By Jennifer Kennedy* on August 27, 2013 | Intercontinental Cry Magazine | Reproduced by kind permission of Jennifer Kennedy

A critical situation is developing in Naso territory, Bocas del Toro province, Panama. Some 50 Naso protesters are blockading the access road to the Boynic hydroelectric project, preventing workers from entering the construction site of the 30 megawatt dam, which is scheduled for completion later this year.

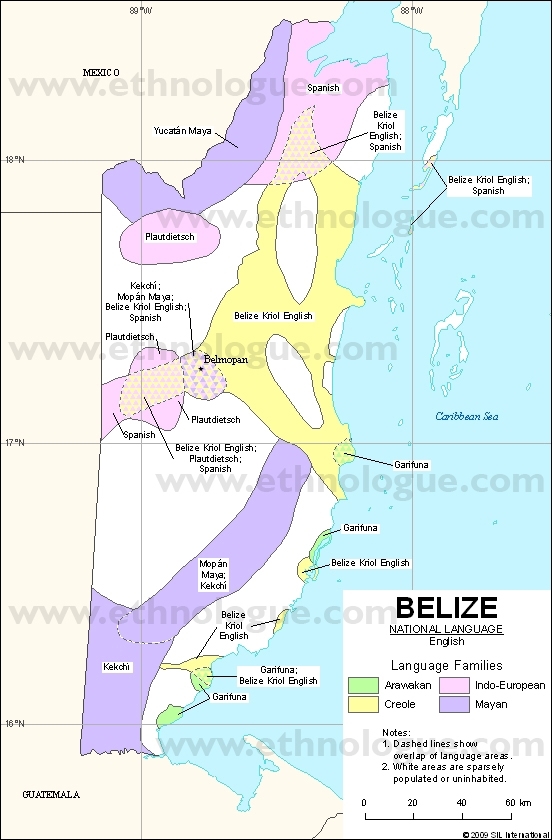

Picture by Jennifer Kennedy

The protesters are demanding the government ratify an agreement that was made two weeks ago, on Aug. 14, 2013. According to Panama’s national newspaper La Prensa, attendees at the meeting, held in the Naso capital, Sieiyik, discussed issues such as the right to a comarca (a semi-autonomous region), future hydroelectric projects in the area, and current projects the king has negotiated without community consultation.

A resolution came out of the meeting, calling for King Alexis Santana to renounce the throne, new elections to be held, and the revocation of compensation agreements made with Empresas Públicas de Medellín (EPM), the Colombian company constructing the project.

The King was told he had 48 hours to leave the royal palace in Sieiyik, and the meeting turned violent when one of the attendees, Luis Gamarra, was attacked by the spokesman of the board of the king, Adolfo Peterson.

Although notified, neither national nor local government officials attended the meeting.

The road closure is indefinite say protesters, who insist that the agreement must be ratified by the government. They are now waiting for the Minister of Government, Jorge Ricardo Fabrega, to meet with them.

In a statement announced over the weekend, EPM said the blockade is affecting 3 thousand families who benefit from the project. Elizabeth Sanchez, a local leader, told La Prensa she is unhappy that a small group of people are threatening a workforce of some 600 Naso.

The project has been controversial since its inception.

In 2005, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) decided against funding the project after considering the environmental and social impacts.

A year later, the Naso made international news when the former king, Tito Santana, made a deal with EPM to build the dam on the Bon River in the heart of Naso territory. Tito divided the nation of some 3000 people when he failed to consult with them. Tito was exiled to the nearby town of El Silencio and his uncle, Valetin, replaced him as king. The government refused to recognize the staunchly anti-dam Valetin and in 2011, another election took place and Alexis Santana, who also opposed hydroelectric projects, was voted in.

In September 2012, protests erupted and the road closed. Several Naso were dismayed at the destructive way in which EPM was proceeding. Others were fed up of waiting for promised compensations. Faith in the new king began to wane.

Talking to the US-based NGO Big River Foundation in July, Edwin Sanchez, and a leader with the Organization for the Development of Sustainable Eco-tourism for the Naso (ODESEN), said “Promises are not being kept and the company is expanding in our territory. What our ancestors left us is going to be lost. They left us this land for us to care for. We expect our King to give us the support we deserve.”

The Naso are one of the few indigenous groups in the Americas that continue to have a monarchy, and this small nation, which is spread across 11 riverside communities, has relied upon and protected the surrounding rainforest and its rivers for generations. Cultural traditions include fishing, hunting, traditional medicine, and bush craft, but their culture, like their land, is under threat.

Bordering the UNESCO World Heritage Site, La Amistad International Park (PILA), which Panama co-manages with Costa Rica, Naso territory is also of ecological importance.

PILA was deemed to have ‘outstanding universal values’ because of its high biodiversity. But ongoing hydroelectric development is threatening the park. In UNESCO’s 37th World Heritage Committee in July, it regretted that Bonyic’s construction continued without considering the results of the on-going Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). UNESCO also noted with concern the permanent damage to fresh water biodiversity in the Bonyic watershed and “the absence of adequate measures to mitigate for biodiversity loss…”

In January, UNESCO sent a monitoring mission to PILA to assess various threats to the park, such as ongoing dam development and potential hydroelectric projects. One of the comments in the mission report focused on the immense social impact that dams are having upon communities like the Naso.

“The social conflicts related to the hydropower construction (and even before, in the feasibility stage) have changed many parts of the traditional lifestyle, damaged internal relationships and threatened the interaction of men with the environment (through displacement and new immigrations).”

The Naso are particularly vulnerable. Unlike many other Indigenous Peoples in Panama, their territory has never received official status as a comarca. James Anaya, the Special Rapporteur for Indigenous People, visited Panama in July and in his concluding declaration on the rights of indigenous people in Panama he stated that “of particular concern is the territorial insecurity of the Bribri and Naso whose territories do not have comarcal recognition.”

Promises of a comarca have been made often but never fulfilled.

Luis Gamarra, a community leader, told the Big River Foundation in July that according to the Commission of Indigenous Affairs in Panama, “no authority has ever submitted any petition for the region for the law creating the Naso County 19.” Adolfo Villagra, an ODESEN leader who runs the Naso eco-lodge, WEKSO, also told Big River Foundation that the government was refusing to give the Naso their land for political reasons. He said they will not rest “until the Naso community has a comarca…”

* Jennifer is a freelance journalist writing about human rights, hydroelectric development, the extractive industries and corporate malfeasance in Latin America, Africa and the UK.

jenniferjkennedy.com