Category: Troublesome Gangs

How gangs can affect everybody

Gang culture in El Salvador

By Martin Mowforth

In April this year (2019), it was reported in El Salvador that municipal employees who provide local services such as rubbish collection in the town of Apopa had stopped work because of threats from local gang members.

The threats began with two gang members who threatened the fee collectors from the almost 2,500 market stall holders, from which the municipality gains between $1,200 and $1,500 each week. Threats were later extended to burial services at the local cemetery where work also stopped meaning that three families had to bury their relatives in other municipalities. Also affected were rubbish collection services and one crucial bus service.

Local mayor, Santiago Zelaya, organised a group of volunteers to collect the rubbish with accompaniment by the National Civil Police. Initially only three police patrols were granted and other services could not be guaranteed by police protection. Mayor Zelaya said, “In view of this situation with reduced municipal ability, we request that the security forces support the progress and development that the municipality has made.”

It is believed that the gangs became short of money following the holiday period (December – February) and that the threats stemmed from their need to raise funds. Four gangs operate in Apopa (only 20 km from the capital San Salvador) where schoolchildren and students, as well as businesses, have to be extremely wary as they travel to and from their studies on account of the danger of approaches by gang members.

The Barrio 18 gang is thought to be responsible for the threats. The gang had an agreement with the previous mayor who is now languishing in jail along with several gang members.

Between the 1st January this year and the 25th February, fifteen assassinations were committed in Apopa, the same number as were committed during the whole of 2018.

On 30th January this year I participated in a visit to the Comunidad Romero, close to the town of Apopa. The visit was organised by the Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad (CIS, Centre for Exchange and Solidarity), and our group discussed the problems of living there with a group of impressive young people who spend much of their time trying to avoid being approached and hassled by gang members. There is little work available and so young people who do not make the grade in school generally hang around on the streets where they are highly vulnerable to approaches by gang members.

The main street in Distrito Italia where the community is located, is run by the Barrio 18 gang on one side and by the Mara Salvatrucha on the other. Young people on their way to school or to get the bus to go into Apopa or San Salvador are particularly vulnerable to these approaches, and so many of the young people from Comunidad Romero have to go the long way round to avoid such contact.

Given the lack of employment opportunities and the lack of alternative forms of development, it is unsurprising that so many young adults join the migrant caravans in search of a future.

Sources:

- La Prensa Gráfica, 14 April 2019, ‘Amenaza de pandilla en Apopa limita servicios municipales’ / ‘Gang threats in Apopa restrict municipal services’.

- Daniel Torres (El Salvador Day), 14 April 2019, ‘Pandilleros no permiten que se recoja basura en Apopa’ / ‘Gang members stop waste collection in Apopa’.

- Personal notes by Martin Mowforth from visit to Comunidad Romero, 30 January 2019.

