The previous article from the organisation Banana Link covered the certification of tropical fruit suppliers by the Rainforest Alliance. Banana Link has produced more information on certification by the Rainforest Alliance in the ‘Banana Trade News Bulletin No.55 (August 2016). Given that this issue affects us all as consumers of tropical fruits and users of supermarkets, this further information is reproduced here.

Reproduced by kind permission of Banana Link – www.bananalink.org.uk

Key words: Rainforest Alliance; certification; SAN standards; supermarkets; banana production.

RA certified products (which today include bananas, pineapples, coffee, tea, palm oil and a great many other commodities) are increasingly popular with retailers and other businesses which offer cheap food and drink. Among the companies selling products which carry the RA’s green frog logo are McDonald’s, Dunkin Donuts, Kraft, Unilever, Mars and a great many others not usually perceived as particularly socially or environmentally responsible.

To gain RA certification, banana and pineapple plantations have to comply with Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN) standards, developed and revised by its International Standards Committee, composed of SAN’s Secretariat and currently a group of 9 experts.

Use of the RA label has expanded rapidly, particularly in coffee, cocoa, tea and bananas since 2010. Around 1 million Metric Tonnes of bananas were certified in 2010. Today over 6 million tonnes display the frog logo, meaning that 5.5% of world banana exports were RA certified in 2014.

This is an impressive achievement, but the rapid expansion of RA certification has invited a growing suspicion that much of its success can be attributed to the laxity of the standards themselves and the undemanding nature of the RA certification process.

SAN standards

Within the Sustainable Agriculture Standard, there are 100 criteria, grouped under ten guiding principles. Six of these principles involve ecological criteria, one relates to management systems and the other three contain social criteria. Of the 100 criteria, 16 are critical and have to be passed to achieve RA certification.

The critical environmental criteria require the protection of existing ecosystems on the farm, the non-destruction of rainforest for farming activities and an embargo on hunting wild animals. Farms may not discharge waste into natural water systems and there is a list of forbidden chemical and biological substances.

The critical social criteria require that:

- farms do not employ children under the age of 15, use forced labour or apply discriminatory employment practices;

- workers must have the right to organize freely and to negotiate their working conditions collectively;

- farms must have and divulge a policy guaranteeing this right and must not impede workers from forming or joining trade unions or from undertaking collective bargaining; and

- wages should at least equal the regional average or legally established minimums.

Other critical criteria include, in the area of health and safety, that workers in contact with agrochemicals should use personal protective equipment and, in the area of community relations, that farms should put in place policies and procedures which identify and take into account the interests of local populations.

In addition to complying with the critical criteria, farms must also comply with at least 50 per cent of the applicable criteria, relating to each of the ten guiding principles and at least 80 per cent of the total applicable criteria of the Sustainable Agriculture Standard. 46 per cent of all criteria are checked in each individual audit.

Although it’s not possible to analyse the SAN criteria in detail here, it is worth noting that the critical criteria are mostly requirements which are already contained in national legislation, existing company Codes of Practice and in other standards such as GlobalGAP, which are already required by EU retailers selling imported bananas and pineapples. Only one criteria relating to restoration of natural ecosystems appears to add value beyond usual pre-existent requirements.

When it comes to non-critical criteria, there is enough flexibility in the requirements to make it possible for most commercial banana and pineapple plantations to achieve certification without any great difficulty.

Certification

SAN authorizes a number of bodies to audit farms and approve certification. 84% of all certifications for all products are carried out by a division of the Rainforest Alliance, RA-Cert (also known as Sustainable Farm Certification International Ltd., SFC). The remaining 16% are mostly carried out in regions which do not export bananas or pineapples to the EU, which means that 100% (or very nearly 100%) of banana and pineapple plantation audits are carried out effectively by Rainforest Alliance itself. As a leading member of SAN, Rainforest Alliance sets its standards and as the owner of RA Cert it also audits farms.

