By James Phillips, Covert Action Magazine, May 3, 2023

This article is rather longer than those usually included in the bi-monthly additions to The Violence of Development website, but we deem it to be not just an informative and valuable guide to the current situation of governance in Honduras, but also a helpful summary of the history behind this situation. We are grateful to James Phillips and to Covert Action Magazine for their permission to reproduce the article in our website.

James Phillips is a cultural and political anthropologist with 40 years as a student of Central America. He has authored numerous articles and book chapters, and his latest book (‘Extracting Honduras: Resource Exploitation, Displacement and Forced Migration’) was published by Lexington Books in 2022. He can be reached at: phillipsj@sou.edu

The original article in Covert Action Magazine can be found at: https://covertactionmagazine.com/2023/05/03/while-projecting-a-friendly-face-and-an-extended-hand-the-biden-administration-has-continually-challenged-the-initiatives-of-honduras-new-progressive-government-and-ignored-the-voice-of-the/

Key words: Xiomara Castro; Juan Orlando Hernández; coup d’état; Zones of Special Economic Development (ZEDEs); US intervention; corruption; violence; assassinations

Honduras President Xiomara Castro [Source: resistediverso.blogspot.com]

In November 2021, Hondurans resoundingly elected a new government, headed by President Xiomara Castro, that pledged to end official corruption, reduce violence, and move away from reliance upon a destructive, extractive economy controlled by foreign corporations.

Castro’s government committed to moving the country toward an economy that allowed people to work for themselves, their families, and their communities instead of toiling for others while falling ever deeper into poverty and dependency. That election seemed a remarkable break, especially from the previous 12 years. But various dilemmas have plagued the new government’s attempts at change.

Xiomara Castro at her inauguration. [Source: Photo courtesy of Lucy Edwards]

The former Honduran government of Juan Orlando Hernández, unwaveringly supported by the U.S., became a nationwide criminal enterprise that included gangs, drug traffickers and corrupt corporate interests—elements that continue today to foment daily violence and resistance within Honduras against any movement by the new government toward reform and renovation.

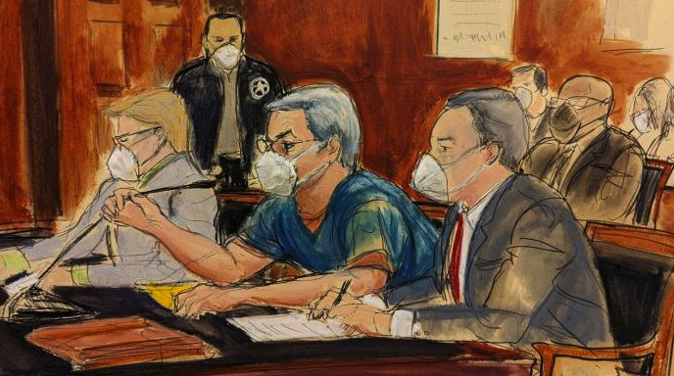

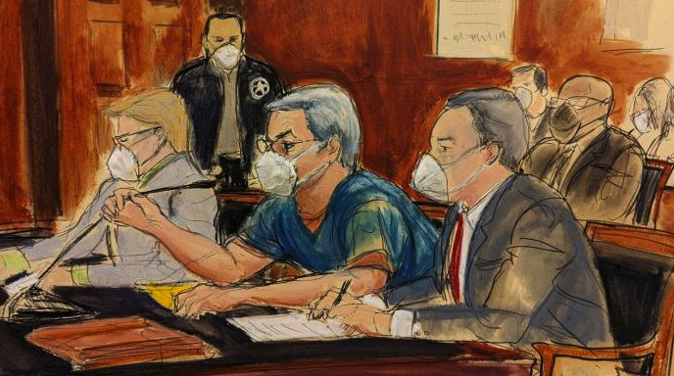

Sketch shows former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández in court after being charged with narco-corruption. [Source: cnn.com]

And the Biden administration has continually challenged the initiatives of the new Castro government and ignored the voice of the Honduran people.

The U.S. maintains control under the guise of partnership and assistance, peppered with criticisms and veiled threats. Given these pressures, what are the prospects for the future of Honduras, and for U.S. policy and practice?

Elections and the Popular Will

To understand the importance of the election of Xiomara Castro, it is useful to compare it to the three previous Honduran elections. The 2009 election was held in the wake of a coup d’état and it was “won” by those who had perpetrated the coup. The voting took place as the military and the police violently repressed massive popular protests that continued for months after the coup.

In the presidential elections of 2013 and 2017, Juan Orlando Hernández—one of the chief proponents of the 2009 coup—claimed victory, despite widespread claims that his National Party (Partido Nacional, PN) had won through fraud.

Hernández was not legally eligible to run for re-election in 2017 (the Honduran Constitution prohibits a president from running for a second term), but the Supreme Court that he had stacked with his own judges allowed it, ignoring the Constitution.