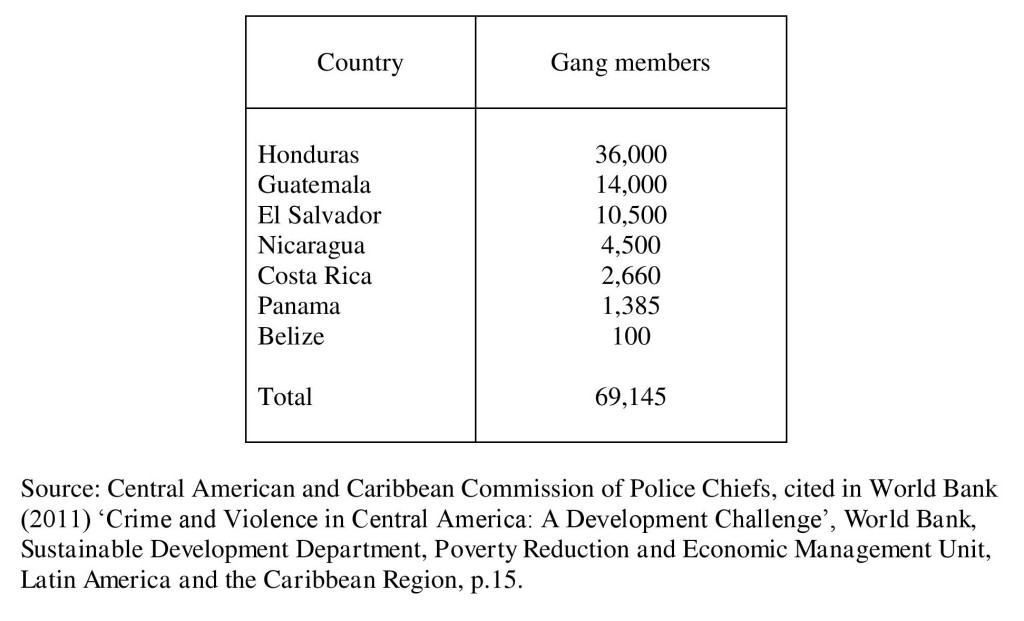

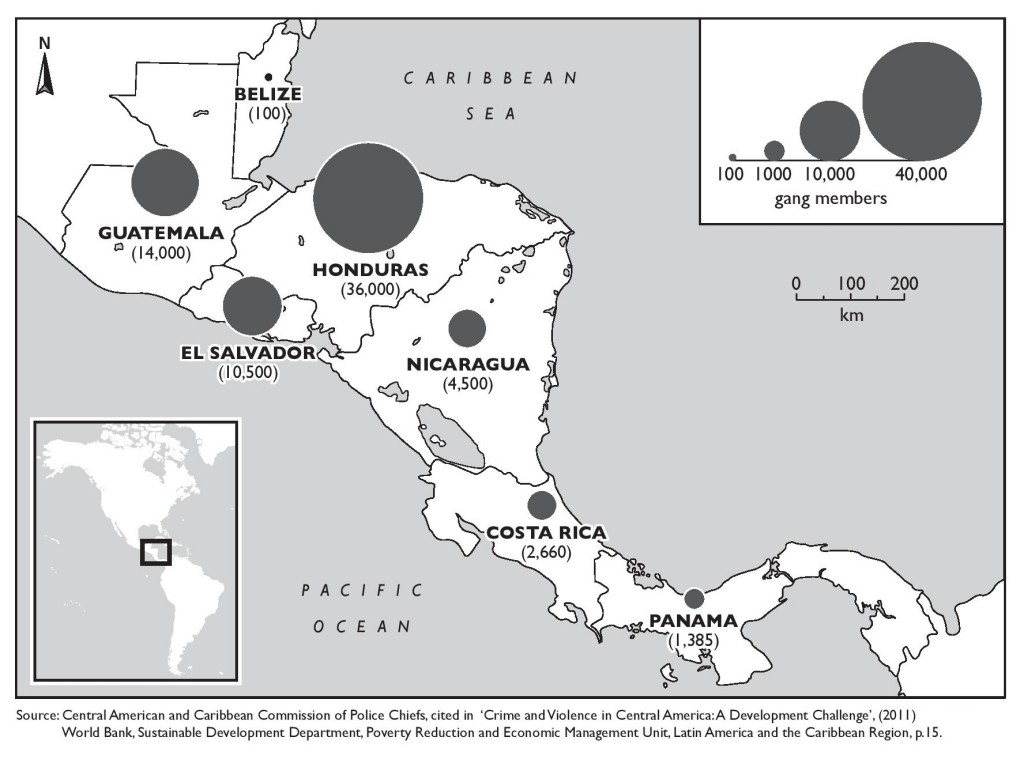

Estimates of gang membership, Central America

The following map appears as Figure 9.1 in the book (page 189)

