The indigenous Naso people occupy a region of north-west Panama in the Bocas del Toro province, with a population of approximately 3,500. They live in 11 communities along the Teribe River and survive primarily as subsistence farmers. Their territory lies within two protected areas rich in biodiversity: the Palo Seco National Forest and La Amistad International Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site. They are one of the few remaining indigenous peoples in the Americas to have a monarchy recognised by the state.

Like many indigenous peoples, the problems faced by the Naso are rooted in their ongoing struggle for legal recognition of their traditional lands. The Naso people of the Bocas del Toro province in western Panama never enjoyed the benefit of Omar Torrijos’ 1970s designation of indigenous lands as comarcas within which they would enjoy a relatively high degree of autonomy and in which land could be held communally rather than individually. As a result, they have had to continue their struggle to retain their territory since the 1960s. According to Osvaldo Jordan of the Panamanian NGO, Alliance for Conservation and Development (ACD):

The Naso were unable to create sufficient public pressure for the creation of their comarca when the government still had a favourable opinion towards these autonomous territories. Now, the public consensus has turned against comarcas and the Naso are left trapped in this situation.[1]

Without official recognition of their comarca by the Panamanian government, the Naso stand in a weak position to defend their right to autonomy and self-determination. Without appropriate legal recognition and control over their territory, they feel unable to confront recent processes of acculturation and globalisation. Refusing legal title to the Naso territory constitutes a violation of the Naso’s rights according to the country’s constitution, as well as violating the American Convention of Human Rights. [2]

The Naso face two particular developments brought by the predominant Panamanian society. Both of these are especially crucial to the survival of their environment and their culture. The first of these is an ongoing battle with a cattle ranching company; and the second concerns the construction of the Bonyic dam and access roads to it.

Land conflicts between the Naso and the livestock company Ganadera Bocas are ongoing and have often turned violent. The disputed land is claimed by the Naso on grounds of ancestral ownership, whilst Ganadera Bocas possess a property title stating legal ownership since 1962.[3] Felix Sánchez, President of the Naso Foundation, explains the origins of the land ownership conflict:

“the Standard Fruit Company at that time [early 1960s] were the bosses, but at the same time they were not the owners; they were the nation’s tenants and not the legitimate owners. But afterwards in the seventies, the company went up for sale as a business, changing its name to one which had possession of the land amidst a pile of rules and arrangements which they made. That’s when it all started happening.”[4]

The Naso see this supposed ownership of their land by Ganadera Bocas as false and as having been conjured up by lawyers years ago rather than by any legitimate purchase. The conflict this has caused is still being played out on the ground today.

On 30 March 2009, police and employees of Ganadera Bocas entered the Naso villages of San San and San San Druy with heavy machinery, destroying 30 homes and the Naso Cultural Centre, the construction of which was only completed the previous day. Protests continued throughout 2009 and 2010, with a Naso camp based in Panama City, demanding that the government grant them the right to live on their land.[5]

In September 2009, the local mayor of Changuinola attended a meeting of the residents of the Naso village of San San Druy with King Valentín Santana and other Naso leaders in attendance.[6] This was an amicable meeting with considerable sympathy and empathy between the mayor and the residents. But two months later on 19 November 2009, the police moved in again and allowed the Ganadera Bocas company to enter with their machinery to destroy the village for a second time that year.[7] The photograph collage that follows this text illustrates a little of the Naso’s experience at the hands of Ganadera Bocas.