After each of these elections, protests erupted and were brutally repressed by security forces with liberal use of tear gas, beatings, arrests and killings. These post-coup years of National Party rule, when Hernández retained the presidency and systematically concentrated the powers of the state under his control, were marked by extreme violence (with a murder rate and a femicide rate among the highest in the world), pervasive official corruption, criminality with impunity, and deepening poverty, both for the nation and for a majority of Hondurans.

Meanwhile, the U.S. State Department accepted the validity of these elections and continued to certify that the Honduran government was making progress in protecting human rights and democracy—a conclusion that could only be arrived at by systematically ignoring the loud protesting voices of Honduran human rights leaders and popular organisations.

Demonstrators carry a banner reading, “When tyranny is law, revolution is order. Damn the soldier who points his weapon at his people.” Tegucigalpa, Honduras, December 3, 2017. [Source: upsidedownworld.org]

As the 2021 elections approached, Hernández’s hand-picked successor and the National Party hoped to retain power by offering “bonuses” to groups of people, especially poor households in rural areas, who would promise to vote for the PN. The PN also kept trying to revise voting laws and procedures so as to control local election committees, and to exercise coercion where it might be effective.

To oppose Hernández and the PN, three opposition political parties joined to support Xiomara Castro for president, with a platform that pledged to eliminate official corruption and impunity, protect women and human rights, and transform the country’s heavy dependence on resource extraction and foreign investment that had reduced many Hondurans to poverty.

In November 2021, the Honduran people overwhelmingly elected Castro. The parties supporting her gained a fragile majority in the Congress and control of several major cities. In the year since Castro’s inauguration, her government has faced increasing resistance from Hondurans who fear major reform; increasing criticism and impatience from those who voted for her and now want to see real change; and constant pressure from the United States to abandon plans for meaningful change. For the new Honduran government, this is a time of hope and danger.

Achievements of the New Government

Despite the headwinds, the Castro government has managed in its first year to take important steps toward fulfilling the promise of a better future for the country. The new Congress has repealed some of the previous legislation that had enabled impunity, corruption and the curtailment of labour rights.

The government is engaged in negotiations with the United Nations to establish an independent body that can investigate and begin to prosecute corruption. The government has also intervened in at least a few prominent cases to seek satisfactory solutions where communities were being forcibly evicted by corporations or large landowners. It has helped to dismiss some cases brought against human rights and environmental defenders by supporters of the previous government.

The President and the Congress have established entities and endorsed educational efforts to address the high rates of femicide in the country, although the results so far have been meager. The Congress passed a law establishing important assistance for the 300,000 Hondurans internally displaced by unlawful eviction and gang violence. These (and more) are a few important steps that hold promise.

The Castro government also declared a 30-day “state of exception” that suspended some basic rights in various neighbourhoods in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula in order to crack down on the widespread criminal extortion of poor communities, small and medium-sized businesses, and the transport sector. The Congress then extended this for several more weeks.

Many Hondurans applauded this, since extortion has affected so much of Honduran daily life. But the use of the police and the military to carry out the crackdown is controversial, given the allegedly deep involvement of the security forces in criminal enterprises and their many alleged and documented human rights abuses.

[Source: Confidencialhn.com]

The Dilemma of a Honduras “Open for Business”

At the core of the Castro programme is a transition from the foreign-dominated extractive political economy of the country—one that had in the past 12 years reduced Hondurans and their communities to dependents working to enrich others—to an economy that favoured the promotion of local initiative and greater national self-reliance.