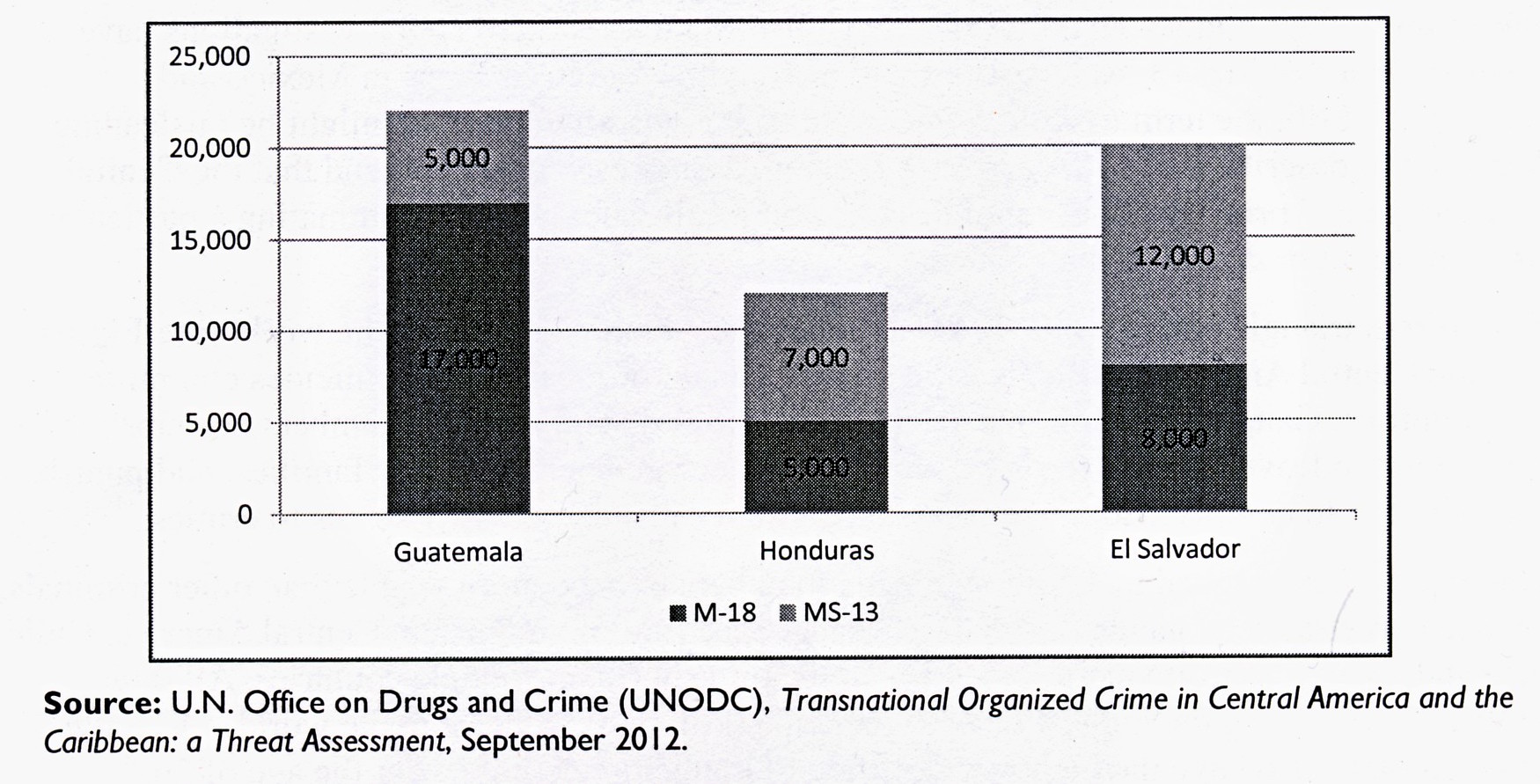

Estimated Gang Membership in the Northern Triangle of Central America, 2012

MS-13 seeks truce with the government

Reproduced from LatinoLife

January 2017

This Latino Week

by: Jim McKenna

El Salvador gang requests government dialogue

One of El Salvador’s most prominent maras, MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha), offered to dissolve itself as an organisation in return for government concessions. MS-13 stated that it wanted a dialogue on a range of matters, including political representation and amnesty. The government rejected the proposal, saying that it amounted to negotiations with criminals.

