Interviewees: Candy and George Gonzalez

Interviewees: Candy and George Gonzalez

Interviewer: Martin Mowforth

Location: San Igancio, Belize

Date: Friday 16th August 2013

Theme: An informal interview about environmental and developmental issues in Belize.

Keywords: TBC

Martin Mowforth (MM): Can you tell us a little bit about your own association with BELPO [Belize Institute of Environmental Law and Policy] and what issues it has dealt with in the past, before you bring us up date with its current issues?

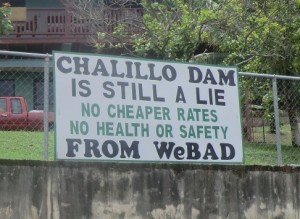

Candy Gonzalez (CG): BELPO stands for the Belize Institute of Environmental Law and Policy. I got involved with BELPO in 1997, and at that time it was just prior to the fight against the Chalillo dam. I was involved in coastal zone management in terms of general environmental issues and environmental impact assessments, and the initial work I did with BELPO was educational in terms of trying to make the environmental laws understandable to people in Belize. When the fight against the Chalillo started, we got involved here in San Ignacio and through BELPO because we saw the problems the Chalillo would cause to this community (the Santa Elena and San Ignacio communities), in terms of what the dam would do to the river and the importance of river tourism to the community, and then the issues of the health and safety of the people living downstream from the dam, (2:28 – unverifiable) meaning that we weren’t aware of and concerned about what it [the Chalillo dam] would do to the rainforest, but there were people were arrowing in on that, but nobody was arrowing in on what it would actually do to the people downstream. We’ve always been very firm in terms of you can’t have a healthy environment without healthy people, and people need a healthy environment to be healthy themselves, and we believe that clean water and a healthy environment are human rights. So that’s been a lot of the focus that we’ve tried bring into the quote, “environmental movement” in Belize, in terms of our perspective.

MM: Okay, thank you very much. Before we get to any current issues, do you want to have a final word about Chalillo and how it progressed to its current situation?

CG: Well, I don’t think there’s a final word today, because we’re still struggling to deal with Chalillo. Chalillo has unfortunately caused all the problems we foresaw; there’s virtually no river tourism, the water quality is poor and they [Belizean Government/BELPO] warn people to not drink the water. People can’t swim in the water because it itches and a lot of people have come out of the river having stomach problems from swallowing the water. We still don’t have a “dam-break” early warning system even though Chalillo went online in 2005, and so we’re facing all these problems and then in 2009 the Vaca dam opened and then there was a third dam put there, but it was really quiet, there was very little said about it. There was a public hearing, and we went to the public hearing – we opposed Vaca because the owners of the Chalillo dam still had not complied with the environmental compliance plan for Chalillo, and we said until they comply with it they shouldn’t be allowed to build another dam, and then make another bunch of promises in terms of mitigation.

We [BELPO] took the Department of Environment to court for failure to make the company comply with the environmental compliance plan, and we took the case in 2007, and we won the case. We got a decision saying that in all the areas that we were contesting, which meant the health and safety issues, that there was no water quality tests that were being shared with the people, that we weren’t getting the tests on the mercury levels in the fish, that we still didn’t have a dam-break early warning system, and that there was no public participation committee, which was supposed to be a two way conversation with the stakeholders, the company and the department of environment. On all those issues, the court ruled that there had been a failure to comply, and we ended up going back to court two different times seeking enforcement, and unfortunately we still don’t have a compliance, but we’re still working on trying to bring attention to the non-compliance and to get the government to force people to comply with the law. So that’s why I say there’s no final word!

MM: Our students will not know about the Chalillo dam, but I shall mention it to some of them if I get a chance, but it would be fine it you could mention precisely what you have just said to me, when you talk to the students. Just as a side, I’ve been visiting quite a lot of – I just want to pause this.

[Apparent pause in the tape at 7:30 and discourse of topics]

MM: I must take a photo of that before I go.

CG: They heard word that they’re going to build a dam on the Mopan River, because the Mopan starts in Belize, goes into Guatemala, and then comes back into Belize. So they were looking for information and support from people because we would be affected by that dam also.

MM: So this in other words is still an active programme, but can you now update us on one or two other programmes that BELPO is currently dealing with.