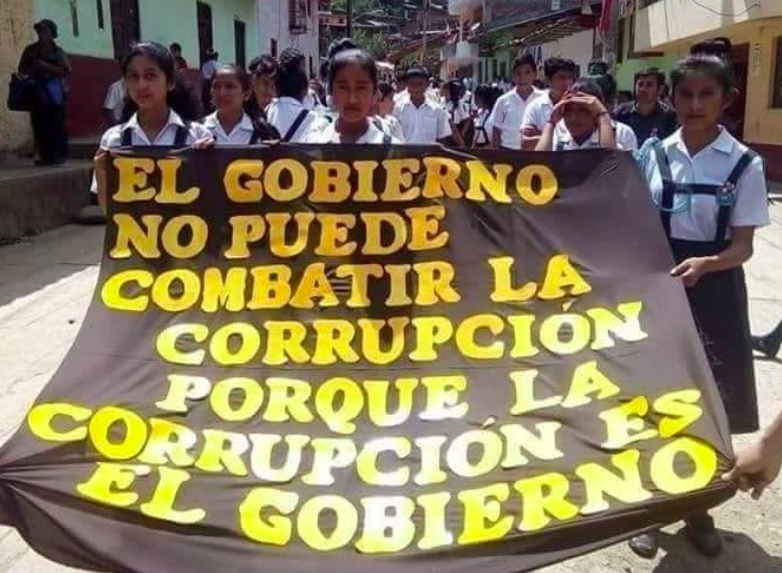

The implications of such a transition are not only economic. They also signal a shift in identity and dignity for individuals, communities, and the nation itself. Clearly, such a transition would threaten the current situation in which Honduras is a colony, a source from which foreign corporate interests and a few wealthy Hondurans extract resources while leaving the Honduran people with a poverty level that currently stands at upwards of 73%, the second highest in the hemisphere. Corruption and state-sponsored or condoned violence are bitter fruits of this externally oriented colonial model. All of this is what the Xiomara Castro government has pledged to change, and what the Honduran people overwhelmingly voted to change.

Poverty remains ubiquitous in Honduras. [Source: globalgiving.org]

is brewing in Honduras between the Castro government and the promoters and investors of the “special development and employment zones” (

zonas especiales de desarrollo y empleo, ZEDEs). The ZEDEs are essentially sovereign enclaves for foreign investment and enterprise that are carved out of Honduran territory.

There are currently several ZEDEs in Honduras, all in the early or initial stages of development. For many Hondurans, including members of the business elite, the ZEDES represent a threat to Honduran communities and businesses and a violation of national sovereignty. Castro’s government and the new Honduran Congress recently repealed the law of the previous government that had authorized the creation of ZEDES.

Blueprint for special economic zone. [Source: proceso.hn]

Developers of the Prospera ZEDE have charged breach of contract and have

threatened a $10.75 billion lawsuit against the Honduran government unless the Congress reinstates legal permission for the ZEDEs. Additional pressure came from a letter by two U.S. Senators (a Democrat and a Republican) supporting the ZEDEs and criticizing the Castro government for obstructing free enterprise and “development” initiatives.

A Florida Congressman warned Honduras that it faces “serious sanctions” if it “illegally expropriates” U.S. investments in the Prospera ZEDE. U.S. Ambassador to Honduras Laura Dogu urged the government to keep the country open for business, by which she clearly meant business as usual, including the ZEDEs.

Laura Dogu [Source: processo.hn] Her remarks were taken as intrusive criticism, even a mildly veiled threat, and provoked a pointed response from Foreign Minister Eduardo Enrique Reina.

There are legal arguments to counter these threats, but the threats are significant, and they have generated further threats of

legal action against the new government. Meanwhile, many Hondurans are

demanding the repeal of the ZEDEs. The government feels pressure from outside and from its own people pulling in opposite directions.

From his prison cell in New York, Hernández himself issued an open letter to the people of Honduras. He and members of his close circle are in detention in the United States on charges of overseeing massive drug trafficking from Honduras to the U.S. during his presidency.

His open letter was a litany of his accomplishments for the Honduran people. The actual benefit of most of these “accomplishments” is questionable, but the letter painted a rosy picture of his presidency, ignoring the rise in violence, corruption and poverty under his rule. He also criticized the new government.

Why was Hernández allowed to write and publish this letter while he is in custody in the U.S.? It could only happen with the permission, perhaps even the blessing, of U.S. authorities. While the U.S. has offered friendly assistance and partnership to the Castro government, Hernández’s letter and its publication from a U.S. prison reinforces the idea that a largely unregulated extractive economy controlled by foreign interests must be maintained if Honduras is to prosper—a proposition clearly contradicted by the experience of the past 12 or more years.

Arrest of Juan Orlando Hernández. [Source: getindianews.com]

Significantly, Hernández’s letter to the Honduran people also seems to reinforce a basic policy assumption of the Biden administration’s initiatives for curbing emigration from Central America by supporting more foreign aid and investment in business as usual. It seems that the U.S. and other powerful interests continue to promote the same remedy that has sickened the patient.

Hondurans fleeing poverty and violence. [Source: jimbakkershow.com]

One might think that, if the United States were serious about curbing emigration from Honduras, it would embrace and support the efforts of the Castro government to make the transition to a political economy that actually enables Hondurans to work for themselves and their families instead of schooling them in dependence on foreign interests. Instead, the United States and the powerful foreign and Honduran interests that profit from the country’s colonial dependency are hard at work threatening, resisting and undermining almost every impulse and initiative for change from the new government or the Honduran people.

The Dilemma of Ongoing Violence

The Castro government has pledged to curb violence, but it faces the entrenched interests of powerful landowners, foreign corporations and politicians and activists of Hernández’s National Party, many who still control municipalities and regions of the country and have close ties to corrupt police and gangs. Police still engage in the eviction of poor communities at the behest of powerful and wealthy interests, and the criminalization of peasant and local community leaders who try to stop the theft of their land. It is proving difficult to combat a corrupt system that has had 12 years to grow. Violent incidents, threats, disappearances and assassinations continue.

