Rights Action

December 16, 2024

Rights Action is a US and Canadian non-governmental organisation that supports the struggles of grassroots and Indigenous communities in Central America, especially those in Guatemala and Honduras. It lobbies on their behalf and exposes the violent roles of the US and Canadian governments in bolstering the domineering and violent neocolonial behaviour of North American transnational corporations that extract the resources of Central American communities with no regard for the local societies, traditions or environments affected by their companies’ operations.

Letter from Panama’s ‘Little Hiroshima’, by Belén Fernandez

https://mailchi.mp/rightsaction/letter-from-panamas-little-hiroshima

U.S. owes reparations to survivors of 1989 “just cause” invasion of Panama

This week, Rights Action will share articles remembering the December 20, 1989 U.S. “just cause” invasion of Panama and slaughter of perhaps thousands of civilians.

Connecting the dots: As the U.S.-led west continues to support and legitimize Israel’s ethnic cleansing genocide in Palestine, and expansionist aggression in neighboring countries, it is never too late to keep on telling truth about and demanding justice and reparations for victims of previous U.S.-led imperialist invasions and aggressions.

*******

Letter from Panama’s ‘Little Hiroshima’

I paid a visit to El Chorrillo almost exactly 34 years after the US turned it into a ‘Little Hiroshima’ for a ‘Just Cause’.

By Belén Fernández, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan 2024

https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/1/24/letter-from-panamas-little-hiroshima

Once upon a time, the United States was good buddies with a fellow named Manuel Noriega, a longstanding CIA asset and the dictator of Panama in the 1980s.

Then one day, Noriega outlived his usefulness as an imperial lackey and needed to be sent packing. And so with a straight face, the gringos accused him of the unpardonable offence of drug trafficking and undertook to overthrow him in 1989.

This was funny; after all, since at least 1972 the US had known about – and intermittently benefitted from – Noriega’s links to the drug trade. Furthermore, the US president spearheading the dictator’s removal was none other than George H W Bush, the very same George H W Bush who as director of the CIA in 1976 had ensured Noriega’s preservation on the agency payroll.

Anyway, boundless hypocrisy has always been America’s strong point. And it was once again on full display in the selection of the name for the unilateral US military operation to bring “democracy” to Panama by killing a bunch of Panamanian civilians, pulverising the impoverished Panama City neighbourhood of El Chorrillo to the extent that local ambulance drivers began to call it “Little Hiroshima”, and hauling Noriega off to Miami.

Following some heavy contemplation, the preliminary title “Operation Blue Spoon” was changed to “Operation Just Cause”. The late Colin Powell, who was then serving as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, explained in his 1995 autobiography, A Soldier’s Way, that he preferred the “inspirational ring” of the revised title – and the fact that “even our severest critics would have to utter ‘Just Cause’ while denouncing us”.

Plus, Powell reasoned, Blue Spoon was just “hardly a rousing call to arms… You do not risk people’s lives for Blue Spoons”.

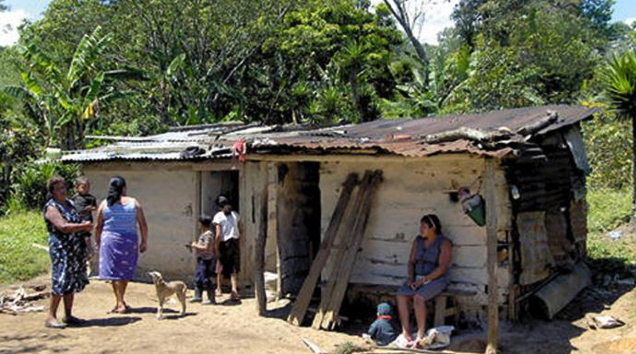

Of course, the change in labelling was irrelevant to the civilian inhabitants of El Chorrillo – the site of Panama City’s central military barracks – who bore the lethal brunt of the ensuing “just cause”. Then again, it wasn’t their lives that Powell was concerned about risking. Just after midnight on December 20, 1989, the neighbourhood was jolted awake by the fanatical show of US firepower that would quickly earn it the moniker “Little Hiroshima”.

As US General Marc Cisneros, one of the operation’s commanders, admitted in 1999 on the 10th anniversary of the invasion, the military’s approach was probably a bit overzealous: “We made it look like we were battling Goliath… We have all these new gadgets, laser-guided missiles and stealth fighters, and we are just dying to use that stuff.”