CG: I sat on the National Environmental Appraisal Committee [NEAC] which is a committee that vets all of the environmental impact assessments for Belize, and I sat on that for over 7 years. One of the things that we did as BELPO was to try and say, okay, we need quality information to make quality decisions. The problem was that the majority of the people on NEAC were in our government employees and so they just, even though they raised points that this is no good, and that is no good, they would still vote in favour of the project because that was their job.

MM: In fear of losing their job as well, presumably.

CG: Right – and the other NGO’s that sat on NEAC at the time, other than me, they had co-management agreements for protected areas.

MM: So, Belize Audubon Society [BAS]?

CG: Right – so they rely on government for the continuation of their co-management agreement, and so a lot of times they voted in favour of [propositions]. So most of the time it was 11-1 vote, or 10-2 once in a while! But what it did in terms of BELPO was that we demonstrated we were across the range of looking at environmental issues that are countrywide, though in the beginning most of our members were here in the Cayo area, either in San Ignacio or Santa Elena – they didn’t stop us, this is not a big country. We were down in Toledo District doing workshops on oil and petroleum in 2002, way before any of the controversy [surrounding] oil and oil exploitation arose, and we also worked with a number of other lawyers from different countries, trying to bring attention to how climate change would affect or impact the [UNESCO] World Heritage sites around the world. We filed a petition with the World Heritage committee, asking for the barrier reef to be put on the endangered list, trying to get a little bit of leverage to try and force the government to do the right thing.

MM: And did the World Heritage people actually put it on the endangered list?

CG: Well, they put it on the endangered list a few years ago, but not related to climate change. They rejected that argument saying that they would have to put in 70% of all the World Heritage sites.

MM: If it was because of that, yeah – okay.

CG: After we brought attention to the problems that we were trying to raise in terms of the government taking parcels [of land] that were within the world heritage site, in terms of development, cruise ship tourism, and how that would impact, was even prior to the whole fight against offshore oil, and we included that in terms of one the reasons why the barrier reef was endangered. It remains, as of earlier this month, through updates from the World Heritage committee that the barrier reef will remain on the endangered list. Along with that, one of our main focuses has been trying to draw attention to the need to protect our rivers and watersheds, so that involves the issue of oil and the issue of dams, because they all impact our watersheds. I do believe, as has been stated by many experts, and I’m no expert, that the future wars will be fought over water, not oil, and we’re rich in water, and we’re ruining our water, and we need to be made aware of and have people appreciate what we have in terms of water resources because people tend to take something for granted until its gone, and we’d rather not get to the point that it’s gone!

MM: Yet another good point for our students, I’d like them to be aware of these struggles over water as well.

CG: The other thing that BELPO continues to do is to try and make the laws understandable to the people on the ground, and we did a guide to public participation in Belize, focusing on the Freedom of Information Act, the Ombudsman Act, and the Environmental Protection Act, giving people sample letters on how they can write a letter. Just last month, we came out with a second edition of it because all of the first edition was gone, and so that was a really happy thing to be able to do, because most of the time you have things that, you always have leftovers of this and leftovers of that, and this time they were all gone!

MM: I’m aware of having lots of leftovers as somebody who writes things, and then having too much left over. That’s great that you did manage to get rid of them all. Just on the World Heritage site, the coastal problem, I’ve been doing a bit of reading over the coastal problems recently, particularly in Belize, and one thing which appears in all of the other central American countries, is the way in which agricultural pesticides are washed down into mangrove areas or affect the reefs, and so on, but not in the case of Belize, it hasn’t been mentioned, that’s the one thing that has studiously not been mentioned.

George Gonzalez (GG): You didn’t mention chemicals.

MM: They don’t. Well, that doesn’t mean to say that they don’t use them though, does it?

GG: Yeah, they use them but they don’t mention them, they try to make it sound like there’s no problem here.

CG: We have tried to bring attention to that as a problem, and there have been a couple of workshops that have been done on land based sources of pollution, as connected to the reef because there’s so much attention that goes into the reef, but everything that happens to our rivers ends up in the reef, so we try and bring attention to what’s being done to the rivers and the banana and the citrus industry do an awful lot. And the sugar canes.