Shortly after its inauguration in January 2022, the Castro government formed a Presidential Commission to investigate and respond to land conflict and violence against peasant communities and groups in the Aguán Valley. The conflicts arise in large part because of the often illegal and violent attempts of large landowners and corporations to take land from peasant communities and cooperatives.

The openness of the Castro government to assist peasant groups has generated new energy for these groups, but also a backlash from large landowners and corporations that takes the form of an increasing number of assassinations of peasant leaders and members of peasant organisations, according to the Honduran Centre for the Study of Democracy (CESPAD) and others.

Harassment and attacks against Indigenous and other rural communities over land and resource control continue in many parts of the country, including the north coast department of Atlantida, where powerful interests use hired gunmen (sicarios) to threaten members of local groups belonging to the National Confederation of Rural Workers (CNTC). There are too many incidents of this kind to detail here.

[Source: pbicanada.org]

Some Hondurans see the roots of such violence in the interests behind the current extractive economy and the failure, so far, of the government to control unregulated extractive industries. Joaquín Mejía, a prominent Honduran human rights lawyer, said the new government was partially responsible for the murders inasmuch as it had failed to suspend or cancel the illegal mining concessions granted by the former regime.

Joaquín Mejía [Source: wp.radioprogresohn.net]

Over the past decade Honduras suffered one of the highest rates of femicide in the world. Despite the Castro government’s pledge to address and reduce the

killing of women and other gendered violence, such violence has continued and even increased in the past months.

Some remaining members of the National Party in Congress continue to use obstruction and accusation to stop most attempts to repeal laws and policies of the previous government that encouraged corruption and impunity. There is a more sinister threat in this, as well.

In October 2022, a National Party member of the Congress issued a call for Hondurans to put on their white shirts, a reference to 2009 when supporters of the coup d’état wore white shirts. This was a not-so-veiled call for a coup against the Castro government.

The nationwide network or system of interrelated actors and interests that rely on violence and intimidation to accomplish their goals is based on relationships of collusion among corrupt police, criminal gangs, drug traffickers, PN activists, powerful landowners and those with vested interests in extractive industries, and their security guards, a network of corruption described in a 2017 report from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

This interrelated network of interests and dependencies allows the powerful and prominent to use hired assassins to do the actual dirty work. Political and human rights assassinations can be made to seem like common crimes. This interrelated network of interests has not substantially changed since it formed under the former post-coup governments.

Its underpinning was widespread impunity for the perpetrators. The Hernández government and the National Party in Congress revised the Honduran Criminal Code to weaken the punishments for actual criminal behaviour while expanding the categories of popular protest and resistance that were defined as criminal behaviour, essentially turning the criminal justice system on its head—codifying a system of rewarding the perpetrators and blaming the victims. The Castro government has been working to repeal such laws and is faced with the enormous and dangerous task of trying to dismantle this system of violence, corruption and impunity.

The ongoing violence cannot be understood simply as a series of random or unconnected incidents. This violence serves several purposes. It targets and eliminates individuals who in any way contest, contradict or hinder the workings of the network of corruption. Individuals targeted for assassination can include local community leaders who try to protect the land and resources of the community from extractive projects. Or investigative journalists uncovering corruption. Or local leaders and activists of the government’s Libre Party. Or human rights defenders. Or women and leaders and members of the LGBTQ community. Violence can also take the form of threats, illegal evictions, repression and criminalization of communities that stand in the way of lucrative projects.

Investigation of death of community activist. [Source: processo.hn]

Eliminating these individuals and communities weakens the Castro government’s ability to fulfill its promised agenda, inasmuch as it eliminates some of Castro’s natural allies. The campaign of violence weakens the new government by creating a sense of chaos, and a government powerless to provide protection and stability. Creating chaos and fear is calculated to destroy people’s hopes in the Castro government.

The Dilemma of Dependence on the Security Forces

Some of these recent incidents reflect another major dilemma for the Castro government: its dependence on the country’s security forces. This poses concerns because of the role the security forces have played in recent Honduran history. The corrupt and dictatorial Hernández government relied on the military and the police to enforce its will and to enable its corruption.

The security forces were implicated in aiding the cover-up of assassinations, the unlawful eviction of communities at the behest of powerful corporations and landowners, and the brutal repression of peaceful popular protests. But the Castro government must do something to reduce gang and drug-trafficking violence and to address some other seemingly intractable problems such as environmental degradation and illegal land seizures. Using the security forces to address these problems is a temptation in a context where solutions and relief are demanded and are needed quickly.