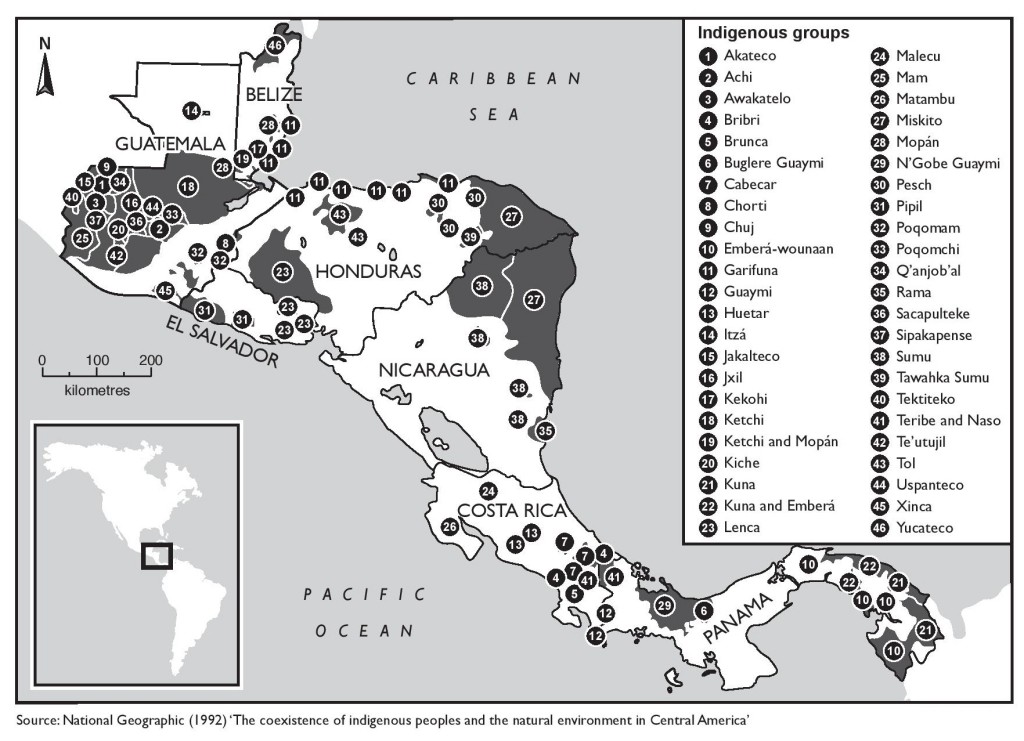

Indigenous comarcas of Panama

This struggle has not been helped by a division within the Naso people between King Valentín Santana and King Tito Santana. Interviews with Felix Sánchez and with King Valentín and the recording of the meeting with the local mayor made it crystal clear that the people of San San Druy community saw only King Valentín as their valid representative. Moreover, the villagers of San San Druy overwhelmingly saw Tito Santana as corrupt, having accepted money from Ganadera Bocas and having deserted the village. Doña Lupita from San San Druy, for instance, said: “King Tito says that he is the true king, but he is the government’s king. We recognise Valentín Santana – he is our king because he [Tito] has left the community. … We don’t recognise Tito as king because he is selling us out.”[8]

The second of their major battles is against the development megaproject of the $51m Bonyic hydroelectric dam, sponsored by Empresas Públicas de Medellín (EPM) which has a 75 per cent controlling stake in the Panamanian generating company Hidroecológica del Teribe (HET), the company which is building the hydroelectric plant.[9] The Bonyic dam is one of four planned in the Bocas del Toro province – known as the Changuinola-Teribe Dams – with a combined estimated capacity of 446 megawatts, equivalent to 30 per cent of Panama’s total production in the year 2004.[10] However, as with most development projects, the costs and benefits are rarely equitably distributed and the Naso may stand to lose more than they gain.

The Bonyic project has caused yet more rifts within the Naso people. Their former king Tito Santana collaborated with EPM, keen to embrace the advantages of modernity and development, including the offer of a school, clinic, jobs, infrastructure and university scholarships. His support for the project provoked a revolt and he was forced into exile in 2004, with his uncle Valentín Santana assuming his position, backed by opponents of the project. The government, however, continues to recognise Tito as the legitimate king. As Rory Carroll commented in the Guardian “the discord reflects an anguished debate about Naso identity and the balance between heritage and modernity”. [11]

Supporters of King Valentín Santana doubt that benefits will compensate for the environmental and social costs of the dam, and maintain that the project will destroy their cultural and natural heritage. A new highway is planned to connect the population of the large town Changuinola with the dam, which will undoubtedly bring radical changes to their lives including migration. The testimony of some of the Naso opponents to the project is given in The testimony of the Naso given in the interviews section of this website includes the words of Alicia Quintero whose land stands in the way of the proposed road.

The project received an early setback in 2005 when the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) rejected an application to finance the dam, its rejection being at least partly based on the inadequate environmental impact assessment. This represented a clear victory for the Naso opponents, but funding was raised by HET from private sources and construction began in 2007. Since construction work began, human rights abuses of the Naso have also taken place, these including the detention of fourteen Naso people and sexual assaults of Naso women. Additionally, local police officers work as armed security guards for the development during their out-of-work hours; the Panamanian environment ministry granted to the developer the right to administer land that belongs to the Naso; and clearance and construction work along the valley began illegally in February 2009 before the Panamanian government gave permission for it to do so, which they did in March 2010.

On 30 November 2009 the Naso resistance movement reported on the ongoing struggles. Extracts from their communication are given below.

Naso leaders of the San San Druy and San San communities have accepted the establishment of a round table of negotiation with the government on a possible comarca and under the coordination of the President of the Commission of Indigenous Affairs, Leopoldo Archibold. The proposal was accepted this morning in a meeting with the Indigenist Policy Group and the Vice-Minister of Government and Justice and to which the executive invited the illegitimate King Tito Santana, dismissed by the community and an habitual associate of Empresas Públicas de Medellín and Ganadera Bocas. The round table starts work on 11 December and is made up of 10 delegates of the legitimate King Valentín Santana and 10 of Tito Santana. Although these accords have been reached, the Minister of Government and Justice, José Raúl Mulino, insisted on calling the residents of San San Druy and San San ‘squatters’, and likewise his director of the Indigenist Policy Group, José Isaac Acosta, was contemptuous of the community, insinuating that they are incited by NGOs and foreigners. The Naso leaders accepted the round table although without much hope of reaching a good solution given the repeated failure of the government to comply with the most basic accords which have been reached over the previous eight months.[12]

On 10 December 2009, a day before the planned meeting, with no explanation, the government unilaterally suspended the round table planned for the following day. Comuna Sur reported that

