Category: Chapter 2

Effects of Costa Rica’s Seed Law

All commercial seeds in Costa Rica need to be registered and approved by the National Seed Office, and comply with its requirements and procedures. This means legal action and fines for any farmer who sells or exchanges non-approved seed. Any possibility of creating exceptions to this rule will need further regulation, and cannot be taken as read.

Under the promise of raising quality, seeds must comply with rigid standards ensuring uniformity, distinctness, and stability. However, diversity and homogeneity do not mix, and this requirement for homogeneity effectively makes traditional native seed varieties illegal. These are the very seed that are able to adapt to the variety of climates, soils and agricultural practices employed by campesino agriculture.

Traditional seed needs to be registered. This transfers to seed companies the raw material to select new commercial varieties.

The homogenisation of agriculture severely reduces food diversity. This legally restricts which seeds are permitted for use and ignores the wealth of genetic diversity represented in traditional seeds. Loss of seed varieties represents erosion of the genetic pool, reduction in pest and disease resistance, greater use of fertilisers, pesticides and fungicides, and fewer food options available for the population.

Food costs will rise for everyone. Greater agricultural inputs and imposed registration and certification costs inevitably filter down to the consumer.

Spray-flavoured pineapple

Doug Specht

GMOs in Honduras and El Salvador

The planting of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) is legal in Honduras and El Salvador but illegal in the rest of Central America.

In 2002, the Honduran Government approved Monsanto’s request to plant MON-810 Bt maize cultivars (Otero, 2007). This is corn with genes from Bacillus thuringiensis – a bacterium that possesses an insecticide effect – so pests that eat the corn die.[i]

Transnational fruit corporations, such as Dole and Chiquita, are also thought to be experimenting on transgenic bananas (Otero, 2007).

According to Jaffe (2003), Honduras is one of the few Latin American counties with an operational biosafety regulation. However its biosafety “Acuerdo” of 1998 simply says “proper measures have to be taken to prevent the negative effects of GMOs on human health and the environment”. The Honduran Ministry of Agriculture, the designated authority to regulate GMOs and evaluate requests for field trials and releases, does not have any specific criteria for such evaluations.[ii]

Monsanto said that by 2007, the company’s GMOs accounted for 15% of the country’s corn production but predicted this would increase to 50% by 2012.[iii]

El Salvador became the second country to allow the cultivation of GMOs when it approved the experimental planting of Monsanto’s YieldGard® Corn Borer with Roundup Ready® Corn 2. The products were planted by the Centro Nacional de Tecnologia Agropecuaria y Forestal (CENTA) which has stations in San Andres, Ceda Izalso and Santa Cruz Porrillo.[iv]

Monsanto admits it was instrumental in securing the government statement which first outlined the use of GMOs which came after the National Congress of El Salvador eliminated the vote against article 30 – which forbade GMO activity – and new biosafety regulations were published.[v]

The company says a biotechnology framework is also being implemented in Guatemala in 2009 and it hopes more Central American countries will adopt Monsanto technologies. But while extensive field trials on the effects of GMOs to human health and the environment remain incomplete, other Central American countries have upheld their ban on GMOs.

[i] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transgenic_maize

[ii] Gerard Otero. Food for the Few: Neoliberal Globalism and Biotechnology in Latin America (2007)

[iii] Rita Perdomo, Monsanto’s Marking Manager, quotes in http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93310225 (Accessed 20/07/09).

[iv] http://www.monsanto.com/monsanto_today/2009/el_salvador_to_adopt_gmos.asp (Accessed 20/07/09).

[v] See note 4.

US interferes in El Salvador’s seed distribution practices

From CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador), 27 May 2014

Rather than following through on Secretary of State John Kerry’s promise to “pursue a positive and constructive relationship” between the US and El Salvador, the US government is demanding that the Salvadoran government eliminate a crucial element of a food security and poverty reduction program in order to receive development aid from the Millennium Challenge Corporation.

Since 2011, the FMLN-Funes administration has been purchasing locally-produced corn and bean seeds from small-scale farmers and distributing them free-of-charge to other small-scale farmers to promote domestic seed production, ensure food security and improve the livelihoods of family farmers, impoverished after decades of corporate-driven agricultural and free trade policies.

Now, US Ambassador Mari Carmen Aponte has announced that El Salvador must allow foreign corporations to bid on the same seed contracts currently offered to local producers in order to receive $277 million in development aid from the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). Read more background on the situationhere.

