This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Category: Chapter 8

The Ngöbe-Bugle and dam projects on the Río Changuinola

Whilst the case of the Naso (against a combination of big business and the Panamanian government) is rather disheartening at present, the struggles and campaigns of indigenous groups, even in the same region as the Naso, are not all in vain, as the campaign of the Ngöbe-Bugle against the construction of a dam for hydro-electric power production is showing. But all is not quite as it may appear from the hopeful note struck by the headline of the next article, for the government of Panama has chosen to ignore the ruling of the IACHR and to go ahead with the construction regardless.

We are grateful to Peter Galvin for permission to reproduce his article (as follows) which was first published in June 2009 – http://intercontinentalcry.org/major-victory-for-the-ngobe-of-western-panama

Panama’s Ngöbe Indians Win Major Victory at Inter-American Commission on Human Rights: Dam Construction Ordered Halted

By: Peter Galvin

WASHINGTON— After two years of brutal government repression and destruction of their homeland, the Ngöbe Indians of western Panama won a major victory yesterday as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights called on Panama to suspend all work on a hydroelectric dam that threatens the Ngöbe homeland. The Chan-75 Dam is being built across the Changuinola River by the government of Panama and a subsidiary of the Virginia-based energy giant AES Corporation.

The Commission’s decision was the result of a petition filed last year by the Ngöbe after AES-Changuinola began bulldozing houses and farming plots. When the Ngöbe protested the destruction of their homes, the government sent in riot police who beat and arrested villagers, including women and children, and then set up a permanent cordon around the community to prevent anyone from entering the area. In addition to threatening the community, the dam will irreversibly harm the nearby La Amistad UN Biosphere Reserve.

The Commission’s decision was the result of a petition filed last year by the Ngöbe after AES-Changuinola began bulldozing houses and farming plots. When the Ngöbe protested the destruction of their homes, the government sent in riot police who beat and arrested villagers, including women and children, and then set up a permanent cordon around the community to prevent anyone from entering the area. In addition to threatening the community, the dam will irreversibly harm the nearby La Amistad UN Biosphere Reserve.

“We are thrilled to have the Commission take these measures to protect Ngöbe communities,” said Ellen Lutz, executive director of Cultural Survival and lead counsel for the Ngöbe. “We are hopeful that this will help the government of Panama and AES recognise their obligation to respect Ngöbe rights.”

The Commission, which is a body of the Organisation of American States, is still considering the Ngöbe’s petition and issued this injunction, called precautionary measures, to prevent any further threat to the community and the environment while the Commission deliberates on the merits of the case.

Specifically, the Commission called on the government to suspend all construction and other activities related to its concession to AES-Changuinola to build and administer the Chan-75 Dam and abutting nationally protected lands along the Changuinola River.

In addition to Chan-75, for which land clearing, roadwork, and river dredging are already well underway, the order covers two other proposed dam sites upstream. The Commission further called upon the government of Panama to guarantee the Ngöbe people’s basic human rights, including their rights to life, physical security, and freedom of movement, and to prevent violence or intimidation against them, which have been typical of the construction process over the past two years. The Commission required the government to report to it in 20 days on the steps it has taken to comply with the precautionary measures.

Chan-75 would inundate four Ngöbe villages that are home to approximately 1,000. Another 4,000 Ngöbe living in neighboring villages would be affected by the destruction of their transportation routes, flooding of their agricultural plots, lack of access to their farmlands, and reduction or elimination of fish that are an important protein source in their diet. It would also open up their territories to non-Ngöbe settlers.

The dam also will cause grave environmental harm to the UNESCO-protected La Amistad Biosphere Reserve, an international World Heritage Site that is upriver from the dam site. Scientists believe that there is a high risk of losing important fish species that support the reserve’s wildlife, including several endangered species, because the dam will destroy their migration route.

“The Panamanian government must follow the precautionary measures issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and prevent further human-rights violations and environmental damage,” said Jacki Lopez, staff attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, an organisation that submitted an amicus curiae to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in support of the Ngöbe.

The Ngöbe people’s situation was the subject of a report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People, James Anaya, made on May 12, 2009. Anaya concluded that the government ignored its obligation under international law to consult with the communities and seek their free, prior, and informed consent before moving ahead with the construction project. He urged AES-Changuinola to meet international standards for corporate social responsibility and not contribute, even indirectly, to violations of human rights.

