In February this year, a Proceso Digital Special Report by Lilian Bonilla warned of increasing hunger in Honduras.

Recent reports estimate that over 225,000 people currently face serious (Phase 4) food insecurity. Phase 4 food insecurity is defined as having gaps in the supply of basic foodstuffs reflecting high levels of under-nutrition and even death. People may eat only once or twice a day with small portions.

Although food insecurity is a global feature, in countries like Honduras the situation is critical due to a range of economic, social and environmental factors. Additionally, the return of a large number of Hondurans deported from the United States will only aggravate this situation.

Interviewed by Proceso Digital, the Coordinator of Food Security and Nutrition Observatory (OBSAN), María Luisa García, stated that currently up to 1.9 million Hondurans suffer a degree of food insecurity at Phase 4 and below, but García warned that this could increase to 2.2 million by the month of June.

Of the 1.9 million Hondurans facing food insecurity, 1.6 million are in Phase 3 (crisis), 174,000 are in Phase 4 (emergency) which forces them to reduce the number of meals they consume each day. (Figures come from the most recent OBSAN report on the Integrated Classification of Food Security in Phases for Honduras in 2024.

The statistics represent an urgent call to politicians, both Honduran and international, and public authorities to take effective measures to prevent the deterioration of food insecurity in Honduras.

A range of factors are responsible for the deterioration. For instance, Storm Sara in 2024 affected the production of basic grains, vegetables, fruit and milk and meat products. Emigration has also been a major problem as the loss of family members reduces the household income and purchasing power. Climate change is also considered an important factor as the most affected region of the country is known as the Dry Corridor – see photo.

A crucial factor, however, is the state of the economy in which levels of unemployment, under-employment and casual employment are very high. A monthly income of 10,000 – 12,000 lempiras (around $400 [USD]) is required to cover what is known as the ‘Basic Basket’ of goods for family feed and survival, but the majority of Hondurans receive less than this in their pay packets.

The food crisis impacts the Dry Corridor of Honduras most strongly

Source: Lilian Bonilla, Proceso Digital, 23 February 2025, ‘El hambre amenaza a 2.2 millones de Hondureños para junio de 2025’, Tegucigalpa, https://proceso.hn

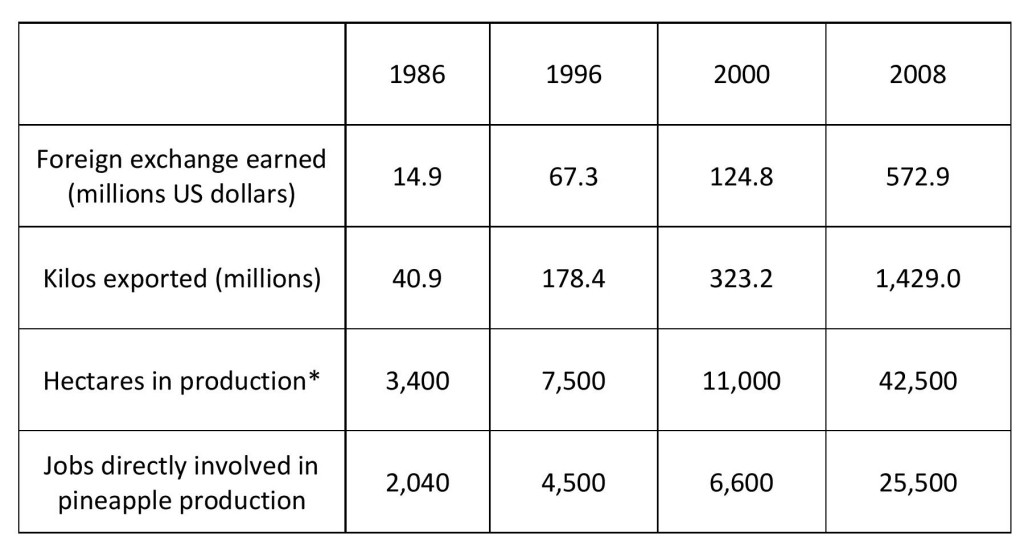

Thank you for supporting our recent urgent action appeal in support of union members at Costa Rican pineapple producer ANEXCO. More than 23,000 emails have been sent to the company, calling on them to end harrassment of union members and to engage in constructive dialogue with the union SINTRAPEM (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores/as del Sector Privado Empresarial). This massive effort, plus several articles in the trade press and an intervention by the UK’s

Thank you for supporting our recent urgent action appeal in support of union members at Costa Rican pineapple producer ANEXCO. More than 23,000 emails have been sent to the company, calling on them to end harrassment of union members and to engage in constructive dialogue with the union SINTRAPEM (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores/as del Sector Privado Empresarial). This massive effort, plus several articles in the trade press and an intervention by the UK’s