It’s outrageous that the US government is using development aid to promote the interests of Big Agra giants like Monsanto at the expense of Salvadoran farmers and families.

Take Action Today in Solidarity with El Salvador’s Family Farmers!

Sign the PETITION to tell Secretary John Kerry to:<http://org2.salsalabs.com/dia/track.jsp?v=2&c=6eBoty8CMMSIyTq5gY6c4Pd3raI0fjgc>

• Stop conditioning $277 in development funds on El Salvador cutting support for its family farmers

• Quit using international aid to influence the Salvadoran government’s sovereign policy decisions<http://org2.salsalabs.com/dia/track.jsp?v=2&c=70scaSTTU3ilKVSGtHN5r%2Fd3raI0fjgc>

Deadline: The petition will close on Thursday, June 5th, so it can be delivered to Secretary Kerry.

La Vía Campesina

La Vía Campesina describes itself as an ‘international movement of peasants, small- and medium-sized producers, landless, rural women, indigenous people, rural youth and agricultural workers'[i]. Deriving its name from the Spanish phrase ‘la vía campesina’ meaning ‘the way of the peasant’, La Vía Campesina was formed in May 1993 at Mons in Belgium where it was constituted as a world organisation and defined its structure. It is an autonomous movement, with no political affiliation and with members from 56 countries from Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

La Via Campesina has three main objectives:

(1) To defend peasant, family farm-based production: production should be sustainable and carried out with local resources and in harmony with local culture and traditions. It believes communities can produce the optimal quantity and quality of food with few external inputs. Production is geared towards family consumption and domestic markets.

(2) To defend people’s food sovereignty: the right of peoples, countries and state unions to define their agricultural and food policy without the ‘dumping’ of agricultural commodities into foreign countries. Food sovereignty and sustainability are a higher priority than trade policies.

(3) Decentralised food production and supply chains: the current industrialised agribusiness model has been deliberately planned to dominate all agriculture activities. This model exploits workers and concentrates economic and political power. La Vía Campesina advocates a decentralised model where production, processing, distribution and consumption are controlled by the people and communities themselves, not by TNCs.

La Vía Campesina promotes seven principles of food sovereignty[ii]:

- Food. A basic human right: access to sufficient, safe, nutritious and culturally appropriate food should be a constitutional right.

- Agrarian reform. Agrarian reform is required to give landless and farming communities ownership and control of the land they work. Indigenous territories must be returned to indigenous peoples.

- Protecting natural resources. Food sovereignty demands the sustainable use of natural resources: land, water, seeds and livestock breeds.

- Reorganising food trade. Food must be recognised first as a source of nutrition, and only secondly as an item of trade. National agricultural policies must prioritise production for domestic consumption and food self-sufficiency. Food imports must not displace local production nor depress prices.

- Ending the globalisation of hunger. Food sovereignty is directly undermined by the growing control of multinational corporations and multilateral organisations over agricultural policies. Regulation of TNCs is urgently needed.

- Social peace. Food must not be used as a weapon. Displacement, forced urbanisation and repression of smallholder farmers cannot be tolerated.

- Democratic control. Smallholder farmers must have must have direct input into agricultural policies at all levels. Rural women in particular must be granted direct decision-making rights on food and rural issues.

[i] Food Sovereignty: A Right for All Political Statement of the NGO/CSO Forum for Food Sovereignty, 13 June 2002, Rome.

[ii] Summarised from Ed Hamer ( April 2009) ‘Ploughs into Swords’, Ecologist,

Growing Coffee without Endosulfan

Key words: coffee cultivation; pesticides; endosulfan; Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs); Coffee Berry Borer beetle (CBB); Pesticide Action Network (PAN); field hygiene.

ENCA member Stephanie Williamson, who works for Pesticide Action Network (PAN) UK reports on farmers’ successful experiences from Central America

Endosulfan is a highly hazardous and persistent insecticide responsible for many poisoning incidents, including fatalities, in developing countries and for harm to wildlife. The PAN network has campaigned for over a decade for it to be banned. A massive step forward was achieved in 2011 when international policy makers added endosulfan to the list of pesticides on the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), for global phase out. While over 50 countries have now banned it, farmers in the coffee and cotton sectors continue to use it in some parts of the world, including several Latin American countries.