… theoretically, the purpose of the meeting was to begin discussions about the creation of a new Naso comarca. However, following the pattern of recent months, everything has been suspended without any convincing reason and without a new date. So the Naso communities of San San Druy and San San continue to re-build their houses on the land in conflict under the view of private security agents. According to the director of the Indigenist Policy Unit in Panama, there is no conflict with the indigenous people. In this way, they try to make them invisible so that they cease to exist. But the communities in resistance constantly remind themselves that their rights are being denied.[13]

Opponents of the Bonyic project include more than just the Naso people. In 2010 the international heavyweight organisation IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) and the World Heritage Centre reported their concern about the impacts of all four proposed dams:

The World Heritage Centre and IUCN conclude that it will likely be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to adequately mitigate the habitat loss and fragmentation effects of the proposed dams on the property’s freshwater ecosystem, and that the possible secondary and cumulative effects of eliminating up to 16 migratory aquatic species within portions of the property may significantly affect predatory bird and mammal populations. Until the State Party of Panama investigates alternatives to the four proposed dams through a detailed transboundary Strategic Environmental Assessment process, the World Heritage Centre and IUCN recommend that all dam construction be halted to safeguard the property’s values and integrity.[14]

The International Rivers Network has also demonstrated major holes in the preparation and arguments in favour of the Bonyic dam and in the company’s underhand tactics to gain Naso approval for the project.[15] The Global Greengrants Fund has also lent its weight in support of those who oppose the project.[16] The Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF) website has a HydroCalculator tool which can be used to estimate basic economic feasibility analyses of hydro-electric projects as well as summarising their social and environmental costs. For instance, their calculator produces a statistics for the number of displaced persons per megawatt of electricity produced. From their analysis of the four Changuinola – Teribe Dams, they conclude that “the projects would most likely be both economically and financially feasible. Nonetheless, they would cause environmental damage in an area of global conservation interest and impose serious hardship on indigenous communities living along these rivers.”[17]

Most Third World governments serve as agents of the prevailing economic model of development, and in that role they are keen to capitalise on the income potential represented by natural resources within their national boundaries. Exploitation of natural resources such as mineral wealth, timber, plant diversity, hydroelectric energy and even wildlife has proven easy to exploit if destruction of the natural environment and removal of its inhabitants can be disregarded. And some Central American governments have indeed managed to disregard the natural ecosystems in their ‘development’ of natural resources whilst at the same time waxing lyrical about the need to protect the environment.

[1] Personal communication

[2] Environmental Defender Law Center http://www.edlc.org/cases/communities/naso-of-panama/2/ (accessed 16 July 2009)

[3] http://mensual.prensa.com/mensual/contenido/2009/05/31/hoy/panorama/1803560.asp (accessed 16 July 2009)

[4] Felix Sánchez interviewed for this book, San San Druy, Panama, 1 September 2009.

[5] http://mensual.prensa.com/mensual/contenido/2009/07/06/hoy/panorama/1844317.asp (accessed 16 July 2009)

[6] The meeting in San San Druy on 1 September 2009 was recorded for the purposes of this book, and the quotes from Naso residents and leaders which appear in this chapter are taken mainly from this recording.

[7] Karis McLaughlin and Martin Mowforth (December 2009) ‘For the second time this year the Naso have their houses destroyed to make way for a cattle ranching company’, ENCA Newsletter No. 49, Environmental Network for Central America, London.

[8] Doña Lupita in meeting with Mayor of Changuinola, Panama, in the village of San San Druy, 1 September 2009.

[9] OneMBA (6 November 2003) ‘EPM pagará US$6,6mn por Teribe’, www.bnamericas.com/news/energiaelectrica/EPM_pagara_US*6,6mn_por_Teribe (accessed 15.06.11).

[10] Cordero, S., Montenegro, R., Mafla, M., Burgués, I., and Reid, J. (2006) ‘Análisis de costo beneficio de cuatro proyectos hidroeléctricos en la cuenca Changuinola-Teribe’, The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (July).

[11] Rory Carroll, ‘Hydro plant splits jungle kingdom as tribe feels damned by new way of life’, The Guardian, 16 June 2008

[12] http://resistencianaso.wordpress.com

[13] Comuna Sur (2009) ‘Gobierno de Panama falta una vez más a sus compromisos’, email communication, 10 December 2009

[14] World Heritage Centre and International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) (2010) ‘State of conservation of World Heritage properties inscribed on the World Heritage List’, WHC-10/34.COM/7B, p.86.

[15] Payal Parekh (2010) ‘Comments on the Bonyic Hydroelectric Project (Panama)’, International Rivers website: www.internationalrivers.org/panama/comments-bonyic-hydroelectric-project-panama (accessed 14 June 2011).

[16] Global Greengrants Fund (1 August 2006) ‘Panama: Fighting Hydroelectric Dams’, www.greengrants.org/2006/08/01/panama-fighting-hydroelectric-dams/ (accessed 14 June 2011).

[17] Tathi Bezerra (24 March 2009) ‘Changuinola – Teribe Dams in Panama’, Conservation Strategy Fund website: http://conservation-strategy.org/en/project/changuinola-teribe-dams-panama (accessed 14.06.11).