Almost exactly 34 years after the fun with gadgets, on this past New Year’s Eve, I paid a visit to El Chorrillo, taking an Uber down the hill from a friend’s house in the Quarry Heights area of the Panamanian capital – the US military’s former command centre in the Panama Canal Zone. My plan to wander around and photograph El Chorrillo’s assortment of anti-American graffiti was thwarted when the female Uber driver, citing concerns for my safety, insisted on delivering me into the care of two policemen standing on a street corner.

Too young to have experienced the 1989 invasion, they proved chatty albeit not so confident in their own crime-fighting prowess: “Sometimes we’re standing here and people are getting robbed in the supermarket next door.”

One of the cops escorted me down the street to view the diminutive statue of a crouching human, a monument to those killed during Just Cause. Estimates of Panamanian civilian deaths during the operation range from a few hundred to many thousands, depending on whether you ask the United States or human rights organisations.

To politely extricate myself from the company of the two policemen, I asked whether they knew anyone who might want to talk to me about the invasion. As a matter of fact, they said, there was an older man named Hector who lived nearby and was the only resident of El Chorrillo to have 24-hour police protection on account of four gang attempts on his life. Hector knew all about 1989.

A few phone calls were made and I was handed off to a different set of police, who waited with me in front of Hector’s dilapidated apartment block. A young boy shot at all of us with a triceratops-shaped toy pistol, and a group of giggling young girls asked me the English words for “knife”, “dirty teeth” and “Santana” – the last name of one of the cops.

Then it was into Hector’s cramped kitchen, where preemptive New Year’s fireworks outside provided a fitting soundtrack to the subject at hand. Seventy-seven years old and in possession of a certain joie de vivre that is perhaps inaccessible to those of us who have not survived four assassination attempts, Hector unearthed a tattered 33-year-old newspaper – published on the first anniversary of Just Cause – and encouraged me to peruse the photographs of corpses and mass graves.

As it turned out, Hector had not been present during the invasion, having been expelled from Panama for political reasons some months earlier. He returned to the country in February 1990, shortly after Just Cause had been brought to its swift and triumphant close, and became a leader in the fight to prevent Panama’s new “democratic” powers that be from appropriating El Chorrillo for their own lucrative ends.

In Hector’s words, the mentality of the new opportunists was: “Let’s get the chorrilleros out of there since the gringos already burned everything.”

And burn they had, the fire spreading easily as most of the houses were made of wood. Many, incidentally, had decades previously housed the workers who built the Panama Canal – another crowning achievement in the United States’ lengthy history of imperial exploitation. While then-US Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney would claim that Just Cause had “been the most surgical military operation of its size ever conducted”, you can’t really have a surgical Hiroshima.

Fishing a pamphlet by Panamanian sociologist Olmedo Beluche out of the clutter on his kitchen table, Hector set about reading to me from the section on aircraft and armaments used in Just Cause that were then deployed on a massive scale in the first Persian Gulf war: F-117 stealth bombers, Blackhawk helicopters, Apache and Cobra helicopters, 2,000-pound bombs, Hellfire missiles, and so on.

Indeed, as historian Greg Grandin has emphasised, the road to Baghdad “ran through Panama City”, with Just Cause marking the start of an “age of preemptive unilateralism, using ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’ as both justifications for war and a branding opportunity”.

In 2018, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ruled that the United States should “provide full reparation for the human rights violations” committed during Operation Just Cause, “including both the material and moral dimensions”. You can guess how that’s panning out.

As I made my way back to Quarry Heights on New Year’s Eve, I passed a memorial to Martyrs’ Day – a reference not to the martyrs of El Chorrillo but rather to the martyrs of January 9, 1964. On this day, US forces in the Canal Zone killed at least 21 Panamanians during riots in the aftermath of an attempt by Panamanian students to raise Panama’s flag next to the US one.

Sixty years on from Martyrs’ Day, the US still hasn’t managed to kick its habit of killing people – including indirectly in the Gaza Strip, a “little Hiroshima” if there ever was one. Forget “moral dimensions”; the US operates in a strictly iniquitous one.

(The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance. Belén Fernández is the author of Inside Siglo XXI: Locked Up in Mexico’s Largest Immigration Center (OR Books, 2022), Checkpoint Zipolite: Quarantine in a Small Place (OR Books, 2021), Exile: Rejecting America and Finding the World (OR Books, 2019), Martyrs Never Die: Travels through South Lebanon (Warscapes, 2016), and The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work (Verso, 2011). She is a contributing editor at Jacobin Magazine, and has written for the New York Times, the London Review of Books blog, Current Affairs, and Middle East Eye, among numerous other publications.)