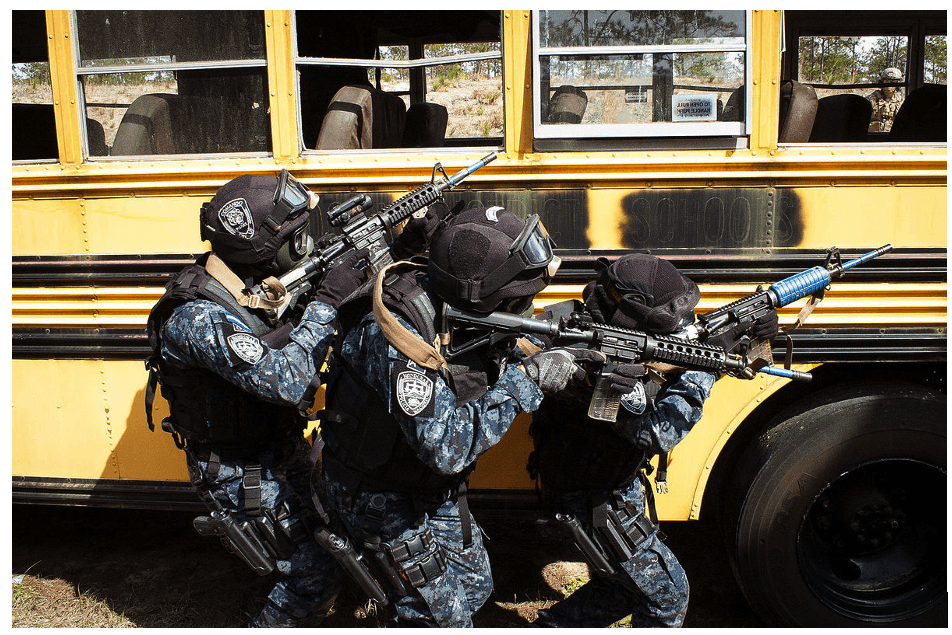

Honduran security forces have been implicated in their share of human rights crimes. This begs the question of how a progressive government should use them. [Source: ticotimes.net]

The Castro government pledged to disband the Military Police, reduce the power of the military, and clean up corruption in the National Police, but it has been hard for many Hondurans to see much progress toward these goals. The “state of exception” that the Castro government declared deploys the police and the military to enforce this.

But human rights leaders and others have expressed concern about the use of the security forces to combat extortion in certain cities since it provides the military and the police with yet another arena for increasing their hold over Honduran society and reflects the weakness of the government and civil society to deal with the problem. The Honduran military has in recent history staged coups against civilian governments it did not like.

After several decades of a rampant extractive economy—mining (including hundreds of broad mining concessions, some using open-pit mining with cyanide), as well as logging, plantation agriculture, tourism—Honduras faces serious environmental degradation. Mining and palm oil enterprises have also invaded legally protected ecological reserves such as the Carlos Escaleras National Park.

The San Pedro River, in the Carlos Escaleras National Park, was one of the many rivers under threat of devastation by open-pit mining. [Source: greenleft.org.au]

Local communities that have tried to defend their environment from extractive industries continue to suffer reprisals, as the now emblematic case of Guapinol illustrates. The Castro government plans to use the military to form “Green Brigades” to enforce environmental laws and reduce illegal land practices. The reliance on the military here is

particularly concerning for many communities that have long endured the presence of the military as an occupying force in the service of the same powerful interests that are largely responsible for extractive destruction.

The close relationship of the Honduran military to the U.S. military has long been a source of concern about the very sensitive issue of sovereignty. The Castro government raised the hope that Honduras would be able to assert its independence in the face of strong pressures from the United States. This would be a major feat, given the history of U.S. influence over Honduran life. This concern over national sovereignty was exacerbated during the years of the Hernández government, and it continues unabated. Within this concern is the ongoing dilemma of how to reduce corruption and criminality in the security forces and change their entire ethos.

U.S. soldier pins lapel on Honduran trainee at the Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras. [Source: jtfb.southcom.mil]

Human rights leaders and many other Hondurans express serious concerns about the militarization of Honduran society. As if to heighten these concerns, the government’s proposed budget for 2023 includes an increase in funding for the security forces rather than the reduction that many expected. There is concern also that what is given to the security forces will be taken from important social services and other programs, just as it was under Hernández.

The critical response to Castro’s action can be seen clearly in this excerpt from a news report in CriterioHN, an important Honduran news outlet:

The promise to demilitarize security in Honduras remains a chimera, or at least this is evidenced by the actions of the government of President Xiomara Castro, who despite having promised to take the military off the streets, is doing the opposite by allocating them more resources compared to last year.

The Dilemma of Financing Change Without Selling the Country

All of this external and internal pressure is directed toward a Honduran government that is financially weak, dependent and vulnerable, and does not control the entire country. The past 12 years of post-coup governments, greatly increased the country’s debt (now estimated at close to 60% of the country’s GDP) while corrupt officials systematically pocketed huge amounts of state finances and starved basic social services.