To find out how these farmers can shift to safer alternatives, PAN UK worked with the coffee sector to interview farmers certified under standards such as Fairtrade, organic, and Rainforest Alliance. These standards have prohibited farmers from using endosulfan for 3 or more years, so certified farmers have developed good experience in managing the key pest, Coffee Berry Borer beetle (CBB), by other methods. We interviewed 22 farmers in Colombia, Nicaragua and El Salvador, from small and medium family farms and large estates, to learn what methods they use and how they had made these changes.

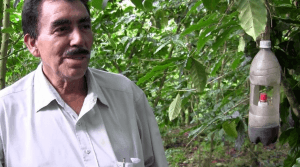

Don Abelino Escobar, Farm Manager, Belmont estate, Santa Tecla, El Salvador with one of his home-made traps, showing the methanol:ethanol dispenser. Credit: P Lievens, PAN UK

In El Salvador, several estates are now using traps baited with a mix of methanol and ethanol to attract the female adult borers when they start to emerge from fallen berries at the start of the rainy season. This method has been developed by the national coffee research institute PROCAFE and promoted to farmers by COEX export company. By trapping large numbers of female beetles and preventing them from breeding, pest levels in the developing coffee berries can be much reduced.

Don Abelino, farm manager for Belmont estate in Santa Tecla (El Salvador), a zone where CBB levels can often be high, recounted how he formerly applied endosulfan twice a year in plots which needed control. While endosulfan could be very effective, if it rained shortly after application, he would need to spray again, at further cost. At other times, an application would simply fail to control the pest and levels would rise, requiring yet more spraying. Since COEX agronomists introduced him to trapping as an alternative, he has been delighted with the results, stopped all endosulfan use and succeeded in gaining Rainforest certification for the estate. Furthermore, he no longer risks his workers suffering ill health from pesticide poisoning and is not contaminating the environment with powerful chemicals. Don Abelino’s experience is that trapping is very easy, very cheap and very effective. Approximate costs per hectare for trapping are US$12, compared with US$70 for two endosulfan spraying rounds.

In Nicaragua, Fairtrade co-operatives have introduced the traps too, with very good results for their members. They are also promoting use of biological pesticides based on a strain of the naturally occurring fungus Beauveria bassiana, which infects and kills CBB without affecting other insects. Organic farmers have found using the fungus extremely useful in their situation. The Miraflor Union of Cooperatives in Estelí has a small Beauveria production unit and sells the product to its members, along with training farmers in how to handle and use it effectively, given that it is a living organism and not a chemical.

All farmers we met are also doing field hygiene as the backbone of good CBB management. These include sanitary picking of bored berries or early maturing berries and collecting fallen berries and dried berries left on trees after the main picking season. These practices are essential to reduce the amount of pest breeding sites and reduce CBB levels in the following season. Farmers explained that the labour cost of these sanitary collections should be seen as an investment in achieving good quality coffee.

Our findings show that it is perfectly possible to achieve good CBB control without using endosulfan, across a range of farm sizes, climate zones and altitudes, pest pressure levels, and coffee production systems. We’ve also shown that methods which avoid pesticide use can be similar in cost, or sometimes cheaper. More governments need to take action to ban endosulfan in their countries, so that safer alternatives can be given a fairer chance.

You can watch four YouTube videos (in English and Spanish) of farmers telling their experiences via www.pan-uk.org/projects/growing-coffee-without-endosulfan

This work was kindly funded by the Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the Sustainable Coffee Programme powered by IDH and the ISEAL Alliance of sustainability standards.

In Central America, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica have still not banned endosulfan.

Gangster tactics against the unions in the pineapple industry

This figure is referred to in the book as Box 2.1 (Page 35)

Didier Leitón Valverde

Didier Leitón Valverde is a leader of the trade union SITRAP, the Costa Rican agricultural and plantation workers union. At 7:30 pm on 5 October 2005, after a meeting with workers on the Cahuita and Tortuguero plantations owned by the company Desarrollo Agroindustrial de Frutales S.A., he left for home on his motorbike. On the way he was attacked by unidentified assailants who had barred the road with a rope. He was insulted, beaten up, dragged across the ground and threatened with death. His identity papers, money and motorbike were stolen. The course of events suggests that the assailants had been informed of his movements and were not there by chance.

Didier Leitón Valverde knew that the road was not safe after dark and that taking it was risky. He would have preferred leaving earlier but the plantation owners had given him no choice but to hols the meeting late. He had agreed because he knew that the workers were victims of an aggressive anti-union campaign and it was important to him not to let them down.