MM: And all the pesticides and all the plastic bags, but the one thing that’s mentioned –

GG: We using something to deal with pesticides – GMO [Genetically Modified Organisms] – a lot of the stuff we grew, and educated the people, is that when they bring GMO, they have to bring the chemicals, it’s one of the chemicals that they are already use here, to make people aware of what happens with all that stuff. Right now, there’s a not major support of GMO, there’s a lot of people against it, but it changes real quick. You get a couple of ministers to say something is good, and the people go for it because they want jobs, or they want to keep their jobs.

CG: Or they want a scholarship for their kids to go to school.

GG: The government has ultimate control over those things.

MM: I gathered that from my recent reading as well, not just from Bruce Babcock’s book, which was an excellent book and very enlightening. One thing that’s mentioned on the coastal thing is the litter – basically bottles, plastic bags, and so on. It struck me that there was one thing being missed, and that was the pesticides, the chemical pesticides and the residues and so on. So I thought I’d ask whether that is still a problem here, even though it’s not mentioned.

CG: It’s definitely a problem.

MM: Really? Okay, fine. On the oil exploration – this is really a last question – can you enlighten me about what the current state is in Belize? Is the government going hell bent for it?

CG: Absolutely. It’s really sad because we’ve done a lot of campaigning, we had a people’s referendum because we have a referendum act in Belize, but the original referendum act was one that says only the government could call for a referendum. So when we had a change of government, they revised it to say that the people could call for a referendum. They really weren’t happy with the changes they made themselves, because when we decided we would do a referendum against offshore oil drilling and drilling in protected areas, thinking about protecting our water and watersheds, the government really opposed the referendum, and ended up where we got the number of signatures that we were supposed to get and more just in case they threw some out, and then government threw 40% of the signatures out because they said the handwriting didn’t look the same, or little things like that. So we went to court on that, challenged it and then on technicality the case was thrown out. The coalition to save our natural heritage which is been the force behind trying to stop the offshore oil drilling and in protected areas, which BELPO is a member of and OCEANA was also a member of the coalition. We did a people’s referendum saying okay, we’ll hold our own referendum just so that you realise how strong the public opinion is, and we got an awful lot of people out to vote – I can’t offhand remember the numbers.

GG: 8/9 thousand or something? [21.53 – check for the figure, but this is what I perceived it as]

CG: It was something like that, of registered voters who came out.

MM: How many now?

GG: I think it’s around 29 or 28 [thousand].

MM: Yeah, that’s a lot in Belize.

CG: The campaign continues; OCEANA and the coalition filed a court case to void concession contracts that the government gave to different oil companies, seven different oil companies, saying that they were illegally granted and there were different parts that did not follow the petroleum act. We won the case and the judge in the case said that the contracts were null and void. The government just recently, because the written decision still has not come out on this, they went saying they wanted a lifting of the injunction on the oil exploration offshore, with these companies where the judge said the contracts were null and void, and they made this argument that the injunction only applied to the government, did not apply to the oil companies, and therefore, the oil companies were going to proceed and government couldn’t do anything, because on their side it was null and void, while any law that I ever came across –

MM: Way of interpretation –

CG: And the Chief Justice ruled in favour of the government on that argument, and I haven’t seen their written decision that is yet to come out.

MM: Are the concessions just for exploration or for exploitation as well?

CG: There’s no line between the two, but our law says that up until 2007, I believe, oil exploration was on the ‘Schedule 1’ list meaning that you had to had an EIA to do exploration, and in 2007 they revised the law saying that exploration didn’t required an EIA, but exploitation did. We already knew from experience that once they find oil, they just start, and it’ll take time for an EIA, and the government doesn’t make them take time for an EIA, they want to get that oil out of the ground as fast and as much they can, so there’s really a very blurred line between the two in terms of concessions for everything – do everything you want. Even with all the promises we’ve seen in so many other countries, where the oil companies have no regard for the people or the land, and I’m always amazed no matter whether or not people think it will be different here, and no matter where you live they always think it will be different.

MM: They also associate oil exploration with great wealth, and if you look at places like Ecuador for instance where poverty levels before oil exploration were at 40% by the UN definitions, and now they’re at 70%, so there’s a higher proportion of the population living in poverty now than there were before. Not only that of course, in the case of Ecuador, they’ve destroyed huge tracks of the Oriente region, which was part of the Amazon basin and left it contaminated, for goodness how many decades in the future, so it certainly leaves them a lot poorer. Despite that, there’s still a general feeling that oil will bring wealth, of course it does to very few people.