The Castro government finds itself with a financial dilemma, needing money to pay the debt and to finance services such as public health and education that have been so neglected that they will require more money to restore and rebuild to adequate functioning. Sources of funding are problematic. With one of the poorest populations in the region, Honduras cannot rely heavily on taxes and fees from its own people.

Extractive industries bring in revenue, but many of these industries—mining, logging, export agriculture, tourism—also operate under contracts favourable to the investors and companies, contracts negotiated by the Hernández government, that enrich the extractors while returning little wealth to the country.

Mining actually provides only a small percentage of the country’s income, but it is protected by the powerful interests that benefit. Because Honduras has been so reliant on extractive industries, those who control them—both Honduran elite and foreign interests—wield an outsized influence in the country.

There are other sources of income for the Castro government. Foreign aid, loans and investment are available to the Honduran government. But since the government is known to be in need of money, it seems to be in no position to negotiate for favourable terms. The problem here is to distinguish what assists self-reliance and change from what reinforces dependency and “business as usual.”

The inherent danger with reliance on this area of finance is that government plans and programs are reshaped to suit the needs of the foreign sources of income, to put reform on hold in order to attract needed income. In addition, high levels of violence, corruption, and extortion in Honduras over the past decade have been a source of concern for some potential foreign investors. For those interests that want to cripple the Castro government, chaotic acts of violence serve the same purpose of discouraging investment.

Without the funds to service the debt and address basic social needs, there is a political price to be paid for deferring change indefinitely. It is the pressure from below, from the Honduran people who elected Castro and who need or expect her government to transform at least some of the worst conditions in basic services in the country. The urgency of this demand is becoming increasingly evident in the function of daily basic services such as public health and meeting needed raises to salaries for public workers such as nurses.

Hondurans at the polls on election day in 2021. [Source: Photo courtesy of Lucy Edwards]

In 2009, the year of the coup, approximately 1,000 Hondurans left the country seeking asylum. By the later years of the Hernández government (2015-2020), as many as three hundred people may have been leaving Honduras each day, a significant number out of the total population of Honduras (approximately 9.5 million). So far, this emigration flow has shown few signs of diminishing since the inauguration of the Castro government.

Hondurans in the United States during the past 12 years have been sending back remittances to Honduras that have totalled in excess of $4 billion a year, amounting to almost 20% of the country’s income.

This situation presents a dilemma for the Castro government. The flow of remittances that Hondurans in the United States have sent back to Honduras in recent years has been a substantial support for many Hondurans, relieving some of the economic pressure on some Honduran families. This is very real income for Honduras. When the Castro government was taking office early in 2022 and wondering how to finance both the country’s debt and meet its public social needs, remittances seemed like an important resource.

But this boost to the economy also comes with significant risks and costs. Remittances depend on several factors not under the control of the Honduran government, including fluctuations in the U.S. job market and attitudes and policies toward immigrants in the United States. The flow of remittances is thus unreliable over time.

The cost of this flow of people out of Honduras is evident. It represents a significant loss of youth, energy and creativity out of the country—a negative flow of social capital. This social capital is one of the major resources Honduras must have and retain if the promises of transition and reform under the new government are to become reality.

Such a large emigration also represents yet another sign of the dependency of Honduras on the United States as its benefactor. The large emigration to the U.S. allows the United States to use immigration policy and the image of migrants as a weapon to control and hold Honduran governments accountable. The fate of Honduran e/immigrants becomes a bargaining chip in the relationship between Honduras and the United States.

The Administration’s Call to Action initiative promises millions of dollars to Honduras and other Central American countries to promote investment, attract foreign corporations and create jobs, supposedly to create conditions for Hondurans to remain in Honduras. But to receive this aid, it is clear that the Castro government must agree to do nothing to seriously alter or challenge the current dominance of foreign corporations and “business as usual.” To some Hondurans and foreign observers, this seems like the same failed policy again—or worse, a form of extortion.

There is also the serious problem of immigrant child labour in the United States. As the number of children and teenagers immigrating to the U.S. from Honduras and other Central American countries has exploded in the last few years, individuals posing as “sponsors” have trafficked children and teens into dangerous and difficult jobs, violating U.S. child labour laws and keeping these immigrant youth in debt servitude, as a February 26 report in The New York Times reveals.

Many of these young people are under immense pressure to make money to send home and to pay back their “sponsors.” Many die through work-related accidents or illnesses. So far, U.S. authorities and agencies charged with the welfare of immigrant children do not seem to have been able to gain control of the situation. All of this raises questions about the real value of remittances coming from child labour. Cynics point out that child labour is common in Central America, but that is another of the realities that the Castro government must work to change.

Child labourers in Honduras. [Source: rebellion.org]

The Problematic Relationship with the United States

For 150 years, the United States has influenced and sought to control the economic and political life of Honduras. In the age of U.S. expansionism and empire building, Honduras became a colony.

