Activista señala que desarrollo continuo de megaproyectos hidroeléctricos agrava el cambio climático.

Por Vinicio Chacón, Semanario Universidad (Costa Rica) | vinicio.chacon@ucr.ac.cr

Sep 21, 2016

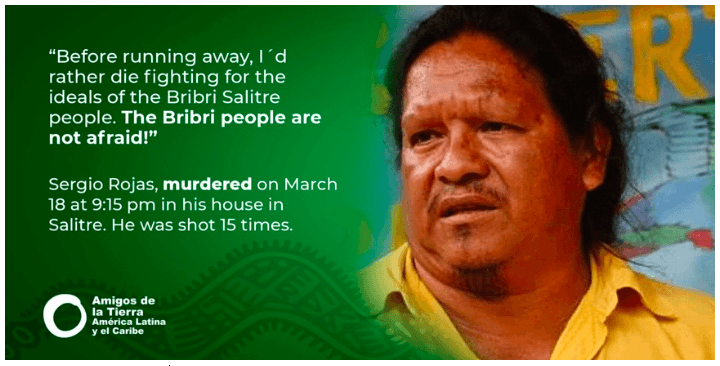

Palabras claves: Berta Cáceres; COPINH; criminalización; hidroelectricidad; cambio climático; Protocolo de Kioto; tratados de libre comercio.

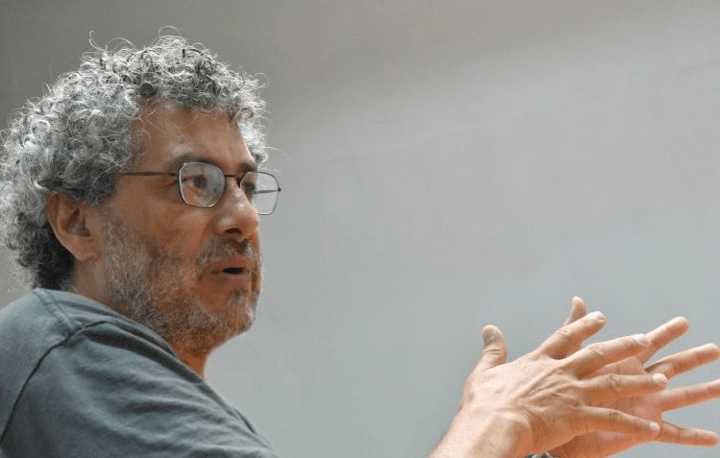

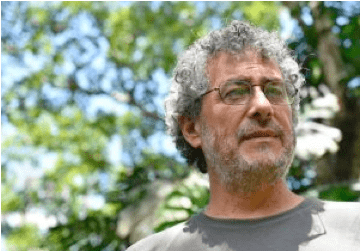

El ecologista mexicano Gustavo Castro ganó notoriedad por ser el único testigo del asesinato de la líder indígena y ambientalista hondureña Berta Cáceres, el pasado 2 de marzo [2016].

Castro es dirigente de la organización Otros Mundos – Amigos de la Tierra y con calma pero con contundencia abordó el asesinato y la increíble manipulación del caso que hizo el sistema judicial hondureño, buscando inculpar a activistas del Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras (COPINH).

Desde esa organización, Cáceres lideró la lucha del pueblo indígena lenca contra el proyecto hidroeléctrico (PH) Agua Zarca, de la empresa desarrollos Energéticos S.A. (DESA).

De vista en Costa Rica para participar en el II Congreso Latinoamericano sobre Conflictos Ambientales (COLCA), Gustavo Castro conversó con UNIVERSIDAD en una entrevista coordinada a través de la Federación Conservacionista de Costa Rica (FECON).

¿Cómo despertó su conciencia ecologista?

-Fue un proceso de muchos años de pasar en la participación en cooperativas, trabajé mucho tiempo con refugiados guatemaltecos que habían venido de la guerra. El salto a la lucha ambiental se da en la década de los 90, cuando empiezan a llegar al país muchos proyectos de inversión después del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte (ALCA), favoreciendo obviamente a las transnacionales y al saqueo del país.