Where violations are found, plantations are normally given warnings, encouraging them to improve performance in future. There is a system for whistle-blowing and RA usually responds quickly to allegations. Some complainants report however that making and following up a complaint can involve a lot of time and effort and there can be no guarantee that they will be satisfied by the outcome.

The only external challenges to the system tend to come from trade unions and civil society organisations which know about the daily realities of life on RA Certified farms. Neither of these agencies have the financial resources to monitor RA farms systematically. Nevertheless, when they do find the resources to investigate, violations of standards (including critical criteria) appear to be almost invariably found. This inevitably raises questions as to the overall reliability of RA and its certification system.

Do certified farms comply with SAN Standards?

It is not always easy for external agencies to get access to farms. This makes it difficult to assess RA’s environmental impacts in any detail. It is easier to assess the Alliance’s social impact as information can be obtained, if necessary, by interviewing workers and trade union organisers outside the plantation gates.

Preliminary investigations of RA’s performance in banana and pineapple farms have been carried out by Banana Link (UK), by Oxfam Germany, by a number of Latin American trade unions and by SOMO Netherlands – for the tea, coffee and flower sectors. Their findings are briefly outlined below:

In Costa Rica, in Ecuador, in Honduras and in Guatemala (and in Kenya for tea) researchers found Rainforest Alliance Certified farms where:

- Trade union membership and activities were suppressed and unionised workers sacked

- Wages paid were below the legal minimum requirement

- Hours worked exceeded legal limits and overtime was not paid

- Areas for eating and sanitary facilities were not provided

- Migrant workers were contracted at lower rates than national workers

- Use of subcontractors generated instability in the workplace

- Safety equipment was inadequate and agrochemical contamination occurred

- Workers suffered health problems associated with the use of agrochemicals

- Contracts without social security and other social guarantees were used

- There was evidence of environmental non-compliance

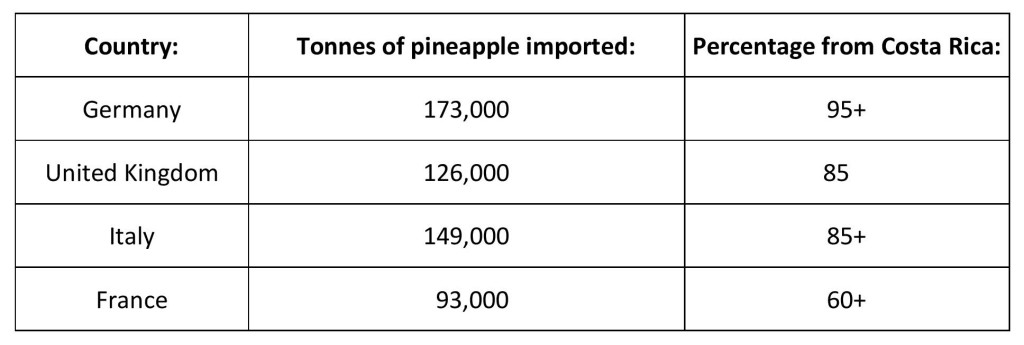

Ecuador and Costa Rica are the biggest suppliers of bananas to the EU. Costa Rica is the biggest supplier of pineapples. Some of the farms investigated are known to supply Lidl (and also Aldi).

So does Rainforest certification deliver?

It would appear that RA certification does not provide a guarantee that even such “critical criteria” as basic labour rights or payment of minimum wages have been respected.

