It fails … to challenge the unacceptable economic stranglehold some of them [the companies] currently wield over governments and land-based labourers alike.”[11]

In commenting on a report by Earthworks[12], a research and action group on issues of mining, Mines And Communities is critical of the ICMM’s prescription that ASM should lie largely with governments and large-scale mining companies. Instead, it suggests that artisanal and small-scale miners should empower themselves in order to assert their rights. It further suggests that “In the process they are likely to improve their health, gain some economic stability, and be given access to buyers and processers of their products, willing to pay a ‘fair’ price.”[13]

Earthworks believes that it is necessary for artisanal and small-scale miners to adopt principles and standards for responsible ASM and that a range of NGOs could provide such standards. Moreover, there are some NGOs which are in a position to provide a certification system which

would include practices such as respecting human rights; obtaining community consent; guaranteeing revenue sharing and transparency; not operating in areas of armed conflict; respecting workers’ rights and health and safety standards; not using mercury or other toxic chemicals; and not operating in protected areas, among others.[14]

There is no question that such notions are laudable and deserve the support of all parties directly or indirectly involved in the activity of ASM, but their realisation in practice is likely to require far more effort than a statement of those fine words. In Central America, the Costa Rican government is attempting to regulate artisanal and small-scale miners by “urging them to form cooperatives, apply for official mining concessions with environmental permits and pay taxes.”[15] One of the prime reasons for this effort is the government’s concern that these informal miners dump dangerous chemicals into water supplies. Additionally, it is known that some of the miners regularly handle mercury with their bare hands. By the end of 2009, the government estimated that about a half of the miners were already organised into officially recognised cooperatives.

The Costa Rican programme is a worthy one, but in other countries regulation of the ASM sector has not yet featured on the political scene. Moreover, the activities of the ASM sector are often informal and remote, and even illegal, and thus are often beyond the reach of legislators and officialdom.

The prospect that the ASM sector could replace or stand in for the large-scale mining corporations is simply not yet on the horizon.

[1] Marty Logan (2009) ‘Making Mining Work: Bringing poverty-stricken, small-scale miners into the formal private sector’, International Development Research Centre (IDRC), 8 September 2009, www.idrc.ca/en/ev-62120-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html (accessed 11.03.10).

[2] Eduardo Chaparro Ávila (2003) ‘Small-scale mining: a new entrepreneurial approach’, United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC/CEPAL), Natural Resources and Infrastructure Division.

[3] James Rodríguez (2010) ‘Gold Fever: Artisanal and Industrial Extraction in the Nicaraguan Mining Triangle’, http://upsidedownworld.org/main/nicaragua-archives-62/2382-gold-fever-artisanal-and-industrial-extraction-in-the-nicaraguan-mining-triangle (accessed 13.02.10).

[4] Leslie Josephs (2009) ‘Costa Rica assails big risks taken by small miners’, Reuters, 24 December 2009.

[5] Op.cit. (Logan).

[6] Op.cit. (Logan).

[7] Communities and Small-Scale Mining website, www.artisanalmining.org (accessed 14.03.10).

[8] Mines And Communities website, ‘Mining lobby group advocates engaging with artisanal miners’, www.minesandcommunities.org/article.php?a=9890 (accessed 11.03.10).

[9] Op.cit. (Logan).

[10] International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) (2010) ‘Working together – how large-scale miners can engage with artisanal and small-scale miners’, downloadable from www.icmm.com/page/17638/new-publication-on-engaging-with-artisanal-and-small-scale-miners (accessed 14.03.10).

[11] Op.cit. (Mines and Communities website).

[12] Earthworks (2010) ‘The Quest for Responsible Small-Scale Gold Mining’, downloadable from http://earthworksaction.org/pubs/Small-scale%20gold%20mining%20initiatives%20comparison-2010.pdf (accessed 14.03.10).

[13] Mines And Communities website, ‘The Quest for Responsible Small-Scale Gold Mining’, www.minesandcommunities.org/article.php?a=9891 (accessed 10.03.10).

[14] Op.cit. (Earthworks, 2010).

[15] Op.cit. (Josephs, 2009)