Attempts to control the gangs of Central America is not a new development; with a 2012 truce in El Salvador failing within a year of its implementation. The main difference between 2012 and now was thought to be the promise of dissolution in exchange for government promises, which was previously not offered.

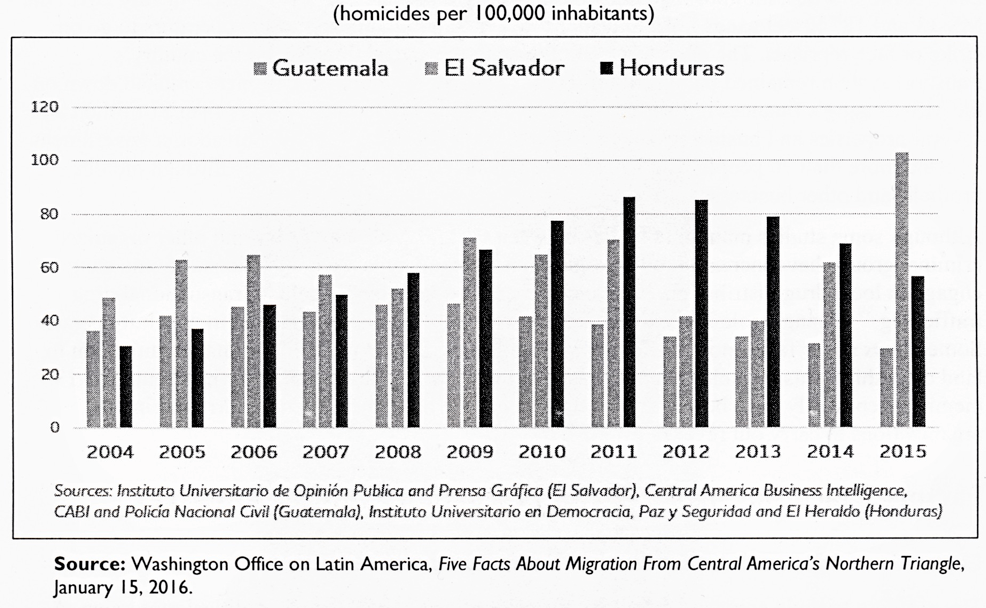

Central American gangs have historically been a problem, with U.S. deportation in the 1980s creating a situation where youth gangs would run rampant in society. Although the perceived importance of such gangs has declined in recent years, Central American cities still remain hotspots for violence, with an estimated 10 homicides a day in El Salvador this year.

El Salvador’s State of Exception

10 February 2023

The El Salvador Solidarity Network (ESNET), a UK-based network, passed on to its members an article by El Faro investigative journalists regarding the country’s current state of exception. We are grateful to ESNET for distributing the article and to El Faro for producing it. ESNET’s introductory paragraph is followed by the El Faro article.

10 months into the ‘state of exception’ which the Government of Nayib Bukele/Nueva Ideas launched in the wake of a weekend of gang murders (in March 2022) the article below from investigative journalists El Faro gives a thoughtful analysis of the massive changes occurring, and the massive price the whole society is paying.

Scenes witnessed in recent weeks by El Faro reporters speak to a new, unknown life for thousands who can cross streets, talk to neighbours, and move on with their lives without gang members subduing them with a gun to their heads. This is, undoubtedly, an extraordinary change.

But it’s worth remembering that gangs weren’t born out of thin air. They were the crudest, most violent expression of a broken, corrupt society, one that gives limited opportunities to most of the population. It is a society marked by poverty, inequality, the impossibility of social mobility, lack of access to fundamental services like health, education, adequate housing, and jobs, and the non-conservation of precarious natural resources.

Those conditions haven’t changed. The current government has no plan for such structural changes capable of shedding the conditions under which these ghoulish expressions started. The fertile soil that allowed gangs to spawn and take root in the underprivileged barrios of most of El Salvador are still there. Repression is not a sustainable solution.