-Eran de la nación el petróleo, el gas, el uso del agua, la electricidad, etc. No es que no habían conflictos, pero cuando pasan a manos de las corporaciones, exigen todavía más condiciones favorables de inversión. Empiezan a modificarse la ley de Aguas y la ley Minera para entregar a las grandes empresas mineras la explotación del oro, de la plata, de minerales estratégicos del país; ahora con la reforma energética, también el petróleo y el gas. Esto de alguna manera empieza a impactar cada vez más el medio ambiente, ahí empieza una lucha con mayor fuerza en torno a la defensa de los territorios; pero también cuando empezamos a ver la deforestación que causa la infraestructura para favorecer las inversiones, no solamente en mi caso, sino también en comunidades campesinas e indígenas empieza a haber una consciencia más grande sobre el impacto ambiental.

¿Cuándo se empiezan a dar los contactos con el COPINH y Berta Cáceres?

-A Berta la conocí en 1999, cuando empezamos a convocar muchos procesos de resistencia, entre ellos la creación de la Convergencia de Movimientos de los Pueblos de las Américas, el Encuentro Hemisférico Contra la Militarización, o el encuentro contra el Plan Puebla Panamá. Organizábamos todos esos encuentros en Chiapas; después los replicábamos en Honduras. Se hizo toda una relación en torno a los procesos de resistencia en los que participábamos no solamente nosotros y el COPINH, sino toda la región en Mesoamérica. Había mucha afinidad en el proceso de construcción del movimiento con Berta y el COPINH desde hace más de quince años.

¿Cuál es la lección más importante que se puede extraer de la historia de Berta Cáceres?

-Se me hace muy difícil decir una sola cosa, porque era una persona muy compleja, en el sentido de que era muy rica, una persona muy coherente que tenía la capacidad de análisis estructural; también podía tener una interlocución muy fuerte tanto con académicos como con congresistas, y al mismo tiempo estaba en la movilización con la gente.

-Fue sumamente respetuosa y muy tenaz, era una mujer muy valiente, siempre estaba al frente de todas las manifestaciones del COPINH. Berta fue muy coherente en su análisis, su discurso y su actitud con los pueblos y con el movimiento.

-Con el asesinato de Berta, su personalidad renace en todos lados. Como decimos, Berta no murió, se multiplicó, su presencia es muy fuerte.

-Fue una persona muy feliz, era muy optimista pese a todas las adversidades, ya que recibió muchas amenazas e intentos de asesinato.

Luego de perpetrado el asesinato y de que los sicarios le dieran a usted por muerto también, ¿qué actitud tuvieron las autoridades?

-Creo que lo primero que sorprende es que hubiera un testigo, que no esperaban. Llegué un día antes a La Esperanza (donde vivía Cáceres), entonces creo que nadie más que el COPINH y Berta sabía que yo iba a estar ahí. Me parece que pretendían que fuese un asesinato limpio, donde ella estaría sola en su casa. Cuando se dan cuenta de que hay un testigo, tienen que modificar el escenario y empezar a inventar ya la forma cómo criminalizar al mismo COPINH. No lo logran, entonces buscan cómo criminalizarme a mí.

-No pudieron presentarle a la familia, al COPINH y tampoco a la comunidad nacional e internacional una versión creíble, cuando había tantos antecedentes y estaba tan claro el origen del problema.

-Es por ello que de alguna manera intentan retenerme de manera ilegal en el país para buscar la forma en cómo imputarme. Al final a los que acaban sacrificando es al gerente de la empresa, al ejército y a los sicarios. Sabemos que no son los únicos que están involucrados.

-El trato que me daban era como de una ficha, como de objeto de prueba, violando mis derechos humanos pero también muchos procedimientos judiciales. Todo el mundo sabe porque en la prensa salió cómo se alteró la escena del crimen. En todos esos primeros días hubo muchísimas irregularidades en el proceso de investigación.

Incluso cuando hace el retrato hablado, el artista dibuja a otra persona.

Incluso cuando hace el retrato hablado, el artista dibuja a otra persona.

-Yo no sabía que mientras estaba en el Ministerio Público, habían detenido a un miembro del COPINH a quien intentaban culpar. Efectivamente, mientras yo estaba sin dormir, herido y con toda esa tensión, me traen a la persona que hace el retrato hablado. Yo le decía que así no era, lo borraba y volvía a dibujar lo mismo.