U.S. mining, and then banana and fruit company interests that gained such control over Honduran political life in the early 20th century were followed by the strengthening of relationships between the militaries of the two countries beginning in the 1950s. Civilian governments have come and gone in both countries, but the military relationship and collaboration has remained. The U.S. turned Honduras into its chief vassal state in the region, and the base for projecting U.S. military power. So dominant was the U.S. presence in the 1980s that Honduras was called the “USS Honduras,” and one Honduran congressman said, “Everyone knows Honduras is run by the U.S. Embassy. Honduras is an occupied country…”

Honduran governments, controlled by a small political and economic elite, found it to their advantage to keep the country “open for business,” especially for U.S. and other foreign investment.

Honduran soldiers in the 1920s who were trained by the U.S. [Source: latinamericanmusings.wordpress.com]

The country alternated between periods of military rule and weak civilian government. Honduras was a nation with weak institutions and a powerful elite aligned with U.S. interests, despite the misgivings of many Hondurans about the loss of national sovereignty under the control of the U.S. Embassy.

Honduran soldiers operate a mortar for members of the U.S. Army 82nd Airborne Division during a joint exercise, March 1988. [Source: revcom.us]

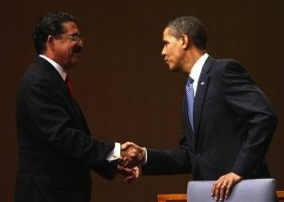

In the past decade, U.S. involvement in Honduran affairs has continued. Consider the response of the Obama administration to the coup in June 2009 that deposed Manuel Zelaya’s mildly reformist government. After a brief delay, the

U.S. recognized the post-coup government in the interest of moving on and promoting “business as usual.” As the Hernández government became ever more mired in human rights abuses, corruption and violence, the State Department continued to certify that the country was making progress in democracy and human rights, ignoring the mountain of evidence to the contrary.

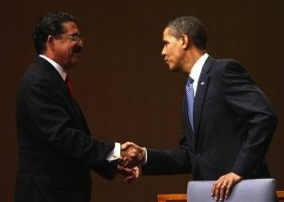

Obama shakes Manuel Zelaya’s hand at the Summit of the Americas not long before Obama backed a coup against him. [Source: latinamericanmusings.wordpress.com]

When Hernández finally left office last January, the U.S. requested his extradition on charges of drug trafficking. Many Hondurans breathed a sigh of relief, but they also saw this as another sign of the colonial-style relationship of their country to the United States. Some asked, “Why did we need the U.S. to indict Hernández? Why couldn’t our own institutions do it?”

Some Honduran human rights leaders argued that the U.S. indictment of Hernández, who was for so long a staunch U.S. ally, was an effort to clean an embarrassing image so that the exploitative reality could continue as usual with a cleaner, friendlier face.

The U.S. military presence in Honduras, the training of Honduran military in the U.S., and the joint military training exercises since the 1980s have been a part of the Honduran relationship to the U.S. for years and has expanded to include the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Currently, the U.S. is promoting more “security” agreements with the Castro government.

Meanwhile, the U.S. is constructing a massive new embassy in the heart of the Honduran capital. The current embassy complex is already large, and the new one raises questions about its actual purpose in a country with a population of fewer than ten million. What agencies, offices and military units might be housed in this new embassy? The workers building it have been on strike for several months, with complaints of working conditions and owed pay against the contractor hired by the U.S.

Blueprint of the new U.S. embassy compound in Tegucigalpa. [Source: ai-architect.com]

The United States is committed to the idea that it needs Honduras as one of its primary allies in the region, and one that is, conveniently, next door to Sandinista Nicaragua.

From the viewpoint of Washington, Honduras cannot be allowed to loosen its ties with the U.S. and move toward the sort of people-oriented political economy espoused by, for example, Nicaragua. This thinking—this fear—drives reaction to what the Castro government is trying to accomplish.

The Dilemma of Fractured Solidarity

Honduran human rights leaders have said repeatedly over the past decade that they welcome external solidarity, and that it can be of much help. But the pressures and dilemmas exerted on the Xiomara Castro government as it tries to move Honduras toward a more just and liveable society threaten to create yet another dilemma, one of fractured solidarity, both internal and external. Internal solidarity with the new government comes from the support of the Honduran people for the programmes of the new government and a stake in the general direction in which the government is leading the country.

While still strong, this support is strained by an increasing perception that the government cannot deliver on its promises, that it is internally divided, or worse, that it is making compromises with the very actors and forces of the old regime—police, military, big extractive and foreign businesses, the National Party, and the U.S Embassy. Internal solidarity can give way to disillusionment, passivity, emigration, or other reactions that further weaken the government’s support.