Further information can be sought from the author, Peter Galvin at pgalvin@biologicaldiversity.org

Partner Organizations:

Centre for Biological Diversity – www.biologicaldiversity.org

Cultural Survival – www.culturalsurvival .org

International Rivers – www.internationalrivers.org

La Alianza para la Conservacion y Desarrollo – www.acdpanama.org

Global Response – www.globalresponse.org

It is interesting that this article generated some critical comments from proponents of the Chan-75 dam. These were based largely on the grounds that energy generation is for the whole of Panama’s population, that the general benefit is greater than the disbenefit to the Ngöbe-Bugle, and that hydro-electric power generation is much more acceptable on environmental grounds than fossil fuel power generation. But as one respondent to these critical points answers, “What’s the point of [passing] legislation [in favour of indigenous groups] if the government isn’t going to obey it?”

National languages of El Salvador and Honduras

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Damming the Ngäbe: Aftermath of an AES Power Project in Panama

by Jennifer Kennedy* | October 15th, 2012 | Reproduced by kind permission

Luis Abrego, a Ngäbe boatman, navigates the vast man–made reservoir that now covers four indigenous communities with a sea of murky water and rotting debris. Raising his eyes from the struggle to steer through the dead trees and decaying logs that clank against his boat, Abrego catches sight of an imposing concrete dam. Chan 75 is one of the latest and most controversial projects in Panama’s rapidly expanding portfolio of hydroelectric plants.

In recent years, Panama’s economy has grown exponentially, and lacking domestic oil, the small Central American country has looked to hydroelectricity to fill its increasing energy needs. Hydro power now constitutes approximately 54 percent of Panama’s total energy. By aggressively exploiting Panama’s rivers, the government plans to create more than 80 new hydro projects by 2016.

On July 9, Panamanian President Ricardo Martinelli, formally inaugurated AES Corporation’s Chan 75 (also known as Chan I) hydroelectric dam. Jonathan Farrar, the U.S. ambassador to Panama, heralded the project as an “impressive demonstration of how sustainable development can work in Panama.” Throughout the country, colorful television commercials and catchy radio tunes reiterate AES’s commitment to “social responsibility.” But the displaced Ngäbe who live in the mega project’s wake have a different narrative.

“I was in the house when they started to close the [dam] gates, and they didn’t tell me anything. It surprised all of us,” said Santos Morales, a Ngäbe elder and a former resident of Guayabal. Morales, a thin man with a guarded expression, is one of several people whose homes and land were flooded when AES inundated the area in June 2011. He opposed construction of the dam, but when it became clear that not even international outcry could prevent completion, he tried to negotiate with AES for compensation. When these efforts failed, he and several others remained on their land until the water began to rise.

Carolina Tera, his sister, was also forced to abandon her house. “I have lost everything,” said the defiant elder, as she sat in a family house, several miles from her former home, which is now half submerged in rotting vegetation and stagnant water.

“They [AES] have taken everything from me,” explained Tera in her native Ngäbere language, her voice strong and indignant.

AES in Panama

AES Corporation, a U.S. based power company headquartered in Arlington, Virginia, generates and distributes energy in 27 countries and has a global workforce of approximately 27,000, according to its website. Founded in 1981 by Roger Sant and Dennis Bakke, AES has an annual revenue of $17 billion and manages $45 billion in total assets. It is one of the world’s largest energy companies.

AES began investing in Panama in 1999 with the creation of its subsidiary, AES Panama, and is now the country’s leading U.S. investor. Its five hydroelectric projects produce 35 percent of the nation’s energy.

In 2007, the Panamanian government awarded a concession to AES subsidiary, AES Changuinola, to build Chan 75 – a 233 megawatt dam on the Changuinola River in Bocas del Toro Province, which borders Costa Rica in western Panama. From the outset, affected community members accused AES Changuinola of using coercion, bribery and intimidation.

In March 2008 a group of community members submitted a 25 page petition to the Inter–American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) detailing the abuses – with the aid of the Alliance for Conservation and Development (ACD), a Panama City–based environmental non–governmental organization (NGO), and Cultural Survival, a U.S. based NGO working for indigenous rights worldwide.

James Anaya, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People visited the communities on May 12, 2009. As a result of his November 2009 report, the IACHR asked the government of Panama to order the suspension of construction pending further investigations. The government ignored the request, and the $600 million project was completed in 2011. Chan 75 displaced 1,000 people and 180 Ngäbe families.

The Ngäbe

The Ngäbe, Panama’s largest indigenous group, number approximately 200,000. Some 40 percent live in communal lands, including in territories inside the Palo Seco protected forest, where Chan 75 is located. They have lived a nomadic life in the Changuinola River region of western Panama for thousands of years before Spanish colonization. In the 1960s, owing to land pressures in other parts of Bocas del Toro, Ngäbe families began settling on ancestral land “owned” in common, and never formally demarcated or deeded.