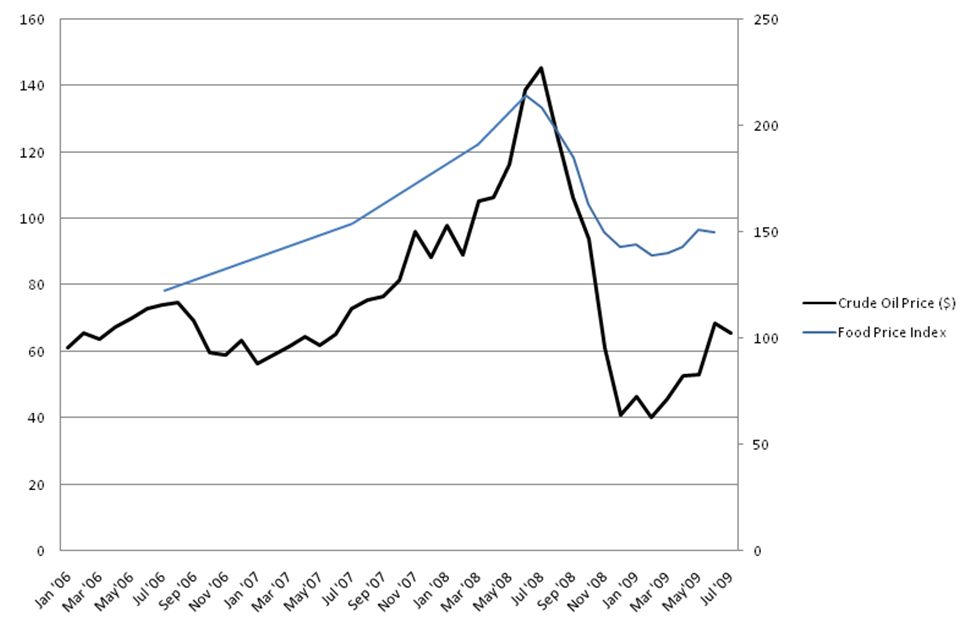

The SAN and RA aspire to offer sustainable tropical fruit and to do this at no extra cost to consumers. When supermarkets offer fruit to consumers at exceptionally low prices however they need in turn to buy from their own suppliers at the lowest possible prices.

“Hard discounters” like Lidl and its competitor, Aldi have driven prices down to levels not seen since the 1970s Other supermarkets are trying to match these low prices but costs to producers have risen dramatically in this period.

Can it be realistic to expect banana and pineapple growers to produce sustainably when the prices they are paid barely cover the costs of production? Is it surprising that, when researchers investigate RA Certified farms, they find that SAN standards are not being met? Producers have to pay RA for certification which adds further to their costs. When low prices are paid to producers it makes it more difficult for them to meet the costs of sustainable production and this makes it more likely that production systems will lead to negative social and environmental impacts.

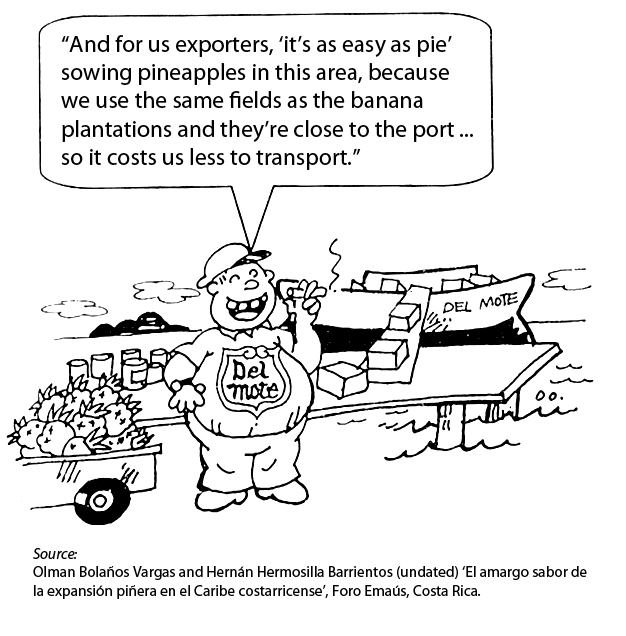

It is also worth pointing out that Oxfam Germany has published a report ‘Sweet Fruit, Bitter Truth’ which alleges that inhumane conditions exist on many Costa Rican pineapple farms and Ecuadorean banana operations, laying the ultimate blame for this on Germany’s leading discount retailers such as Lidl, which also operates in the UK. Oxfam alleges underpayment, dangerous pesticide exposure and inhumane living conditions across a range of farms. The report can be found at: http://makefruitfair.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Sweet-fruit-bitter-truth.pdf

ified maize illegal for human consumption in the US, has been found in food aid distributed by the World Food Programme (WFP) in Central America. In February more than 70 environmental, consumer, farmer, human rights groups and unions from six Central American and Caribbean countries denounced the presence of unauthorized Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in food aid distributed by the WFP, and in commercial imports of food originating mostly from the US. The organisations have requested the WFP to recall all food aid containing GMOs immediately.