The Bukele regime went from negotiating with organised crime to repressing it only when the pact fell apart. The Army and the Police swept through communities under a state of exception that allowed them to act like prosecutors and judges and arrest without a warrant any citizen they considered a suspect.

Human rights violations have been massive. Thousands of innocents languish in overcrowded prisons. Scores have died in pre-trial detention. Meanwhile, the president boasts of a giant, newly built jail by a handpicked building company that was given a contract with no contest.

We Salvadorans gave up the rights of presumed innocence, legal counsel, fair trial, and to institutions that punish government abuses. We gave up the rule of law that comes with abiding by laws and the Constitution. We gave up freedom of expression, freedom to dissent, separation of powers, transparency in public finances, and mechanisms to fight corruption. We gave up alternation of power. We’re back to corrupt chieftainship.

The visible absence of gang structures, for the first time in a long while, is a fundamental change in the life of thousands of Salvadorans. But the price we’ve had to pay for it is sky-high. The cure could be as harmful as the disease.

What the ‘state of exception’ means in El Salvador

February 2023

The state of exception under which El Salvador’s population now lives was instigated in March 2022 by the country’s President Nayib Bukele. Although the state of exception is a legal mechanism designed to address an emergency situation and is therefore intended to be temporary and extraordinary, Bukele’s continued renewal of the state lends it a permanent and indefinite character under which constitutional rights are restricted. The state of exception was declared as a response to gang violence, but the security forces have committed widespread abuses of human and constitutional rights since the policy’s introduction. These abuses include the detention of many people under the suspicion of gang membership.

The Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad (Exchange and Solidarity Centre), or CIS, is a non-governmental organisation (NGO) which runs a variety of community development programmes throughout the country relating to housing, water provision, sanitation, education and farming. It also runs election monitoring delegations. The organisation’s end of year review includes a description of what the state of exception means to some of the people involved in their development programmes. We include extracts from their report below. We are grateful to Leslie Schuld, director of the CIS in San Salvador, for permission to reproduce their article here.

CIS Review of 2022, December 2022

The current situation: Constitutional rights have been suspended since 27 March 2022 – we are going into our ninth month of the government’s ‘war on gangs’. While people applaud the arrest of gang members, many innocents have been caught in these dragnet operations. Dragnet was a popular TV show in the 1960s about apprehending criminals, but a dragnet is also used for fishing to drag and pick up fish, also snagging anything in its way. Government officials have referred to casting this dragnet knowing many innocents are caught up in it; they say they will let them go if they have no criminal background. Nonetheless, only 800 of over 54,000 arrested to date have been set free, when government sources state that at least 20 per cent have no criminal ties.

The persons set free include those with health conditions, so the government wouldn’t be held responsible for their deaths. A few prisoners have been freed in the middle of the night with no known process or criteria for being let out. And news reports say gang leaders with ties to government officials have also been released.

The CIS continues to focus its efforts to free 22 fishermen from the Holy Spirit Island who have been unjustly arrested, an island with no gangs and no delinquency, and where the CIS has worked since Hurricane Mitch in 1988. This is not a story from the bible, even though of the 22 fishermen, five are named Joseph, two are named Jesus, one is Christian, another is Saviour, among other biblical names.

The CIS was conceded a special hearing on 10th October for the first five fishermen who were arrested from the island. The judge in San Miguel stated that she had no proof of criminal activity, but we had not proven their innocence or ties to the island. We had stacks of sworn statements from community leaders, clients and family members – for the men who had lived on the island for 40 years or were born there. On top of that, over 30 family members travelled from the island to the hearing on 10th October, the very day that Hurricane Julia hit El Salvador. They braved the dangerously rough ocean in small motorboats. They took back roads to the judicial centre as the river had washed out the main route. CIS members and lawyer drove hours from San Salvador and had to wait 30 minutes on two occasions as boulders were cleared out of the road. Everything was suspended that day except the judicial system. Only the lawyer was allowed to be present in the hearing with his stacks of written testimonies, while we waited outside. Four of the five fishermen were present only via a virtual screen. The judge need only to look out of the window at humble family members to know that the men had family ties. Their children were left at home because of the danger that day. The judge focussed on one of the many false accusations – we had not proven that they were not providing food to a gang encampment in the mangroves around the island. CIS has asked: if this encampment exists in the mangroves, why has nobody been arrested there? How big is this encampment, that 22 men must provide food? Since the men work all day fishing, as boat taxis or other labour, who is preparing the food?