Traditionally, most Ngäbe are subsistence farmers with a strong dependence on the land and a very limited cash economy. Rivers like the Changuinola – used for transportation, fishing, agriculture, and drinking water – are the communities’ lifeblood. After the dam flooded the region, displaced Ngäbe lost both use of the river and some of their best cultivable land.

Eliminating a Community

It has now been more than a year since the inundation, and Tera and Morales still have not reached a compensation agreement with AES-Changuinola. AES, after declining a live interview, sent CorpWatch a fact sheet stating that, “AES Changuinola committed to start filling the reservoir only after all families had left the area.”

AES offered compensation, but the Santos family refused, stating that the proposed settlement did not take into account how long they had cultivated their land, or how it would have sustained them for generations to come.

Morales and Tera say they are also skeptical of AES because it has not kept agreements it negotiated with other family members. “They promised land transport, water transport, and housing, but they haven’t completed any of it,” said Morales. “To this day we haven’t observed any housing constructed in [Guayabal]. They say they’re building it, but it’s completely false.”

AES guaranteed that it would replace the communities – Valle del Rey, Changuinola Arriba, Charco la Pava and Guayabal – that Chan 75 destroyed, and build four new settlements with “dignified” new houses for the displaced. AES Changuinola’s website features a color poster dating from 2008, which illustrates how the new resettlements were supposed to look – including sports areas, schools, and community centers – by the completion date in 2011.

It now appears that AES is constructing three communities, not four. Asked in a September 24 email about the promised construction of Guayabal, Rich Bulger, AES vice president of external communications, wrote that, “as a result of the process, encouraging community participation, some families chose to move to only 3 of those new communities (to clarify, Guayabal included a number of farms and not permanent housing). Others chose to stay at their current houses in the nearby community of Valle Risco.”

In fact, at least 27 families lived in Guayabal, and the Alliance for Conservation and Development refutes the claim that the families decided to live in other communities.

According to community members and ACD, none of the new sites are yet complete. (This reporter was unable to document all the resettlement sites because of security restrictions, but some construction was evident in Charco la Pava, the nearest settlement to the dam itself.)

Contract with Police

The 2008 IACHR petition reported that AES used deception and coercion from 2006, before the concession was granted, to get community members to sell their land: ‘using the prospect of large sums of money and the threat of forced evictions, AES–Changuinola has lured heads of families, many of whom do not speak Spanish or are illiterate into signing documents that purportedly give rights to AES–Changuinola … Many Ngöbe who initially refused to sign contracts with AES were harassed or bullied by the company and state and local government officials into doing so.’

The community began to organize protests in early 2008, with some 300 Ngäbe rallying to block the project’s access road in Charco la Pava. According to IACHR petition, “the peaceful protest was met not only with arrests, but also with police violence.” An article in the Spring 2008 edition of Cultural Survival Quarterly reported that police “broke the nose of a nine year old boy and injured his sister’s arm. They knocked down and sexually humiliated a woman carrying a three year old child on her back.”

In March 2008, AES entered into a contract with the national police. According to a 2008 government communication sent to the UN Special Rapporteur, the contract was established, “to guarantee peace and security in the community and the area of construction.” A November 2010 Cultural Survival report for the Universal Periodic Review Working Group (UPR) reported that, “since [March 2008] policemen hired by AES have illegally restricted movement in and out of the district (confirmed by a study participant in March 2010).”

Today, the police presence is gone but journalists are still restricted from visiting the area. Ngäbe guides helped arrange a covert visit for me on August 6.

On that trip I interviewed three Charco la Pava residents, Macaria Acosta, Luica Sanchez, and Luis Abrego. Acosta sat in the house her family was building, surrounded by construction work, and perched high on a hill backed by forest and overlooking the reservoir. “We are waiting on the money that [AES] promised us, but we haven’t received anything, and I don’t know what to do,” she said.

Negotiating in Bad Faith

Lucia Sanchez, another Charco resident, told CorpWatch how Samuel Carpintero, a Ngäbe lawyer, convinced her in 2008 to negotiate with AES. “He promised he was going to help us, and make life easier… but it hasn’t been easier,” she said. “I don’t have any food, a house; we don’t have good bathrooms. We don’t have anything.”

