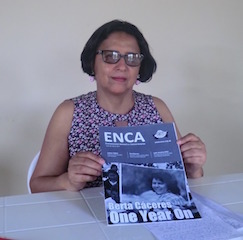

Interviewee: Dina Meza

Interviewer: Martin Mowforth

Location: Tegucigalpa

Date: 22nd May 2017

Key Words: human rights; rights defenders; environmental defenders; journalism; media censorship; precautionary measures; freedom of expression

.

.

Martin Mowforth (MM): OK, interview with Dina Meza, in Tegucigualpa, Monday 22 May, regarding the threats to defenders of human rights, environmental rights, land rights and social rights in Honduras. Dina, if it’s OK with you, I’d like to move from the personal situation which affects you to the national and international situation in Honduras. So my first question is: can you describe your own current situation of security and insecurity in Honduras? In terms of your work and your daily life.

Dina Meza (DM): Well, I’ve been involved since 1989 in the activities associated with the defence of human rights through the exercise of journalism. And I think that we can consider the situation from after I returned from England in 2013 – as I returned, what happened and what has happened after that time.

Well, I arrived back in the country and in the first few months there was no problem. But then the threats began again, there was an attempted kidnapping. I had to move house again, and there were threats to my children and the situation was worsening.

From that time in 2013 to the present I’ve moved house three times, the vehicles of our families have been vandalised, we have to have armed guards at the entrance to the house. Then the President ordered an investigation into my personal case and the case of other human rights defenders. And yet he [the President] put in place a list of those whose private life would be investigated and who would be tracked. That was information that came to me from a source in the Casa Presidencial. And then we published it because I considered that it was very dangerous to be on that black list, and logically the tracking began almost immediately after I was told that this information existed. Then we had constant …. well, our vehicle tyres were damaged; at various times I couldn’t communicate by telephone. It left me completely isolated and also there was, and there still is, a lot of intervention on the phone.

I’m currently accompanied by Peace Brigades International. After going to England, they have accompanied me since May 2014. Compared with how it was before going to England, the threats now are more subtle. But they are always there. In a country with such impunity we have this type of thing on normal days, and more so when you’re involved in ultra-dangerous activities such as journalism and the defence of human rights.

The threats have kept coming constantly. Peace Brigades International has done an analysis and has produced communications on these threats. Also we’ve had to refer to the international authorities. Last year I went to Madrid and Barcelona. We were in a forum regarding the issue of women rights defenders and the things they were confronted with.

Already this year, less than a month ago, I was threatened in a bus. I was travelling in a bus because of a shortage of cash, and a man sat beside me and said to me that he was heavily armed and that at the back of the bus were more armed men who had been ordered to kill me, but that I should remain calm. So I said, “why do they want to kill me? What’s the problem?” Then he said. “No, the order is there, we can’t ignore it.” The man made as if he had received a telephone call, saying that he was wrong, that he had been wrong, and that I didn’t have blue eyes. But he never saw my eyes. Then he was threatening me the whole route, and I was becoming convinced, because after his supposed call, which was a lie, he told me he had to take a photograph. I said to him: “You can’t take a photo of me because it doesn’t make sense for you to take a photo of me.” We were talking like this over the whole route. In reality, God gave me a lot of strength to remain calm, and finally I said to him, “Look, I have to get off here,” and I got off at a stop. Then I shook his hand and wished him many blessings and that God would bless him on that day, and I got off the bus. The problem is that when I got off, I said to myself that it was all over. But I went and took refuge in a pharmacy, and when I left it, I saw four men standing on a corner. Then I said to myself that yes, this was certainly [a threat]. [Nervous laugh.] Then a vehicle was stationed opposite the pharmacy with flashing lights and darkened windows – like the police vehicles. And so I called Peace Brigades International for them to come and rescue me from the pharmacy and that they should get there by taxi so that I can get out of the situation I was in.

So that was less than a month ago. That situation put me outside the protection mechanism that we have in the country. So three weeks have passed since I resorted to the mechanism. They offered me a panic button, they offered me an escort, police and military; they offered me all the military possibilities, except investigation. And also a risk assessment to find the origins of the threats. So far, after three weeks, I haven’t had any contact with the protection mechanism. The panic button, for use just in emergencies, they haven’t given me; they haven’t done a risk assessment. And here we are hoping that the State of Honduras will take action.

The same thing happened with the previous threats. I was making denunciations to the Public Ministry, and they never made any investigation, and they lost my case notes. They disappeared mysteriously and they’ve never done anything.

So that implies that the threats are not de-activated, but simply the same things will continue and get worse.

MM: Yes.

