By Martin Mowforth

Followers of the monthly additions to The Violence of Development website will already be aware that the conditions of human life in Honduras are pretty much unliveable for the majority of the country’s population. Witness:

- The epidemic of homicides over the last ten years.

- The wave of migrant caravans setting off from Honduras for the United States over the last three years.

- The growing local and national dominance of gangs and their threats and extortion of Hondurans trying to run their own businesses.

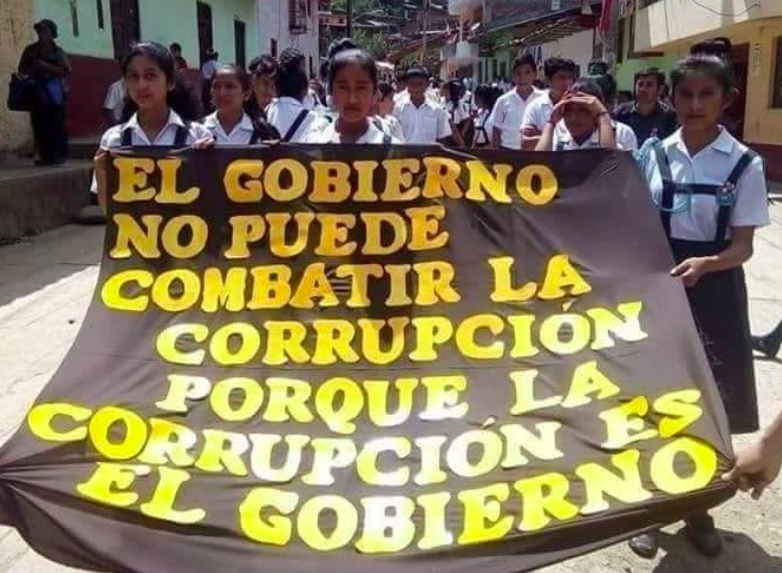

- The corruption of the national government, seemingly run as a facilitator of organised crime.

- The attitude of transnational corporations towards Honduran people, reflecting more the behaviour of crime syndicates than legitimate businesses.

- The dispossession of the Garífuna, the Lenca and other Indigenous groups of their land and their resulting displacement.

- The likelihood of threats and violence towards those who protest against these conditions.

- The growing wave of poverty.

- The growing wave of unemployment.

- The growing wave of hunger and malnutrition.

- The privatisations of previously public services.

- The defunding of public services.

- The regular annual increase in funding for the repressive Honduran security forces.

- The extraction of national and natural resources by foreign companies.

Add to this list the passage of Hurricanes Eta and Iota in November and the Covid-19 pandemic, and nobody should be surprised that so many Hondurans seek to flee the country to anywhere they may find better and less violent opportunities. On 10th December [2020] a caravan of over 400 people left Honduras for the United States searching for a new life, but they were prevented from going further at the border with Guatemala. In mid-December it was reported that hundreds of Hondurans were planning to leave San Pedro Sula (the country’s second town) as another migrant caravan in mid-January. They will presumably already have considered the possibility of being stopped at the border and may well have considered alternative routes and means. In mid-January [2021] the formation of the caravan was reported to be 7,000 – 9,000 strong and to have passed through the Honduras–Guatemala border, but also to have been prevented from going any further and scattered[1] – as I write.

Telesur’s correspondent in Honduras, Gilda Silvestrucci, reported that the pandemic had given rise to a wave of violence in the country affecting the most impoverished and vulnerable areas and people. “In Honduras the economic crisis generated by the pandemic and the hurricanes will bring new migratory caravans in January 2021.”[2]

Miriam Miranda, a Garífuna land, environmental and human rights defender and Coordinator of OFRANEH (Black Fraternal Organisation of Honduras), described the situation thus: “We live in a country of eternal emergencies. We have no time for anything else. US and Canadian supported coups d’état. Pandemics. Hurricanes and tropical storms. Rapacious, murderous and corrupt governments backed by the US, Canada and transnational companies. We need to construct another society and State.”[3]

In amongst the bad news of state failure, violence, corruption and killings, mid-December brought welcome relief with the news of the arrival and assistance of a brigade of Cuban doctors to tend to the victims of Hurricanes Eta and Iota. Spokesman for the brigade, Dr Carlos Alberto León Martínez, explained that they were also prepared to tend to Covid-19 patients. The brigade was made up of 11 doctors, five graduates in nursing, five specialists in hygiene and epidemiology, an administrative director and three service workers.[4] Given the strong control of the Honduran government by the US and by organised crime, one might wonder why the government would allow a brigade from Cuba to enter the country; but Cuba began its medical cooperation with Honduras in 1998 after Hurricane Mitch struck the region. It has maintained that relationship with the Honduran medical establishment since that time and by 2019 more than 2,000 Cuban doctors had provided more than 29 million medical services and 800,000 major surgeries within Honduras.[5]

Apart from the 91 deaths and countless people left homeless by Hurricanes Eta and Iota, schools, public buildings, bridges and roads were also destroyed or damaged. Many floods and landslides occurred and over 70 communities were left without electricity.