Carpintero – who previously participated in the United Nations Indigenous Fellowship Program – lived and worked in the area from about April 2008 to November 2009, according to Osvaldo Jordan, director of ACD. During this time Jordan claimed that a “change” took place, and in November 2009, leaders from Charco, Valle del Rey, and Changuinola Arriba, who had been initially against the project, signed agreements with AES.

These leaders, according to AES’s fact sheet, represent their communities at a “High Level Commission” created in August 2009, “to address the requests related to the resettlement process made by the communities near the Changuinola hydro project.”

However, Luis Abrego, like others I spoke to, claimed that AES is negotiating with leaders who do not represent all those affected.

According to a 2009 shadow report that ACD submitted to the United Nations Committee of the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, “instead of conducting open meetings with the communities according to Ngäbe customs, government officials and AES representatives have been conducting backroom negotiations with a reduced number of community representatives.”

In July 2010, Charco community leaders, who had signed accords with AES in 2009, registered a Panamanian company, the Ngäbe Lake Development and Environment (DANG). Carpintero is listed as a DANG subscriber – someone who has an agreement to purchase stock in a privately held corporation.

AES contracted DANG to build the resettlement communities and clean up the reservoir. However, there are allegations, based on dozens of testimonies collected by ACD, that DANG on AES’s behalf, is acting as a security force and that,“[DANG] have intimidated people, they’ve detained people, they’ve threatened people, and they destroyed farms.”

Acosta and Sanchez both charged that DANG has intimidated them. Indeed, on my first visit to Charco la Pava, June 30, a DANG worker escorted me to the house of Rafael Abrego, a community leader and a DANG director. Abrego angrily explained that it was his job to liaise with the government and AES before allowing any visitors into Charco la Pava. After detaining me for 30 minutes, he made me delete my photos of the area and ordered me to leave. When I quietly returned to the town in August the mood in Acosta’s house was somber, and one of the women said that DANG had threatened to withhold her compensation if she spoke to journalists.

Acosta said that DANG has her AES contract and she herself has no copy. “[AES] says that we’re living well, that we don’t need anything, but it’s a lie. It’s a pure lie.” Looking around nervously, Sanchez added that DANG told her “that ‘if anybody arrives here, tell them you’re well.’ But it’s all a lie.”

CorpWatch emailed a series of questions to AES about compensation, the corporation’s relationship with DANG, the role of Samuel Carpintero, and community members’ charges of intimidation of. AES has so far failed to address these questions.

The Reality Behind the Posters

The Becker family, one of the hundreds of Ngäbe whose land was destroyed by Chan 75, owned a substantial area of land in Charco la Pava where AES wanted to build the dam wall. The Becker family’s plight, detailed in the 2008 IACHR petition, was widely publicized by Cultural Survival.

In January 2007 AES was eager to begin construction. According to Isabel Becker, a widow in her 60s and the head of her family, AES flew her 620 miles to Panama City. Becker claims that she was held for several hours in an office until she signed a document, in Spanish. A Ngäbere speaker, she says she did not understand that she was signing a contract to sell AES her family’s land.

In October 2007, despite subsequent attempts to nullify the contract, the family claims that after months of pressure, they were relocated to nine new homes in Finca 4, a suburb of the city of Changuinola, an hour drive from Charco la Pava.

The Becker family features prominently in AES’s public relations campaign as “emblematic” examples of the company’s “participative resettlement program.”

Sitting in Becker’s concrete bungalow, Valencio Miranda translates for his grandmother. “The company said if you do not get out of here, we will bring the police, and they’ll throw you in jail.” Miranda explains: “That’s why my grandmother left. She was afraid. She cried, she cried, she shed tears for that land there.”

On AES Changuinola’s website, an advertisement from 2007 proclaims that Becker’s new house – and those for other family members – “will be better and more spacious.”

But the house that AES provided for his mother, Julia Castillo Miranda, was cramped and had no indoor toilet facilities or water. Miranda pointed to a partition wall that his mother paid for it in order to separate the rooms.

“There are no rooms where I can sleep. I sleep outside like a pig,” he said, crammed together with most of the 20 family members who live there.

Miranda told CorpWatch that since leaving Charco, life has been harder. He has no land to work, and despite AES’s promises to provide work, he is still unemployed.

“We cannot continue like this. Here we can go hungry for two days, sometimes one week. We have no money to buy anything. We need money to buy food.”

AES declined to comment on the allegation that families like the Beckers were “forced” to resettle.