This situation also shapes external solidarity—the solidarity of groups and organisations in Europe, the United States, Canada and elsewhere. The image of a government that cannot seem to deliver the transformations it has promised; a country in turmoil, division, and violence; and a country whose government is forced to resort to drastic and seemingly repressive measures to “fast-track” some of its promises. All this can confuse and weaken the sense of solidarity from abroad.

What are people of good will outside of Honduras to think of what is happening in the country? A confusing and negative image is easily amplified by news media controlled or influenced by the forces (internal and external) that do not want change in Honduras. Perception and news media play critical roles in this shaping and fracturing of solidarity.

This sort of weaponization depends on: (1) portraying a distorted picture of friendly and legitimate criticism as a mass movement against the Castro government as a whole; (2) suggesting that the problems and “failures” of the Castro government are the result of its own policies rather than the entrenched legacy of the previous government aided by the U.S.; (3) erasing the historical context of U.S. control and interference in Honduran life; and (4) using terms such as human rights and democracy selectively to reshape and re-direct sentiments of support to serve the purposes of the U.S and other vested interests instead of the Honduran people.

By these means, solidarity can be weakened, diverted or invited to support narrow interests determined in Washington and foreign corporate board rooms without ever revealing these interests. Hondurans are wise to the ways that U.S. administrations and agencies and some of their own governments have tried to deceive, co-opt and suppress their aspirations. But the situation for Honduras at this moment raises concerns that both internal and external solidarity with the Castro government may become strained, if not endangered.

What Next?

The interrelated dilemmas facing the Castro government seem to present a “damned either way” situation. The bright light for Honduras is its people. They have a long history of organised, creative and peaceful resistance to the exploitation of their land and resources and the dangers to their national sovereignty. Honduras has very active and politically astute popular organisations and a strong and independent community of defenders of human rights, local communities and the environment. Their election of the new government was another powerful action to take back their country.

At this precarious moment, what constitutes real solidarity with the Honduran people? For U.S. citizens whose primary responsibility is the actions of their own government, recognizing and working to change the role of the U.S. government and corporations in perpetuating the status quo of “business as usual” would be a primary expression of solidarity since it would address one of the primary obstacles to change in Honduras. Re-thinking the failed strategy of more foreign investment and foreign aid for large-scale extractive development in Honduras would help considerably.

Finding ways for consumer action, legal action and legislation to hold U.S. corporations and investors accountable for their practices in Honduras is a related form of much needed solidarity with the Honduran people.

Working for major reforms in immigration policy could be another form of solidarity for U.S. citizens. In this, it is worthwhile to work toward ending mechanisms and excuses for mass deportations of Hondurans and others (excuses such as Title 42).

The United States government continues to talk of “partnership” with Honduras, but the relationship is intrinsically one of dominance. After more than 150 years of assumed superiority by successive U.S. administrations, it will be a difficult challenge to significantly change this official attitude to one of real partnership. The heart of solidarity with Honduras will require a significant change in attitude and practice. The human people-to-people connection that animates solidarity will be a great asset in this effort. What happens to Honduras will tell us much about the future of Honduras, Latin America and the United States.

In contrast, these are daily hazards facing Community Journalist Carlos Choc Chub from Guatemala (second from right) and Environmental Rights Defender Reynaldo (Rey) Dominguez (on the right) from Honduras, pictured at a roundtable in London organised in November 2022 by Peace Brigades International (PBI). It has since been revealed that Reynaldo’s brother Aly was assassinated on 7th January 2023, along with Jairo Bonilla, as they both attempted to defend Honduras’s Guapinol River – read more details of the killings in Honduras in the article preceding this.

In contrast, these are daily hazards facing Community Journalist Carlos Choc Chub from Guatemala (second from right) and Environmental Rights Defender Reynaldo (Rey) Dominguez (on the right) from Honduras, pictured at a roundtable in London organised in November 2022 by Peace Brigades International (PBI). It has since been revealed that Reynaldo’s brother Aly was assassinated on 7th January 2023, along with Jairo Bonilla, as they both attempted to defend Honduras’s Guapinol River – read more details of the killings in Honduras in the article preceding this. Carlos has faced threats to his life and the lives of his family. Homes in his community regularly get raided and at times he can’t stay at home. For Carlos this started in 2017 after photographing and reporting on violent repression by Guatemalan security forces of a demonstration during which an unarmed protester, Carlos Maaz, was killed. The protest was organised by local fishermen against the contamination of Lake Izabal, the largest freshwater lake in Guatemala, by the Fenix ferro-nickel mine.

Carlos has faced threats to his life and the lives of his family. Homes in his community regularly get raided and at times he can’t stay at home. For Carlos this started in 2017 after photographing and reporting on violent repression by Guatemalan security forces of a demonstration during which an unarmed protester, Carlos Maaz, was killed. The protest was organised by local fishermen against the contamination of Lake Izabal, the largest freshwater lake in Guatemala, by the Fenix ferro-nickel mine.