On 22 December, the Central Bank of Honduras (BCH) and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL by its Spanish initials) estimated that the country’s losses due to the two hurricanes and the pandemic were standing at over $4 billion. The CEPAL report detailed the goods not produced, the services not rendered, the damages to infrastructure, buildings and production, and the cost of reconstruction. The loss and damage costs caused by the pandemic and the hurricanes were estimated at $2.3 billion and $1.9 billion respectively.[6] At the end of 2020, the Central American Bank of Economic Integration (BCIE by its Spanish initials) made $652 million available as bonds for the reconstruction of Honduras, and announced the availability of another $1 billion of bonds. Dante Mossi, the Executive President of the BCIE, was reported as saying that the support for the government “will not necessarily lead to sovereign indebtedness,”[7] but the support will be issued in bonds to the banks so that they have the necessary liquidity to enable them to make loans to companies and cooperatives. If that doesn’t lead to indebtedness for the government, it will certainly lead to indebtedness for the Hondurans who take loans from the banks.

Honduras has an appalling record of killing, jailing or legally preventing land, environment and human rights defenders from protesting against some form of economic activity that will displace them and the communities they represent. In September 2019, eight anti-mining protesters were sent to jail as preventive detention. They were detained for defending the headwaters of the Guapinol and San Pedro Rivers, on which their communities depend, from the threat of pollution by a mining project owned by the Honduran mining company Inversiones Los Pinares.

The eight are: Porfirio Sorto Cedillo, José Abelino Cedillo, Orbin Naún Hernández, Kelvin Alejandro Romero, Arnol Javier Aleman, Ewer Alexander Cedillo, and Daniel Márquez. They have spent 15 months in preventive detention and another Committee member, Jeremías Martínez Díaz, has been in the same situation for two years, since December 2018. These are the Guapinol Eight. Just before Christmas [2020], Judge Zoë Guifarro refused to free the men and refused to accept their legal team’s appeal. The decision was described as totally illegal. Edy Tábora, a member of the legal team, said that this “reaffirms the pact of impunity between the company, Inversiones Los Pinares, the Public Prosecutor and the judiciary.”[8] The owners of Inversiones Los Pinares are Lenir Pérez, previously linked with other mining-related abuses, and Ana Facussé, daughter of the late palm oil magnate Miguel Facussé whose economic activities have been linked with violence, assassinations and drug trafficking.

18th January [2021] marks 6 months since the forced disappearance of the Garífuna Five. The five are Alberth Sneider Centeno Thomas, a 27 year old community activist who has advocated for the Honduran government to compensate the Garífuna people for stolen land, Milton Joel Martínez Álvarez, Suami Aparicio Mejía Garcia, Junior Rafael Juárez Mejía and Gerardo Mizael Rochez Cálix.[9] All are members of the Fraternal Organisation of Black Hondurans (OFRANEH). All were abducted by armed men identified as agents of the Honduran Investigative Police Agency (DPI) and have not been seen or heard from since. OFRANEH has been demanding that the Honduran government comply with an Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) order to clearly demarcate their land and ensure their right to it.[10] Given this clear example of state terrorism, it never ceases to amaze that the governments of the United States, Canada and the UK continue to support the organised crime syndicate of President Juan Orlando Hernández which governs Honduras.

On 4th January [2021], former Honduran President Manuel Zelaya, who was deposed by a military coup in 2009 and is now coordinator of the LIBRE Party (Freedom and Refoundation Party), published a report on the social and economic conditions prevailing in the country. The report noted a 3 year period of sustained output decline, a very high level of indebtedness to foreign institutions, and a high level of corruption. The public debt increased from $3.2 billion in 2009 to $16 billion in 2020. The report warned that “This accelerated indebtedness, which is suffocating the economy …., cannot be sustained without falling into the vicious circle of further increasing debt to pay off debt.”[11]

All is not well in Honduras – an under-statement if ever there was one.

[1] El Economista, 18 January 2021, ‘Guatemala disuelve con el uso de la fuerza a caravana migrante hondureña’, El Economista y EFE.

[2] Gilda Silvestrucci, 18 December 2020, ‘New Caravans of Honduran Asylum-Seekers Expected as Crisis Continues’, Telesur.

[3] Rights Action, December 2020, ‘The Normalcy of “Eternal Emergencies” in Guatemala and Honduras’, Rights Action December 2020 Newsletter.

[4] Telesur, 16 December 2020, ‘Honduras: Cuba Sends Medical Brigade to Assist Eta, Iota Victims’.

[5] Ibid.

[6] El Economista, 22 December 2020, ‘Pandemia y huracanes dejan pérdidas a Honduras por $4,140 millones’, El Economista, taken from Agencia EFE.

[7] El Economista, 10 December 2020, ‘BCIE anuncia $1,000 millones para la reconstrucción de Honduras’, El Economista, taken from Agencia EFE.

[8] Jen Moore, 25 December 2020, ‘No Holiday for Honduran Anti-Mining Activists’, Counterpunch.

[9] The Violence of Development website, 20 August 2020, ‘The Garífuna Five’, https://theviolenceofdevelopment.com/the-garifuna-five/

[10] School of the Americas Watch, 18 January 2021, SOAW newsletter.

[11] Telesur, 4 January 2021, ‘Ex-President Manuel Zelaya Decries Social Situation in Honduras’.