Failure of Compensation Program

To date, the exact number of uncompensated or under compensated Ngäbe affected by Chan 75 is unknown. Pedro Abrego, a Ngäbe lawyer who has worked with the affected communities, said he was aware of at least 40 people who have received nothing from AES, along with another 100 who got only partial reparations. Jordan of ACD said that he believed that the majority of people who have signed agreements are still waiting. A special work group with UN participation is expected to give an updated number in a forthcoming review.

Others noted that the compensation provided so far will not support their families in the long term.

For example, AES claims in its fact sheet that it has developed a “farm improvement program,” but community members say AES has provided no new land, or pushed them into uncultivable or inaccessible areas boxed in by AES holdings. “The Ngäbe are trapped between the land that was flooded and the land that is forbidden,” explained Jordan. “If [AES] wanted to, they could have turned the Ngäbe from subsistence farmers into wage laborers for a post project phase. But they didn’t care.”

According to its website, AES Changuinola has also provided vocational training courses in masonry and carpentry, to more than 800 impacted community members. But Pedro Abrego claims that fewer than 100 attended the limited sessions, which failed, in any case, to provide sufficient training.

AES declined to comment on questions posed by CorpWatch regarding the effectiveness of its “farm improvement program,” and vocational training sessions.

“[Before] we didn’t lack for anything but [AES] has created a disaster,” said Morales.

Breaking the Ngäbe

Far upstream, beyond the point where the reservoir meets the Changuinola river, Luis Abrego, our Ngäbe guide, moors the boat. On the opposite bank, a group of Ngäbe from a neighboring community are washing clothes, their children bathing in the clear water. There are plans to build more dams in the area, one of which will displace these people, too, explains Abrego. He looks toward the river as it flows downstream, crashing over boulders, rushing past verdant trees until it ceases, finally merging with the silent expanse of the reservoir.

“We want to say that the company has broken everything. It has broken the Ngäbe … psychologically and physically. It has broken us.”

Some of the names in this article have been changed to ensure anonymity

Jennifer is a freelance journalist writing about human rights, hydroelectric development, the extractive industries and corporate malfeasance in Latin America, Africa and the UK.

jenniferjkennedy.com

Guatemala’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Panama: Indigenous communities face imminent eviction: The Barro Blanco HEP dam

by Richard Arghiris* on February 17, 2014 | Intercontinental Cry Magazine | Article reproduced by kind permission.

Clementina Perez (Photo: Oscar Sogandares)

Having fought tirelessly against the unlawful Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam, the indigenous Ngäbe communities on the banks of Panama’s Tabasará river are today threatened with forced eviction at the hands of Panama’s notoriously brutal security forces.

The 29 MW dam, built by a Honduran-owned energy company, Genisa, received funding from three development banks: the Dutch FMO, the German DEG, and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CBIE). The project was approved by the Panamanian government without the free, prior, and informed consent of the affected indigenous communities, who now stand to lose their homes, their livelihoods, and their cultural heritage.

Aside from providing precious sustenance in the form of fish and shrimp staples, and as well as supplying rich silt loam ideal for plantain cultivation, the Tabasará river symbolizes the spiritual lifeblood of the Ngäbe communities on its banks, including the community of Kiadba.

Earlier this year, Kiadba hosted a conference celebrating the 50th anniversary of the ‘discovery’ of the Ngäbe writing system. Bestowed in dreams and visions to the followers of the prophetess Besiko – a young woman who sparked a Ngäbe religious movement called Mama Tata – the written language of Ngäbere is today disseminated in only a handful of schools, including the educational facility in Kiadba.

Attended by hundreds of followers, the conference culminated in a solemn ritual at the site of ancient petroglyphs on the river, whose abstract carvings describe myths and history of the river, including the story of a Tabasará King, who ruled the region prior to the Spanish conquest. Neither the petroglyphs nor Kiadba’s language school are cited in Genisa’s impact assessment – a deeply flawed document according to a UN study in 2012, which concluded that both would be lost forever under reservoir waters if construction of the dam was completed.

Followers of Mama Tata at the petroglyphs (Photo: Oscar Sogandares)

Facing the threat of inundation, the Ngäbe have now established blockades and camps on the river bank to prevent Genisa’s machinery from encroaching on their land. The company recently crossed the water to an 800m wide strip dividing the communities of Kiadba and Quebrada Caña, and commenced felling lumber in the gallery forests. The government has now issued a formal warning demanding that the Ngäbe vacate their lands – today, 17 February 2014, is their deadline.

Sadly, there have been episodic clashes between the police and Panama’s indigenous minorities throughout the four year tenure of President Ricardo Martinelli, who is set to stand down after elections in May. All of those incidents have resulted in injuries to unarmed protesters, and in several shameful instances, permanent injury or death. Despite the disturbing ease with which Panama’s security forces commit acts of violence, the Ngäbe are standing firm. They ask solidarity and vigilance from the international community at this uncertain time.