Source: Peuples Solidaires (7 February 2006) ‘Costa Rica: Unionists Attacked’, France, www.peuples-solidaires.org/

Aquiles Rivera

Aquiles Rivera is a Costa Rican trade unionist member of the SITEPP union (Public and Private Enterprise Workers’ Union). He has exposed and fought against environmental problems caused by pineapple cultivation in the south of the country and labour problems experienced in the pineapple plantations. In May 2009 he was followed by four unidentified persons who stopped him in a dark area and warned him to stop what he was doing or he would be silenced. His 14 year old son was also threatened.

At the same time, the SITEPP office was also broken into and fifteen folders stolen, among them being documents about the use of chemicals in the area, windows were broken and other equipment damaged.

Pindeco denied any link with this event or any other persecution of SITEPP.

Aarón Sequeira (20 May 2009) ‘Amenazas de muerte y destrucción de oficina’, Prensa Libre.

Semanario Universidad (8 July 2009) ‘Comunidades pagan costosa factura’, Semanario Universidad, San José, Costa Rica.

Michelle Soto (14 June 2010) ‘Luchar Con la Vida’, Perfil, www.perfilcr.com/contenido/articles/3176/7/25-anos-de-lucha-ambiental/Page7 (accessed 10.01.11).

Water contamination from pineapple production in Costa Rica

Due to the peculiarity of the fruit and its production cycle, which is falsely accelerated, approximately 60 per cent from every tonne of chemicals used in the cultivation of pineapples goes directly into the environment.[1] This is of primary concern to the communities of Cairo, La France, Milano and others in the Siquirres district of north-eastern Costa Rica. In 2007, the agrochemicals Bromacil (associated with thyroid, liver and kidney cancer), Diluron and Tridamefón (also known to be carcinogenic and prone to induce chromosome abnormalities) were detected in water sources here.[2] Despite article 31 of Costa Rica’s Water Act requiring a protection perimeter of no less than 200m in radius, pineapple crops are less than 20 meters from water sources in some of these areas.[3] Rashes on the skin are now commonplace, and an increase in asthma and miscarriages have been recognised.[4]

Another example of environmental contamination as a result of pineapple production comes from Del Monte’s ‘Babylonia’ farm on the Caribbean coast. Studies have found evidence of the carcinogenic herbicides Bromacil and Diaron being prominent in the water source, thereby rendering it unfit for consumption. For the last 3 years pineapple workers have been fighting this case. The government’s only response is to bring in tanks of potable water at a cost of US$27,000 a month. A new reservoir would cost US$80million.[5]

The journal Surcos claims that some 6,000 people in the Atlantic zone are affected by this contamination and that the Costa Rican Water and Sanitation Institute’s water tests “confirm the presence in domestic water of toxic agro-chemicals used on the pineapple plantations”.[6]

The Biodiversity Act article 109 establishes that the alleged polluter is the one who must prove they are not responsible for the damage caused; but this case remains unresolved due to controversy over the law regarding the tolerable limits of such agrochemicals in potable water.

[1] Omar Alvarado Salazar, July 2008, Pineapple production in Costa Rica. FRENASAPP, www.detrasdelapina.org.

[2] Gabriela Square, September 2008, Legalisation of pollution of water for human consumption (the case of Diuron and Bromacil). FRENASAPP, www.detrasdelapina.org.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Alex Leff (April 2009) ‘Costa Rica’s pineapple country is no piña colada’, Global Post: Inside Costa Rica, www.insidecostarica.com/dailynews

[5] Didier Leiton Valverde of SITRAP, presentation to Environmental Network for Central America (ENCA), 17/06/10, London.

[6] Surcos (July 2010) ‘Comunidades y FRENASAPP luchan contra piñeras y demandan a empresa Del Monte’, Surcos 32, Costa Rica.

Nemagon and DBCP

The pesticide Nemagon contains the active chemical DBCP (Dibromochloropropane) and was used for many years on banana plantations to kill nematode pests in the soil. Shell and Dow had conducted animal studies in the 1950s that found that exposure to DBCP led to sterility as well as liver, kidney and lung damage.