The CIS is also offering counselling, food baskets and organisational and legal support to others. Unjust arrests are not the only human rights violations, although they are the gravest since those arrested are automatically given a six month provisional sentence and an added six months after that. Those arrested have not had a visit from a lawyer or family member since the time of their arrest.

We share with you just two examples of other human rights violations faced by the CIS community.

Authorities visited and ransacked one scholarship student’s home four times. CIS provided refuge for fear of her arrest. Afterward, in a fifth visit to her home, the police handcuffed her mother and put her on her knees. She was given three days to turn in a gang member or face her own arrest and the arrest of her daughter (the CIS scholarship student), which they threatened would ruin her career.

Another CIS scholarship home was visited by police at 3 am. The father who suffers from cancer was beaten up. The police took pictures of the family members and their identity documents. A few days later the gangs came to the same home and threatened to kill the daughter (the CIS scholarship student) if the family did not find a house and a title for gang members. CIS counselling and support helped to protect these families.

So, while there is an illusion of safety, projected by millions of dollars spent on publicity saying how safe El Salvador is now, many Salvadorans with scarce economic resources are living in fear. While homicide rates are down, the security, income and well-being of thousands of poor families – who are not involved in criminal activity – are being compromised.

The CIS website: www.cis-elsalvador.org

El Salvador builds Latin America’s largest prison

Key words: El Salvador; state of exception; gangs; prison conditions.

On 3 February 2023, the Salvadoran government opened the largest prison in Latin America. The compound has a capacity for up to 40,000 inmates, is called the Centre for Terrorism Confinement and is located in a rural area 47 miles from San Salvador.

It covers 165 hectares of land and the structure itself covers 23 hectares. The compound has eight electric sub-stations, two water wells, a sewage treatment plant, three miles of access roads and 19 watchtowers with many thermal surveillance cameras. As the cells have toilets and large water basins for washing, inmates will be allowed out only for hearings and to go to the prison infirmary. “No yards have been built, nor recreation area for the inmates, nor conjugal spaces,” Public Works Minister Romero Rodriguez said.

Everyone who enters the facility – including the guards and other staff – must pass through a body scanner to verify that he or she is not carrying a weapon or other contraband. “Normally, telephones, televisions and even prostitutes entered the prisons,” Rodriguez said. “We have tried to guarantee that orders to murder Salvadorans are no longer given from inside the prisons.”

President Nayib Bukele declared a state of excepetion in March 2022 because of the high levels of violence perpetrated by the Salvadoran gangs and since then, his allies in congress have voted every month to renew the state of exception. The state of emergency entails the suspension of constitutional guarantees and allows police to detain people without warrants and in the absence of grounds that would stand up to judicial scrutiny.

Nearly 63,000 people with gang connections have been arrested, according to the government, but families of many detainees say that their loved ones were law-abiding citizens. Many organisations and human rights advocates have described the arrests as a massive human rights violation.

Sources:

- Latin America News Dispatch, 6 February 2023, El Salvador.

- Sara Acosta, 3 February 2023, ‘El Salvador builds largest prison in the Americas’, EFE Online News Editor.

See also other entries into the TVOD website for this month [February 2023]:

- Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad CIS), ‘What the ‘state of exception’ means in El Salvador’.

- El Salvador Solidarity Network (ESNET), ‘El Salvador’s State of Exception’

Estimates of gang membership, Central America (Table)