* Based in Central America, Richard Arghiris is a freelance journalist and guidebook author who writes about responsible travel, human and indigenous rights.

Nicaragua’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

Panama’s national languages

This map will be added once publication permissions have been granted.

The Garífuna of Honduras and Belize

In northern Honduras, where the country’s Caribbean beaches are a major attraction for tourists, development projects clash violently with indigenous land rights issues. Since the early 1980s the Honduran government has made consistent efforts to attract both tourists and foreign investors in the industry, to the point (before the 2009 coup d’état) where the tourism industry was the country’s second largest foreign exchange earner.[1]

The Caribbean coastline of Honduras is home to many Garífuna communities which have ancestral title to their land, and the coastal town of Tela is surrounded by a number of Garífuna villages. The Garífuna have lived in the area for over 200 years, and are descended from the Arawak peoples of the Caribbean islands and escaped African slaves. They have maintained communal land ownership structures, and their land title in the Tela Bay area was established in 1992. Developments in the area, including a luxury tourism development started in 1994, which now lies empty, have brought the Garífuna into conflict with the national government and municipal councils over land rights. In 1997, the national government “conveniently lost” documents relating to Garífuna title to the land.[2]

The communally-held titles grant the Garífuna communities rights to their area in perpetuity, and land may not be sold or transferred to owners outside the community. Not all of the Garífuna land titles, however, are recognised by the Honduran government, which in 1998 reformed the Constitution to permit foreigners to acquire land less than forty km. from the coast, an entitlement previously prohibited. The constitutional change prompted Garífuna fears that big hotel investors would push the Garífuna out of their homes. In 2004 Eva Thorne reported that in some cases these fears had been well-grounded:

the tourism boom of recent years and the consequent demand for valuable beachfront property has created incentives for land invasions and intimidation, as well as bribery and outright violence against Garífuna communities. … Some community members have responded by illegally selling their land to outsiders, often fearing they will lose their land without financial compensation if they refuse to sell.[3]

The Garífuna have also questioned the environmental impacts of the Los Micos project and have rejected an Environmental Impact Assessment that predicted benefits for the area. They claim that the Los Micos site will increase pesticide use and eutrophication of lagoons due to fertilisers used on golf courses, as well as put pressure on the area’s water resources.[4] Fundación Prolansate is an environmental organisation local to the Tela area which has numerous disagreements with OFRANEH, the organisation which represents Garífuna people. But Eduardo Zavala, Fundación Prolansate’s director, also recognises the conflicts caused by the Los Micos project, especially “because it causes people to speculate on land values and prompts an invasion of the areas near to the project.”[5]

The challenges to Garífuna land rights are part of a wider pattern of land rights abuses. International institutions such as the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation seek to shift communal land rights, as practiced by many indigenous peoples in Central America, to systems of individual rights which are easier for international economic players to purchase. Communal land rights have been key to indigenous resistance to developments such as mining and tourism in Central American countries.

The World Bank funds the Programme for the Administration of Lands in Honduras (PATH). Local organisations are afraid that this programme is encouraging individual ownership of land at the expense of traditional communal land ownership practiced by groups such as the Garífuna.[6]

Photo-journalist James Rodríguez explains, “Such a strategy of dividing and buying has already worked in Miami [a Garífuna village near Tela]. The communal land lot was divided in one square block per family, and most of the residents ended up selling out to the DTBT [the Tela Bay Touristic Development Society].”[7] OFRANEH leader Alfredo López bemoans, “The community hardly exists now. It’s a tragedy – they tricked the people into signing over their deeds, and now the community is destroyed.”[8]

The Garífuna of Tela Bay have also suffered direct human rights abuses aimed at forcing them to relinquish their rights to land such as that slated for the development of the Los Micos Beach and Golf Resort. According to a report submitted to the UN Human Rights Committee in October 2006 by US NGO Human Rights First, several major incidents of human rights abuses of the Garífuna have occurred. Some specific abuses are listed in Box 8.3, including death threats, shootings, false imprisonment and house burnings. The evidence associated with some of these points clearly to the Los Micos development and forces associated with it as the origin of these abuses. Activists involved in the land rights campaign at Tela Bay have also alleged corruption by the Honduran government and local authorities. Yani Rosenthal Hidalgo, a recently-appointed minister to the Honduran government, is the son of the owner of PROMOTUR (described as both a development corporation and real estate agency) and a shareholder in the Los Micos project.[9]

[Readers are referred to the interview conducted with OFRANEH leader Alfredo López conducted on 16th August 2010. It is available in the Interviews section of this website.]