DM: That’s what happened in the case of Berta Cáceres who had made 33 denunciations. And the State never did anything. Afterwards they washed their hands of the matter, saying that she had moved and had not notified them of where she had moved to.

But that is the State that we have, a State in total impunity, and which does nothing and that offers no protection to human rights defenders.

So the situation that we have is one in which we have threats against me, or there’s tracking of my older children, or we’re being watched, or there’s telephone tapping, mainly of my elder daughter.

MM:Yes.

DM:I think that this is already a major technique, to make differentiated attacks on the human rights defenders, to attack not just us, but also our sons and daughters, so that we get into a period of destabilisation, so that we abandon our work.

I’ve had to change my security completely and to take other measures. I don’t go on the bus any longer, I’ve had to look for Support to cover at least a few months of transport by taxis and other means of transport.

MM:Yes

DM:So, such is the situation. They want to intimidate us whilst they intensify the human rights violations. This electoral year, like the previous electoral year when I spoke to you in 2013. The situation is going to be super-complicated as we are already seeing. After yesterday there is now an opposition alliance to the Juan Orlando Hernández regime.

MM:Yes.

DM:So as of now, the war is on. There’s going to be masses of attacks, not just by the media, but also physically and all kinds of things against people who are within the political opposition, journalists who aren’t following the President’s agenda, and who aren’t with his re-election. And things of that style.

So we’re in a crisis situation greater than we had in 2013, because this man wants to stay in power, he’s happy with it, and we’ve no idea how many years he wants to stay ensconced in the Casa Presidencial. So that’s the current situation.

MM:OK. As far as the black list goes, who are the creators of the list? Is it governmental?

DM:Yes, it’s governmental. According to what my source told me, it cameo ut of what they call the Crisis Room which means that it came from the President to the Crisis Room as work that remains to be done. And it’s been like that since the 1980s – right? On the back of the coup d’état, various lists emerged – there were lists of defenders, I was on a list as a journalist, I think there were students of journalism and other students at the university who were involved in social protest who had been criminalised. So, we were around ten people – no, I was accredited, given that I wasn’t able to reveal the source. So what they were doing was indirectly sending me threatening messages telling me that if I didn’t tell them the source they could make a charge against me or something like that.

So I told then, “Charge me – that’s no problem. Because we have what’s called ‘protection of the source’.” So I couldn’t say who gave me the list or anything about the source, and nor could anyone oblige me or prosecute me for that.

MM:OK. This is a bit of a diversion from the topic, but what do you think of the chances of the Alliance in November? [This refers to the newly formed Alliance of opposition parties in Honduras, and to the forthcoming elections in November.]

Both laughing.

DM:It’s pretty complicated because there’s a culture of rubbishing any alliances which form, whether they are good or bad. But it’s good that there’s an alliance against the current President. If there were transparent elections, I think that the Alliance would win.

MM:Yes?

DM:But he’s not going to have transparent elections, and what’s more the electoral system is the same – there haven’t been any modifications. Obviously it’s in the hands of the current President to change the results. As it was in 2013.

MM:Yes.

DM:So I don’t see a lot of hope from this point of view. But I think that the people with these ideas could produce a worthwhile alliance of this type.

I’m told that in the communities people are cool about the public arrival of the Alliance. And we fully understand that as it gets going there is going to be a lot of repression because they’ll use the political activism of the National Party. There are ultra-violent sectors amongst them who threaten and kill people – ultra-violent. Apart from that we have para-militarism in the country that can be used and we can say that perhaps those involved in narco-trafficking and organised crime and similar activities can also be deployed. These were the false positives used in Colombia that have also been established here in Honduras. So, I think it [the Alliance] is a good exercise for the electorate, or so it seems to me. But I don’t see much hope in terms of change.

MM:OK. Las computadoras para las elecciones ¿son por el control del Gobierno?

DM:Si. El Tribunal Supremo Electoral

MM:¿Un organismo independiente?

DM:Well, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal was supposedly restructured – previously it was known as the National Tribunal of Elections, and then it became the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. The objective [of this change] was that it would be an independent organisation; and that the magistrates who were nominated to it would not belong to any political party, only that they would be honourable people and that they would be honest. The problem is that all those who are there actually respond to political parties, or simply that they’ve changed the name of their party affiliation which no longer functions. So it’s very normal that when you’re counting votes and the other people are winning, it’s not him who’s in control – the light goes and various situations occur. It happened to me in 2000, in 1998 Presidential elections and I was covering them. They were moving all the team before the end of the count. It was drawn to my attention and I began to document it. I was working in a media corporation, and I got all the information with photos and everything, and when I wrote my piece the editors called me in – the boss and his chief editor. They sat me down and told me, “your piece isn’t going to go through.”