Nemagon was banned in 1977 in the United States after it was linked to sterility in workers at an Occidental Chemicals plant in California. Since then experimental evidence from animals has shown it to cause brain and kidney damage, and it is considered a highly toxic and likely highly carcinogenic compound. Regular contact with the toxic chemical has been linked to birth defects, sterility, skin diseases and cancer. After its ban in the United States, the companies continued to export their existing stocks to Nicaragua where it was used by Standard Fruit on banana plantations.

The chemical can be absorbed by ingestion, inhalation or skin contact, and persists for decades in the water and soil of contaminated areas, giving it a particularly dangerous legacy.

Sources:

Banana Trade News Bulletin, no. 27, January 2003.

Stephanie Williamson (March 2003) ‘Nicaragua backs its banana workers’ fight for compensation’, ENCA Newsletter no 33, London: ENCA.

ENCA (July 2004) ‘Banana workers die in march to Managua’, ENCA Newsletter no.36, London: ENCA.

James Watson (December 2010) ‘Nemagon and the Nicaraguan bananeros’, ENCA poster.

Pesticides in Costa Rica’s banana zones seriously affect pregnant women

By Pablo Rojas in www.crhoy.com and sent to ENCA by Didier Leitón Valverde, General Secretary of SITRAP, the Union of Plantation Agriculture Workers in Costa Rica. The original report on which the article is based can be found at: http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/advpub/2014/9/ehp.1307679.pdf

(Translated by Martin Mowforth)

Key words: pesticides; pregnancy; banana plantations; aerial fumigation.

A study published in the international journal ‘Environmental Health Perspectives’ warns of the risk to pregnant Costa Rican women who live near plantations where certain pesticides are frequently used.

The pesticide mancozeb is used to treat banana plantations. According to the report, the pregnant women who were examined in the analysis record a significant amount of etilentiourea (ETU) in their urine. This is a component of the mancozeb pesticide.

“From March 2010 to June 2011, the study included 451 women, of whom 445 gave urine samples which were analysed for ETU. The analysis showed that the amount of ETU found was higher than the quantities found in countries like the USA, Italy and England, at an average rate of five times more ETU in their urine,” explained Berna van Wendel de Joode of the Regional Institute of Toxic Substances of the National University (IRET-UNA) which took part in the research.

Along with IRET-UNA, the Lund University, the Swedish Karolinska Institute, the University of Quebec in Canada and the University of Berkeley California took part in the study. This is the first study which has detected the presence of herbicides in the urine of pregnant women who live in areas around plantations. A small part of the sample were agricultural labourers during their pregnancy and a half of their partners worked on banana plantations.

“Current regulations covering fumigation areas appear to be insufficient to prevent the contact of women with this pesticide, but according to the study’s results it would be possible to take measures to reduce the contact – measures such as: reducing the frequency of fumigations; replacing aerial fumigation with techniques with lower dispersal; and implementing additional measures to diminish the drift generated by aerial applications. These measures would probably reduce the environmental and worker contact with the pesticide,” explained the researcher.

A quarter of the women lived within 50 metres of the plantations. According to the data, some women had higher levels than others because they were living within the banana plantations, and were working there during their pregnancy or were washing clothes for their families.

“Using the data on the amounts of ETU found in the urine, researchers estimated the quantity of the substance which was entering the body each day. For three quarters of the women, their estimated dose was greater than the Integrated Risk Information System’s reference indicator of the US Environmental Protection Agency. For a quarter of them it was double the level of the reference indicator, and for a tenth it was three times higher,” said the official statement provided by the UNA.

The major concern is that herbicides directly affect thyroid illnesses. Other cases of this have occurred in Mexico and the Philippines and it is held from these cases that the regulations for aerial fumigation continue to be weak.

“The researchers show the importance of increasing the distance between the bananas and the houses, planting natural barriers and implementing an automatic system for washing work clothes so that they aren’t washed alongside other items in the workers’ houses,” stated the document.

Thyroid hormones are essential for the healthy development of the foetus and for a healthy pregnancy in general.