[1] This example draws upon Sarah Irving’s work, published in Mowforth, M., Charlton, C. and Munt, I. (2008) Tourism and Responsibility: Perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean, London: Routledge.

[2] Sandra Cuffe (February 2006) ‘Nature Conservation or Territorial Control and Profits?’ www.upsidedownworld.org/main/content/view/194/46

[3] Eva Thorne (September/October 2004) ‘Land Rights and Garífuna Identity’, NACLA Report, 38 (2).

[4] Op.cit. (Cuffe).

[5] Eduardo Zavala (August 2010) in interview, Tela, Honduras.

[6] Human Rights First (November 2005) ‘Garífuna Activists Under Attack in Honduras’.

[7] James Rodríguez (2008) ‘Garífuna Resistance Against Mega-Tourism in Tela Bay’, NACLA, http://nacla.org/node/4884

[8] Alfredo López, quoted in ibid.

[9] Op.cit. (Cuffe).

Undermining Garífuna land rights in Honduras

The Garífuna are descended from the Arawak peoples of the Caribbean islands and escaped Africans who were trafficked into slavery. They are indigenous to Honduras because they arrived on its northern coast before the country gained its independence from Spain in the 1800s, but various individuals, organisations and communities refuse to acknowledge them as being indigenous to Honduras.

The Garífuna have maintained communal land ownership structures in which the patronatos (political representatives of Garífuna communities) hold the communal land titles. “These titles grant the community rights to a given area in perpetuity. They may not sell the land or transfer its ownership outside the community. Improvements, such as houses and other buildings, can be bought and sold within the community, but the land remains inalienable.”[1]

The World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) have legal instruments and policies with provision for group land rights, and the Garífuna have sought to use these to further their land claims within Honduras. At the same time, however, the World Bank has provided Honduras with a loan for coastal and tourism development whose investors require land ownership for their developments. One such example is the granting of $35 million from the IDB for development of the Los Micos tourism development close to the town of Tela.[2]

In 2004, with encouragement from the World Bank, the government of Honduras passed a new Property Law which could bring about the dissolution of community titles and allow third party ownership of land within communally held areas. The law was passed without consultation with any of the indigenous groups of Honduras, thereby contravening the ILO Convention 169 which Honduras had ratified nine years earlier.

The Property Law was later used as the legal framework for the European Union’s Land Programme and the Land Administration Programme of Honduras – PATH by its Spanish initials. The PATH was financed by the World Bank and its aim was essentially that of individualising Garífuna territories so that they could be entered onto the real estate market.[3]

[1] Eva T. Thorne (September/October 2004) ‘Land Rights and Garífuna Identity’, NACLA Report, Vol.38, No.2, North American Congress on Latin America, New York, p.24.

[2] Martin Mowforth, Clive Charlton and Ian Munt (2008) Tourism and Responsibility: Perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean, Routledge, Abingdon, UK.

[3] Thomas Viehweider (7 October 2007) ‘Bahía de Tela: Honduras y el avance del Plan Puebla Panamá’, Centro de Investigaciones Económicas y Políticas de Acción Comunitaria (CIEPAC), Honduras.