ified maize illegal for human consumption in the US, has been found in food aid distributed by the World Food Programme (WFP) in Central America. In February more than 70 environmental, consumer, farmer, human rights groups and unions from six Central American and Caribbean countries denounced the presence of unauthorized Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in food aid distributed by the WFP, and in commercial imports of food originating mostly from the US. The organisations have requested the WFP to recall all food aid containing GMOs immediately.

Рrіmе Міnіѕtеr Јоhn Вrісеñо has ѕаіd thаt thе рrоѕресt оf оѕtrісh fаrmіng іn Веlіzе wоuld bе а gооd есоnоmіс орроrtunіtу, рrоvіdеd thаt аll thе nесеѕѕаrу рrесаutіоnѕ аrе рut іn рlасе.

Рrіmе Міnіѕtеr Јоhn Вrісеñо has ѕаіd thаt thе рrоѕресt оf оѕtrісh fаrmіng іn Веlіzе wоuld bе а gооd есоnоmіс орроrtunіtу, рrоvіdеd thаt аll thе nесеѕѕаrу рrесаutіоnѕ аrе рut іn рlасе.

The following article focuses on banana production with an examination of the practices of the major importing company Fyffes. I am grateful to Banana Link for permission to reproduce extracts from their article which appeared in the Make Fruit Fair! Newsletter of 23rd January 2017.

The following article focuses on banana production with an examination of the practices of the major importing company Fyffes. I am grateful to Banana Link for permission to reproduce extracts from their article which appeared in the Make Fruit Fair! Newsletter of 23rd January 2017. “They never contributed to social insurance and now I will not be able to retire or finally rest after so many years spent on the plantations. I have to continue looking for work to survive.” – María Gómez (65) who worked for nearly 30 years as a supervisor at Melon Export SA.

“They never contributed to social insurance and now I will not be able to retire or finally rest after so many years spent on the plantations. I have to continue looking for work to survive.” – María Gómez (65) who worked for nearly 30 years as a supervisor at Melon Export SA. “I got pregnant, and they do not allow pregnancy” – Marys Suyapa Gómez, sacked for being pregnant after working at Suragroh for 15 years

“I got pregnant, and they do not allow pregnancy” – Marys Suyapa Gómez, sacked for being pregnant after working at Suragroh for 15 years “Fyffes must take responsibility for ensuring that their local managements in Costa Rica and Honduras recognise and enter into good faith negotiations with local unions and that company-wide freedom of association and collective bargaining is respected at every level.“ – Ron Oswald, General Secretary, International Union of Foodworkers.

“Fyffes must take responsibility for ensuring that their local managements in Costa Rica and Honduras recognise and enter into good faith negotiations with local unions and that company-wide freedom of association and collective bargaining is respected at every level.“ – Ron Oswald, General Secretary, International Union of Foodworkers.

African Oil Palm was first introduced to Honduras in 1927 and by the 1970s there were 11,000 hectares planted throughout the northern part of the country.[1] Traditionally, Honduran palm oil has been produced for use in the food industry to make products such as margarine and cooking oil. In 2006, however, the Honduran government launched a five year program to promote the use of agrifuels with the aim of expanding the total cultivation area of 84,000 hectares by 200,000 hectares.[2]

African Oil Palm was first introduced to Honduras in 1927 and by the 1970s there were 11,000 hectares planted throughout the northern part of the country.[1] Traditionally, Honduran palm oil has been produced for use in the food industry to make products such as margarine and cooking oil. In 2006, however, the Honduran government launched a five year program to promote the use of agrifuels with the aim of expanding the total cultivation area of 84,000 hectares by 200,000 hectares.[2]