-Me dijeron en varias ocasiones que me podía ir. Yo obviamente estaba dispuesto a ayudar en todas las diligencias, aunque me tuvieran sin comer, sin dormir, sin una frazada si quiera; de cualquier manera yo iba apoyando, dejé mi ropa ensangrentada. Una forma como intentaron imputarme es que me robaron la maleta, que dejé en la casa de Berta, había obviamente la posibilidad de sembrar cualquier cosa que me pudiera inculpar – hasta la fecha no me la han entregado.

-No hicieron ninguna cadena de custodia aunque yo lo reclamé ante a fiscal, el Ministerio Público, la abogada de la Comisión de Derechos Humanos de Honduras, todo el mundo es testigo de que pedía copia de mi declaración ministerial y no me la daban – la copia de mi declaración ante la juez, y no me la daban; pedía que me regresaran mi maleta, igual. Era un cinismo de violación total al Código Procesal, al Código Penal, a los derechos humanos.

-Incluso no había una formalidad en el reconocimiento de las caras. Me pusieron al principio fotografías y videos del COPINH para que dijera si ahí estaba el culpable del asesinato.

-Se dan muchas irregularidades en este proceso y por ello el gobierno decreta que todas esas diligencias ministeriales se mantienen en secreto.

-En el caso del secuestro de Estado en el aeropuerto, me regresan otra vez a que hiciera más careos. Luego estuve en la casa del Embajador de México un mes, hasta el último día, sin que me dieran ninguna explicación de para qué me querían, sin que me entregaran incluso copia de la resolución de la juez donde decretaba mi prohibición de salir del país, y ante la insistencia de la abogada ante tal anomalía jurídica, tal ilegalidad, la juez suspende a mi abogada de su ejercicio profesional.

Posteriormente las autoridades relacionaron a funcionarios de la empresa DESA y de la institucionalidad militar con el asesinato, pero usted ha dicho que va más allá?

-No lo digo yo, lo dice la prensa, lo dice COPINH, lo dice la familia, incluso hubo un atentado contra un periodista que explicó muchas de las relaciones y vinculaciones de jueces y de políticos en el problema.

Ha afirmado que considerar la energía hidroeléctrica como limpia es una “estúpida idea”, lo cual es un gancho directo a la quijada del orgullo costarricense de producir energía de esa manera.

-No solamente en Costa Rica, sino en toda América Latina, que por décadas asoció siempre las hidroeléctricas con el desarrollo limpio.

-Si en Costa Rica no lo saben, que sepan que hay una resistencia impresionante en toda América Latina, de cantidad de pueblos que han sido desplazados y asesinados, que no ha habido una experiencia de reubicación adecuada ni tampoco de indemnización. Incluso la misma Comisión Mundial de Represas que financió el Banco Mundial, en el 2000 sacó un informe donde dicen que el 60% de las cuencas del planeta han sido represadas, que el 30% de los peces de agua dulce se han extinguido por causa de las presas que generan el 5% de los gases de efecto invernadero, que se han construido más de 50.000 grandes represas en el mundo, que los países quedaron sumamente endeudados con el Banco Mundial, que el 30% de las represas en el mundo no han generado la energía que debían generar, que desplazaron a 80 millones de personas en todo el mundo inundando pueblos y ciudad. Eso lo dice toda la evidencia en el mundo y en toda América Latina, en Chile, en Argentina, en Colombia, en Uruguay, en Panamá y en México hay resistencia contra las represas.

-A partir de ese informe el movimiento social contra las represas dijo “tenemos que desarticular ese discurso”, un discurso en donde hidroelectricidad es igual a energía limpia, cuando ha generado todos esos desastres, incluso desaparecido manglares, han desaparecido cuencas enteras por la construcción de represas.

-Con el Protocolo de Kioto vuelven otra vez a intentar reposicionar a las represas como energía limpia, en el sentido de que los países del Norte, para intentar reducir los gases de efecto invernadero, buscan suplirlo con inversión en energía limpia. Entonces si tengo que eliminar en el Norte diez toneladas de CO2, no lo elimino; mejor construyo una represa que según yo va a eliminar esas diez toneladas, las va a ahorrar en energía limpia.

-Los efectos de las represas en el mundo son desastrosos. ¿Cómo generar entonces otro paradigma de energía limpia? Ese es el gran problema; pero no construyendo, bloqueando más cuencas, desplazando más pueblos, lo que además favorece a las empresas constructoras de represas en todo el mundo. Hay otras formas y mecanismos de generar energía limpia. Incluso en Europa y Estados Unidos están desmantelando represas. Pero sí hay que construirlas en el Sur con la idea de que es energía limpia, sustentable y verde, pero es la energía más sucia que ha generado todos estos impactos socio-ambientales.