“Why not?” I said to them.

“Because what you’ve written is false.”

So I said to them, “I’ve got photos which support me, and here I can show you.”

But they said to me, “Look, your note is not going to go through because the Director has said that it’s not going through.”

So, they have these ways of controlling what happens. Until there’s a restructuring, a radical change of the political electoral system in the country, there aren’t going to be transparent elections.

MM:Yes. A structural change?

DM:Yes, clearly.

MM:OK.¿And can the situation be helped by international observation?

DM:Yes, assistance, it seems to me that it’s vital. I posed this in 2015, in London, when we met with Peace Brigades International (PBI) and a group of other organisations to set up an urgent and multi-disciplinary human rights observation mission, right? To defend us we need lawyers, defenders, journalists to come to the country. It seems to me that it’s vital, and in this electoral context it’s super-important. Well, in 2013 it helped a lot, despite the fact that yes there was fraud, but it neutralised situations of threats and risks against defenders, largely those outside of Tegucigalpa and who had no support, like the more direct support that we had in the cities. I think it’s vital that we take up that issue again.

MM:OK. Y tú tienes medidas de precaución de la Comisión Inter-Americana de Derechos Humanos? ¿O no?

DM:Well, I must confess to you that publicly I always say that I have these measures. But currently they’re not operational and the Inter-American Commission doesn’t activate them. So, for the moment I don’t have them. But publicly I always say I have them in order to neutralise whatever situation may arise.

MM:OK. But in reality they don’t serve the purpose of precaution.

DM:The truth of the matter is that yes, sure, the Inter-American Commission has granted the measures, but the state of Honduras doesn’t implement them and doesn’t comply.

Back in 2007, I had a police escort because I was in another organisation where they killed a lawyer who was on my team. So I used to go around with two armed police agents, and it was an unpleasant situation. It stigmatised me personally, in my barrio the neighbours would see me as a delinquent because the police arrived and began shouting my name and everything with a megaphone. So it stigmatised me in the neighbourhood. And yet they never investigated the threats. So, although it’s right that the precautionary measures are worth it, but I think there must be some follow-up. As regards what the Inter-American Court is doing with its sentencing, I think the Inter-American Commission must make the time to check those countries which are not complying with the measures.

MM:And can you say something about the situation of freedom of expression and freedom of information in Honduras? And perhaps the situation of the owners of the communications media? Specifically I’m thinking and wondering about the possibility of publishing all your articles – are they edited, cancelled or prohibited?

DM:There are different situations as far as freedom of expression and information goes.

As regards freedom of expression there are various levels. One: is the crimes against journalists and communication workers. Around 66 have been murdered since the coup. There have been only four sentences of supposed material authors. But there have been no investigations that link journalistic work the crimes that occur against them; neither has there been any prosecution of the intellectual authors.

Secondly, also there are direct threats and indirect threats sending messages by telephone, saying you’d better keep quiet, shut your mouth, that what happened to such and such a journalist will happen to you, and they mention a particular assassinated journalist.

Also, there are incursions into the communications media, with unknown men, armed, turning up and issuing threats.

Also, programmes are censored, and there are programme closures – by order of the government. They call the media and threaten them that they’ll close down the media, or they’ll close down a particular programme. There have been various programme close-downs.

Another is that there are threats to publish information. There are lawsuits for defamation and slander. Two journalists are already under sentence for this. One, Julio Ernesto Alvarado, has one year and four months of prison and the suspension of the right to exercise journalism for the same period. And we’re supporting him as an organisation, because after I came back from England, a group of people and I created the Association for Democracy and Human Rights. You’ll find it at pasosdeanimagrande.com which is a journal that we’re running and also we’re providing legal accompaniment for people with scarce resources who are the object of libel and defamation lawsuits.

So with PEN International we managed to raise the case of Julio Ernesto Alvarado with the Inter-American Human Rights Commission and we are pursuing the case. We managed to get the sentence suspended and the Inter-American Commission would study the admissibility of the case or not, and it’s still at that point.

So we’ll see what the Inter-American Commission says – we’ve been presenting the case since 2015 and we still haven’t had a reply – it’s a really delayed process.

But last year in August, another journalist, Ariel Davicente, covering the south of the country, was convicted. He denounced some irregularities of a police chief who was committing abuses of authority, and that he was involved in illegal activities. The police chief contested it, and so he was sentenced by a court to three years in prison, with suspension of the practice of journalism for the same three years, and having to pay all the costs of the judgement. Moreover, the police chief is going to open a civil case so that he can get, supposedly, compensation for the moral damages which he has been caused. Currently the case is under study by the Supreme Court of Justice which has to make a pronouncement through the Sentencing Court. So if the Court confirms this resolution, our colleague is going to go to prison, will be suspended from journalism and will have to pay all that money. So that’s a bit of Julio Ernesto Alvarado’s case – we’re supporting him and also presenting his case to the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights.