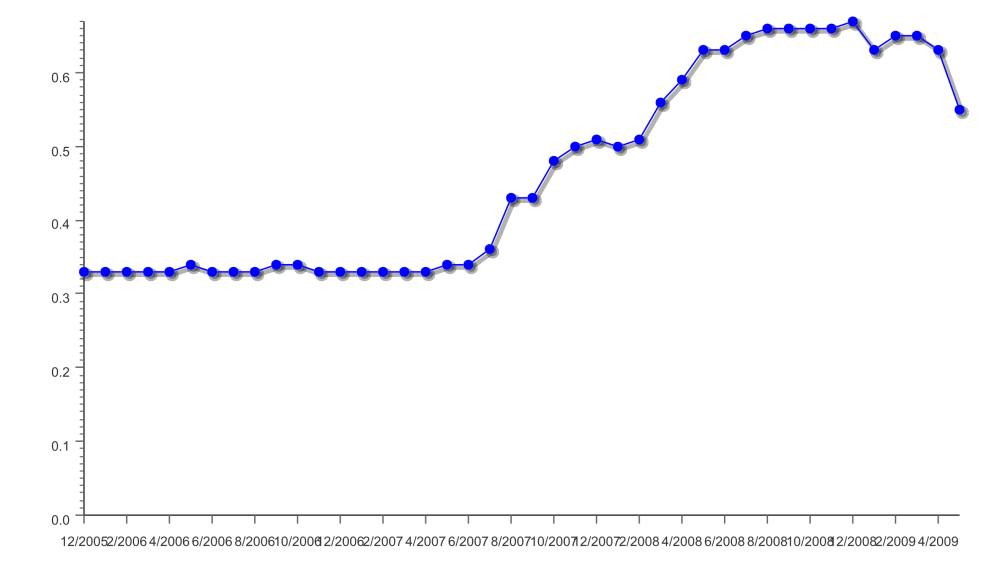

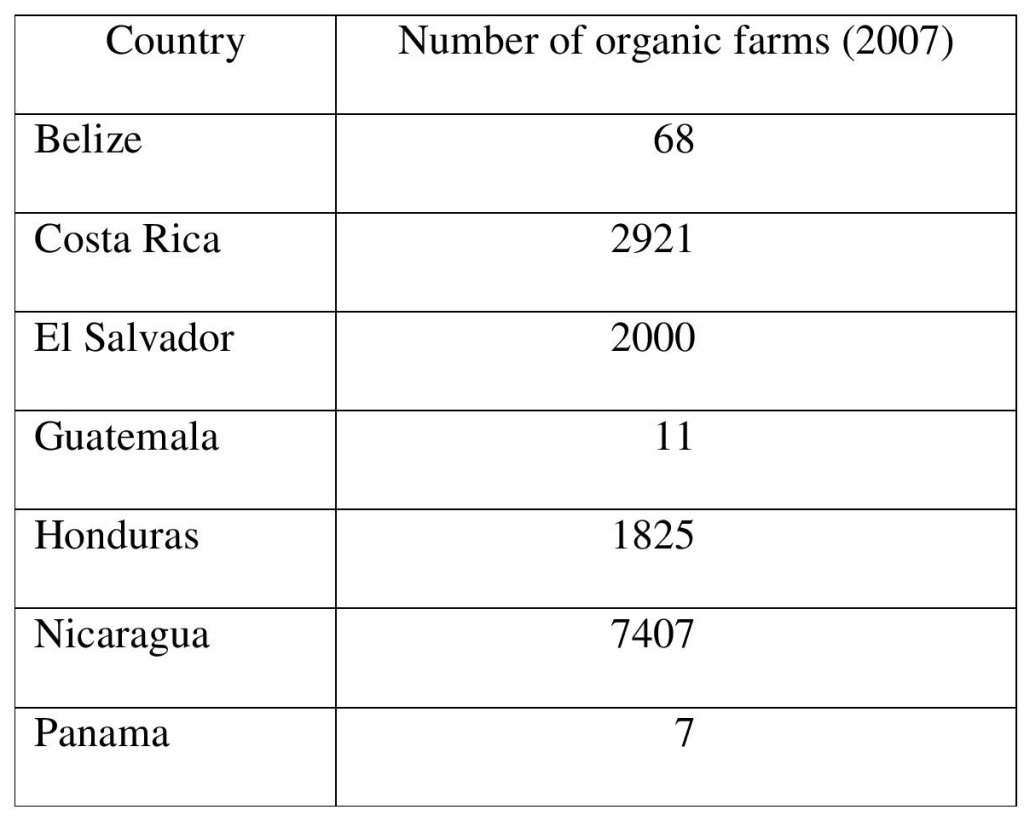

Number of organic farms in Central America, 2008

This figure is referred to in the book as Table 2.1 (Page 38)

Source: World Resources Institute, ‘Earth Trends’, http://earthtrends.wri.org