¿Están la mentalidad ecologista y ese nuevo paradigma para producir energía que usted menciona perdiendo el pulso contra la ideología extractivista, de la cual la construcción de represas es parte?

-Creo que más bien se está fortaleciendo mucho la resistencia. Incluso ha logrado detener muchos proyectos hidroeléctricos en Brasil, México, en muchos lugares.

-El gran reto que tenemos es cómo las mismas comunidades van construyendo alternativas distintas de desarrollo. Fui al COPINH como invitado para que reflexionáramos sobre otros modelos y mecanismos de generar energía limpia, autónoma, comunitaria que sirva a los pueblos, no inundando los territorios del COPINH para las zonas económicas especiales, para los proyectos mineros. Por ejemplo, la lixiviación del oro puede gastar según el tamaño de la mina, unos dos, tres millones de litros de agua cada hora. Necesitan represas y grandes cantidades de energía.

-El uso de energía y de agua se requiere para monocultivos, para parques industriales, para ciudades modelo, para incluso grandes centros turísticos, grandes hoteles, para la industria automotriz; y al final de cuentas los pueblos son los que pagan el precio de ese supuesto desarrollo.

¿Hasta qué punto todo ese proceso es impulsado por tratados de libre comercio? ¿Es realista esperar que los países denuncien esos tratados y se de espacio a un nuevo paradigma de generación de energía?

-Es un reto. La responsabilidad no es solamente de las poblaciones indígenas y campesinas de advertir y resistir a esto. Ciertamente los tratados de libre comercio aceleran este proceso y no solo los tratados, sino el supuesto Protocolo de Kioto.

-Los tratados de libre comercio abren las puertas a las inversiones: si antes no había diez parques industriales, ahora ya los hay y requieren agua y energía; si antes no había una empresa automotriz europea, japonesa, norteamericana en nuestro país, ahora ya hay tres, cuatro o cinco, y requieren agua y cantidades de energía. Si antes no había plantaciones de monocultivos y ahora sí, como Monsanto en zonas que requieren grandes cantidades de agua, pues ahora ya los hay. Si antes no existían proyectos mineros que requieren grandes cantidades de agua y energía, ahora ya los hay.

-Los tratados de libre comercio aceleran la necesidad de agua y energía, porque aceleran la inversión en todo este tipo de megaproyectos que requieren de estos insumos.

¿Está el acuerdo de París en la misma línea que el protocolo de Kioto?

-Sí, al final de cuentas no tocan de fondo el problema y siguen viendo la manera de cómo seguir dando paliativos, como pasó con el Protocolo de Kioto: quince años después lo aprueban, después de que se anuncia la urgencia, y aceptan reducir 5% el gas efecto invernadero no tras esos quince años, sino de quince años atrás – cosa que se pasa de absurda.

-Luego ese 5% ni siquiera lo voy a reducir; voy a buscar como lo compenso. Sigo produciendo toneladas de CO2 y mejor compro la selva de Costa Rica, los servicios ambientales, que respire diez toneladas. Entonces contaminación igual a cero: acá produzco diez, allá respiro diez; compro para respiración y le ponemos bonos de carbono o muy elegantemente economía verde.

-Lo mismo está pasando con todas las Conferencias de las Partes de la Convención Marco de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático (COP) que ha habido. No ha sido otra cosa más que ir posponiendo y posponiendo sin llegar al fondo del problema.

¿Cuál es el fondo del problema?

-Tenemos que cambiar el paradigma del sistema; tenemos que detener desde el origen el cambio climático y eso implica no solamente este capitalismo atroz, sino la contaminación que generan los países más desarrollados: entre el 60% y el 66% de los gases de efecto invernadero del planeta.

-Tenemos que detenerlo y como decía Berta, ya no hay tiempo. Dijo una frase muy bonita: “despertemos humanidad”. Creo que el problema es sistémico, es planetario y tenemos que tomar consciencia de la necesidad de cambiar este paradigma de desarrollo.

©2015 Semanario Universidad. Derechos reservados. Hecho por 5e Creative Labs, Two y Pandú y Semanario Universidad.

Reproducido aquí con permiso de Vinicio Chacón