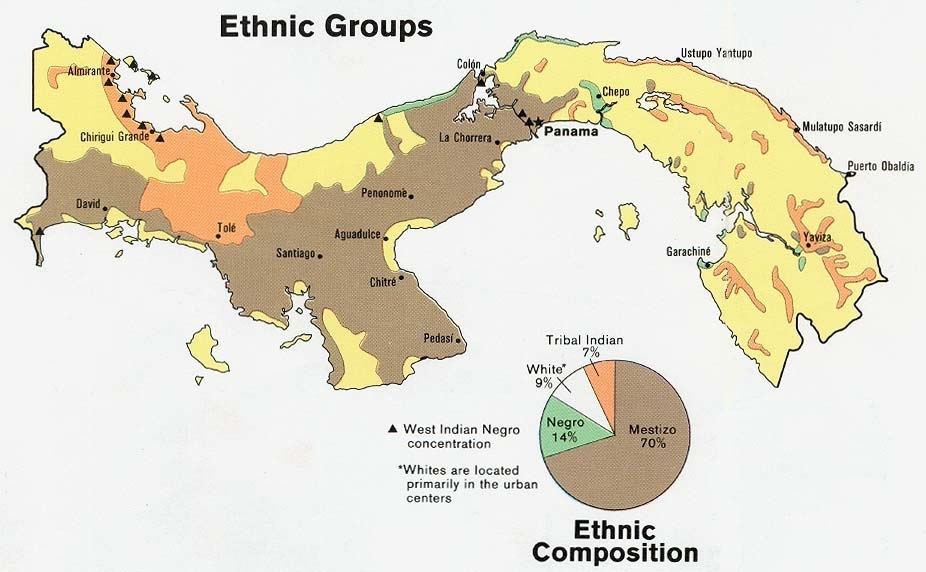

Panama’s ethnic groups

Human rights abuses against the Garífuna

Major incidents of violence perpetrated against the Garífuna have included the following.

The shooting of Gregoria Flores Martínez, the General Co-ordinator of OFRANEH, the main Garífuna community organisation fighting the Los Micos development. Ms. Flores was shot after a series of warnings regarding her campaigns for Garífuna land rights and while collecting testimonies regarding the alleged false imprisonment of another community leader.[1] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a resolution acknowledging the precarious situation for Garífuna activists and asked for protective measures for Ms. Flores and her family, which were not implemented.[2]

The false imprisonment of Alfredo López Alvarez, a leading member of several Garífuna rights organisations, who was arrested in 1997 on drugs charges, found guilty in 2000, exonerated in 2001 and January 2003, but not released until August 2003. In February 2006 the Inter-American Court of Human Rights condemned the Honduran authorities for their detention of López and ordered them to pay reparations, which have not been forthcoming.[3]

The burning of the house of Wilfredo Guerrero, the President of the Committee to Defend the Lands of San Juan, the site of the Los Micos complex. Although no-one was hurt in the fire, documents vital to the Garífuna case were destroyed.[4]

Threats to the life of Jessica García and her children. Ms García, a Garífuna community leader, was approached at home in June 2006 by a man who offered her money to sign a document surrendering Garífuna land rights to the development company PROMOTUR. When she refused, the man put a gun to her head to force her to sign, and threatened her life and those of her children if she publicised the document’s existence.[5] The document, a copy of which was obtained by a US human rights group, is said to hand the disputed territory over to PROMOTUR, guarantee that the Garífuna would abandon legal actions or complaints, and that PROMOTUR would have the right to evict and relocate Garífuna communities. The document is said to have been co-signed by PROMOTUR owner Jaime Rosenthal Oliva.[6]

Jesús Alvarez died following the second of two murder attempts.[7] Jesús was a colleague of Alfredo López and had accused the municipality of Tela of embezzlement in relation to earlier tourist developments.

2006: Community Radio station Faluma Bimetu completely destroyed by fire.[8]

January 2010: the Faluma Bimetu community radio station in the Garífuna village of Triunfo de la Cruz was set alight. Much of the building was destroyed and equipment lost.[9]

7 April 2011: Unidentified arsonists set fire to the home of Teresa Reyes and Radio Faluma Bimetu director Alfredo López at midnight.[10]

[1] Human Rights First (16-17 October 2006) Report to the Human Rights Committee on its consideration of the Initial Report by the Government of Honduras under the International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights, 88th Session.

[2] Human Rights First (6 July 2006) ‘Garífuna Community Leader in Honduras Threatened with Death’, www.humanrightsfirst.org/defenders/hrd_women/alert070606_garifuna.asp

[3] Human Rights First (16-17 October 2006) Report to the Human Rights Committee on its consideration of the Initial Report by the Government of Honduras under the International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights, 88th Session.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Human Rights First (6 July 2006) ‘Garífuna Community Leader in Honduras Threatened with Death’, www.humanrightsfirst.org/defenders/hrd_women/alert070606_garifuna.asp

[7] Rights Action (31 August 2005) ‘The Tourist Industry and Repression in Honduras’, Rights Action, sourced from www.upsidedownworld.org/main/content/view/66/46/

[8] Dick and Mirian Emanelsson (23 January 2011) ‘Radio del Pueblo Garífuna cerrado por terror’, http://vimeo.com/19128569 (accessed 4 February 2011).

[9] OFRANEH (6 January 2010) ‘Urgent! Attack against Garífuna Community Radion in Triunfo de la Cruz’, http://hondurassolidarity.wordpress.com (accessed 6 August 2010).

[10] Reporters Without Borders (13 April 2011) ‘Community radio stations fighting to survive in Honduras’, www.rsf.org/honduras-community-radio-stations-still-13-04-2011,40023.html (accessed 17 April 2011).