GG: You know what they get here? The oil company keeps 95%, the government gets 5%, and of that 5% they have to give 1.5% to the property owner. But they don’t mention that, they mention about the millions that they are going to get, and it’s been made and everything and they make it sound like they’ve made millions, not that the oil company made it, and they’re already almost out of oil, for what 10 years?

CG: Yeah well, Spanish Lookout is.

MM: How long have Spanish Lookout been exploiting oil?

GG: About 10 years, and its running out. They said they don’t have a long time, we only have a few years so what they’re destroying, they’re destroying for a lifetime, only to get a minimal resource.

MM: It’s very similar to gold mining around Central America as well, where the companies leave tiny, tiny proportions 1% or 2% of their revenues, that kind of thing, it’s just frightening. Thank you very much for your thoughts and bringing me up to date with that.

[Onto second recording]

MM: If you’d like to just explain that again, the situation with BEL Fortis and Sinohydro.

CG: Belize Electricity Limited is BEL, and they are the ones that distribute electricity around the country. That used to be owned by Fortis of Canada, and it was nationalised 2 or 3 years ago, and BECO [Belize Electricity Company Limited] is still owned by Fortis, and they own the 3 dams on the Macal River. They sell power to BEL for distribution and BECO, which is the one that owns the dams, are operating under what is called a third master agreement, and the third master agreement them, or guarantees them a 1.5% raise annually. Payment for electricity, whether or not they produce the electricity and compensation for water that goes over the dam in case of flooding, that they don’t produce electricity they can estimate how much electricity was lost by the water going over the dam, and no liability if the dam breaks and there’s loss of life or property downstream. We believe it’s an illegal contract, so if anything happens in term of the dam breaking, we would definitely not believe there’s no liability. Sinohydro are the ones that constructed the dams, they were hired by Fortis, to construct not only the Chalillo but also the Vaca dam, they hired a lot of non-Belizeans but people from Nepal in the main, to come over and work for extremely low pay, and very bad conditions. One of the problems that we’re facing now is more incursions into the rainforest because of all the paths and all the areas that the hydro construction workers opened up, so we’re facing more incursion in terms of taking the natural resources from the Chiquibul Forest and National park, and pretty much clear cutting a lot of the area along the border on the Belize size, they’ve already clear cut the Guatemalan side.

MM: Okay, thank you. And of course the more incursions into the forest, the more it will attract other settlers and colonisers. Do you want to add anything George?

GG: No, I guess the only thing I would say is that in the agreement they are unregulated and when we were fighting Chalillo, we were always amazed of how Fortis would use the excuse of the money its losing on this here, but never mentioned the other one, and we had to remind them it was the same pair of pants. You know, the money went in this pocket and that pocket, for the same person. A lot of people, even though we told them, they just couldn’t grasp that concept, that it is actually happening. Being unregulated, we’re not getting the value of cheap hydro; we’re getting what they say the value is, and one year they tried to charge us, or did charge us, for poles and electrical equipment that was already paid for. So that was an extra, what, 15 million or something?

CG: I think it was 14 million.

GG: It’s not just here; I don’t want people to think that we’re a banana republic and stuff, this going on in the US – upstate New York – Fortis is planning a utility company, a co-op.

CG: In the central Hudson Valley.

GG: And he’s telling them the same stuff that he told us down here, only he’s using down here as his recommendation about what a wonderful guy he is.

CG: And their wonderful environmental history.

GG: And he gave himself an award in the Caribbean.

MM: It’s amazing – it’s incredible how they get away with it. That’s Stan Marshall isn’t it?

GG: They contacted us, and they put us on the radio and TV through satellite, and we let it run on all the stuff that he did, and I think they’re still fighting it. They got permission to buy it.

CG: They bought it and it’s in the appeal process.

GG: But it’s not just here, they’re doing it to there [New York] and then to the people in Canada, they have the same contract that we have here. Some of the ones that found out that it’s just standard big business contracts – it’s call incentives! No taxes, no regulations.

MM: You find that in many other fields of activity as well. Well thank you again, both of you.

END