MM:But did you say that the journalist is out of the country?

DM:No. This journalist is in the south of the country.

MM:OK.

DM:He’s continuing to practice his journalism. He’s one of the critical journalists of the southern zone. And both of the two who are critics have defamation and libel cases against them. Their cases represent one form of closure.

The other form of closing down is with the information sources. They don’t let anybody – I, for instance, can’t get to the Casa Presidencial, nor to the National Congress, because all they have to do is read my name and there’s no way I can be there. So they require your accreditations, they ask for loads of things, and that’s just to verify your identity. But they close down the sources too.

And another thing is that the carrot-and-stick are used with government publicity. At the moment all the funds destined for publicity are focussed on the Casa Presidencial. Initially that was being managed by the President’s brother, but now it’s managed by another person. But for sure the focus of publicity is associated with control of the journalists. We can say that a journalist who doesn’t stick to the government’s agenda, simply isn’t given a contract or a permit.

So, those are the ways of controlling the press.

And on the other hand …..

MM:[Inaudible)

DM:Yes, and also laws have been made to limit the access to information. We have a very good law, the law of access to public information. But it’s blocked by the official secrets law. They created this law to encrypt information for 25 years – 5, 10, 15, 25 years, at the discretion of the government officials. Or maybe somebody can tell you that this information could affect national security and therefore cannot be made public. So this law also restricts our work, as well as that of the rest of society too.

So those are the ways in which our work is restricted. Moreover, there are many campaigns to stigmatize us. The President tells journalists that we are not on his agenda, that we are inflammatory, that we get in the way of development and that we foment campaigns against the government each time we go to events like the periodic universal examination of the United Nations Human Rights Council – when we go to speak on what is happening, and also when we go to the Inter-American Commission. And all these campaigns of stigmatisation, what they aim to do is generate hatred against us.

And they’ve also created some reforms which limit the freedom of expression. Among these are reforms to the Penal Code. In article 3.35 where it talks of what can be taken as an apology for terrorism, and apology for hatred, and that journalists are responsible for that and that we can be taken to court for it.

Likewise, those who make use of social protest are also criminalised. And they included another clause for the financiers. In other words, what they want is to let no one support the civil society that is doing Human Rights defense with funds so that we can carry out the work. That way generates terror in the financiers so that they no longer finance us – in Nicaraguan style with, with Daniel Ortega who some years ago [closed?] an organisation taking its documents – well, it was a disaster. And that’s exactly what is being applied here.

And well, they also talk of the crime of usurpation [illegal expropriation] which now carries a greater penalty than previously, similar to defamation and libel the penalties for which have also risen.

And with that the students of the National University make use of the right to protest; and the crime of usurpation didn’t hit them last year in 2015 – it didn’t work. So now they’ve added a little clause to the article that says: ‘take public buildings other than your house’. They put in that little bit, because we said: there can be no usurpation if they study in the university. In other words, they do not have the purpose of appropriating the university, but simply making use of freedom of expression through social protest.

So those are some of the things that are happening.

MM:Is there any evidence that social media is managing to get round these obstacles?

DM:Yes, of course because the communications media are controlled by the government.

They have their accords, they have an agreement so that the publishers who have debts for electricity or water can swap them for the right to publish.

So they have a law for that too.

MM:Yes, but I’m thinking of the possibility that the protests, those protesting, can use social media to get round these obstacles put there by the government.

DM:Yes, clearly. There are already cases of people who have used Facebook who have been had proceedings started against them. There’s a young person who posted a Facebook message repeating information from one of the media that said that a bank was going to close because of money laundering. Well he was caught, the police turned up and arrested him for having written that on Facebook.

Another journalist in the central zone of the country commented on his Facebook page that a bridge was very expensive and that it was the most expensive bridge he had ever seen. The mayoress took him to court but we managed to nullify the lawsuit because the mayoress was using public money to defend herself as her lawyer in this case was the municipality lawyer when it was in fact a private case.

So they’re making small or great steps as regards criminalizing the use of social networks. And they’re calling them cyber crimes. Here the social networks aren’t very active.

MM:Yes.

DM:It may be immediately that there is some repression, an attack, or whatever may be against a human right, there it is. So, although for sure the corporate media are closing down your spaces, even so, through the social networks, everybody knows about it.

MM:OK.

DM:What you were asking about the concentration of media ownership, this continues. The State of Honduras committed itself to democratise the radio communications spectrum, but it hasn’t done it.

In 2012, or 2013, it distributed the frequencies, but the majority of these frequencies they gave to political activists of the two traditional parties, to activists of the current party in government. And they closed the spaces of social organisations to which they denied frequencies citing a load of obstacles which they created. So they didn’t allocate frequencies and the few that they did give out were to some indigenous groups and some communities that were under real stress. They presented administrative hurdles, red tape associated with the National Telecommunications Commission, they implemented power cuts, they ruined the equipment, there were calls to CONATEL to explain why, for example, it was blocking other frequencies and doing things like that.

So there are indirect means of censorship which they are using, apart from the other more direct threats.

MM:Yes. One final question please. Do you have any suggestions for people, activists, of the supposedly first world – in England? For example, how can we help you more than in the past; in the future, can we help in any better ways? Are there various measures that we can take, various things that we can do?

DM:Good, in the European Union we met with a delegate from Europe and asked him why they continue giving money that is used for repression. He said, “no, no, no, we won’t deal with that because it’s already decided that the money will be given to the government – and ta ta ta.”

I think that if you close down that valve, the valve that is the money requested for the protection of human rights, if you close that opening because of non-compliance, then that is a big step.

MM:Yes.

DM:Because it must be monitored, it must have field investigation to see what’s happening – and not just to receive government reports, but they must also talk with the victims, they must verify the indicators to ensure their certainty.

On the other hand, I think that it’s important that the directives of the European Union put these into effect. In Honduras we have had an Ambassador who has made good use of the directives. In my case, which I’ve raised, it’s worked well – although others have complained.

But I think that complying with the EU directives must be more profound – at the level of those countries which give funds for education, for human rights – that must be controlled. Because the opposite is its use for the purchase of more instruments of repression, like rockets, like vehicles for firing tear gas, more personnel for surveillance. And all these elements intensify the militarism which is what we experience in this situation.

On the other hand, I think it’s really important start proceedings against or to make investigations into the actions of the Public Ministry. In the case of Berta Cáceres, they’re not letting anyone see the case notes, they aren’t giving access to these notes to the family nor to the lawyers, and so we don’t know how the situation is going. As for journalists, I’ve asked for information and what they say is that the Public Ministry law doesn’t allow the imparting of that information. When we ask we’re just given general information which isn’t going to affect any case.

So they hide under this cloak, to keep cases locked away, doing nothing about them. Why? At times they say they don’t have the fuel, or they don’t have a vehicle, so they can’t move. But there are cases which don’t need that, all they need is the political will to take action, that’s all.

I think that the Judicial Power is functioning in the same way as the Supreme Court of Justice, in that it acts at the speed of light to criminalise defenders, but shelves the cases which are presented by defenders for the investigation of the perpetrators.

So I think that the powers of the state – the Legislature, which approves damaging laws – no? – gives concessions for natural resources such as the rivers – that brings more violence. It pays no respect to the informed consultations with the populations. It makes concessions for mining, open-cast mining, which is responsible for a great deal of environmental contamination and has repercussions in the communities, even displacing them.

So, all that is what we have to face in this situation.

MM:Dina, very many thanks for your words, for your time. I’m sure that you have a lot to do after your journey to El Salvador, so I’m very grateful to you for your time. Very many thanks.

DM:Yes, thanks to you too. ENCA has been a good accomplice to me in this project. We’ve set up an office and we’ve started an online newspaper – pasosdeanimalesgrande.com – and we accompany people who have no or few resources; thanks to the support that you have provided to us.

Interviewee: Berta Oliva De Nativi, Founder of COFADEH, the Committee of Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras

Interviewee: Berta Oliva De Nativi, Founder of COFADEH, the Committee of Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras

Interviewee: Dr Juan Almendares

Interviewee: Dr Juan Almendares

Interviewee: Gerson Suazo

Interviewee: Gerson Suazo Interviewees: (from left in photo) Elvín Maldonado, María-José Bonilla, and Juan Granados – All members of the Camamento Environmentalist Movement (CAM)

Interviewees: (from left in photo) Elvín Maldonado, María-José Bonilla, and Juan Granados – All members of the Camamento Environmentalist Movement (CAM)

Interviewees: COPINH (Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organisations of Honduras)

Interviewees: COPINH (Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organisations of Honduras) Interviewee: Alfredo López

Interviewee: Alfredo López Interviewee: Bertha Oliva, President of COFADEH (the Committee of Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras)

Interviewee: Bertha Oliva, President of COFADEH (the Committee of Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras)