Although aware of the problem of street children, especially in Latin America, I was unaware of the general hostility felt and expressed towards them and to teams of street educators who try to protect them until one evening in 1995 when I accompanied one such team around the centre of Tegucigalpa. It was only then that I began to appreciate the constant danger experienced by both street children and the workers of organisations such as Casa Alianza and the Quincho Barrilete Association. The experience and the hatred that so many citizens feel towards street children are described more fully in an account of that evening given in ‘The Violence of Development’ website. It is this widespread hatred which excuses the unofficial programme of social cleansing carried out largely by police and death squads.

Later that year I had the displeasure of proof reading the English version of Casa Alianza’s submission to the UN Committee Against Torture, a report on ‘The Torture of Guatemalan Street Children 1990 – 1995’, a thoroughly unpleasant booklet documenting “a PARTIAL list of cases of torture against street children in Guatemala City” [emphasis in original.][1] If proof were needed that the major perpetrators of the torture and killings of street children were to be found amongst the ranks of the police and security forces, this booklet provides it.

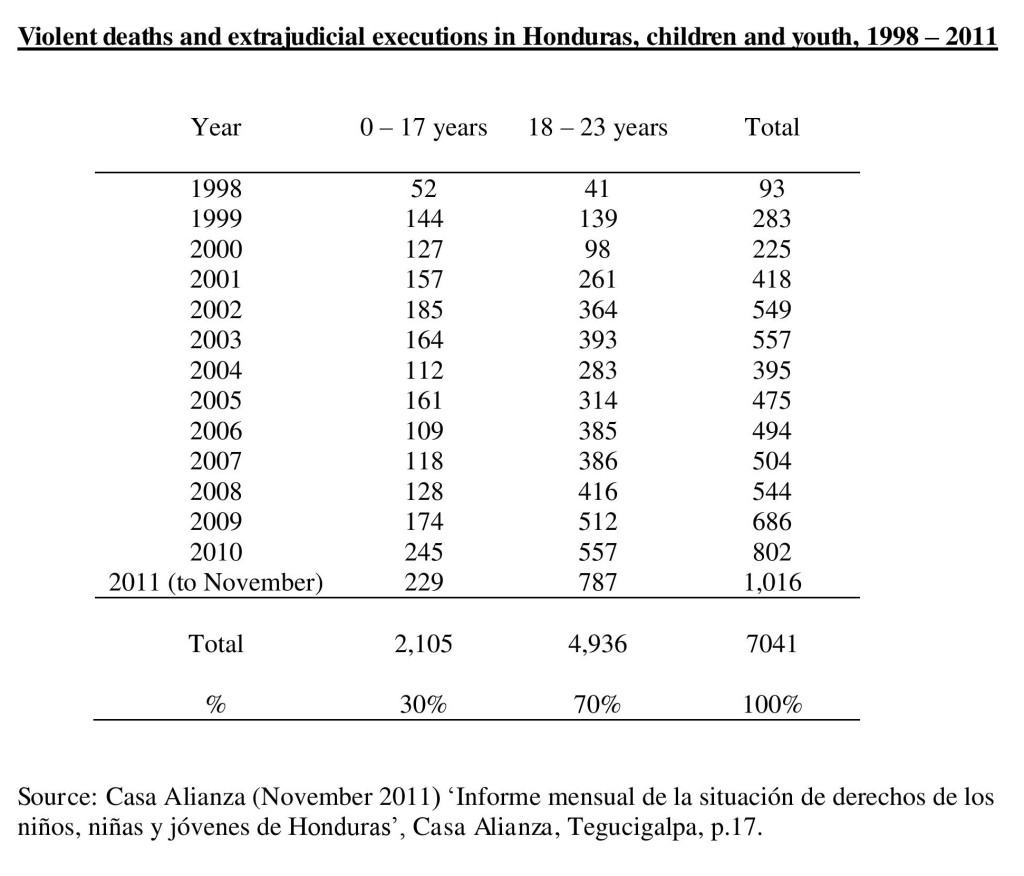

Eighteen years later the number of street children in Central American cities has not decreased and governments have failed to implement solutions that prevent children feeling the need to seek refuge on the streets. Despite some successful and valuable programmes to tackle the problem, it is not possible to report much progress. A total of 373 children and youth under the age of 23 were murdered in Guatemala City during the first six months of 2003. 105 of these (28 per cent) were under 18 and some as young as 12 years. The statistics were collected by the Legal Aid Programme of Casa Alianza Guatemala.[2] In Honduras between 1998 and December 2003, Casa Alianza documented 2,089 extrajudicial murders of children and youth under the age of 23.[3] Figure 9.1 brings the statistics for Honduras up to the year of 2011 and shows a shocking recent increase, suggesting a deliberate strategy of social cleansing – as Duncan Campbell writes, some in Honduras would see it as getting rid of the vermin from the streets.[4]

Founded in Guatemala in 1981, Casa Alianza expanded into Honduras and Mexico in 1986 and Nicaragua in 1998 and serves 4,000 – 5,000 children each year. It describes the situation of most of them as:

abused or rejected by dysfunctional and poverty-stricken families, and further traumatised by the indifference of the societies in which they live. Ubiquitous and growing in numbers, many far too young to comprehend their fate, they beg, steal and sell themselves for a hot meal, a hot shower, a clean bed. Living on the edge of survival, they are often swept in an undertow of beatings, illegal detentions, torture, sexual abuse, rape and murder.[5]

The Quincho Barrilete Association is a NGO which works with abused children in Managua, Nicaragua. There is of course considerable overlap between abused children and street children and María Consuelo Sánchez, director of the organisation, outlines the extent of this overlap for those children helped by the Association, at the same time indicating the nature of the problems they suffer:

76 per cent experience intra-family violence; 31 per cent experience sexual violence; 58 per cent spend much of their time on the street; 18 per cent are at risk of commercial sexual exploitation; 21 per cent have already been victims of commercial sexual exploitation; and 31 per cent work on the streets, selling. Basically, the children who are not at school are on the streets.[6]

Jessica Shepherd reports that Viva, an umbrella organisation for charities that help street children, says that up to 1.5 million Guatemalan children are consistently out of school – that is a fifth of the country’s pupil population.[7] Casa Alianza has also reported several times on threats which have been issued to street educators by patrolling soldiers and policemen. In one extreme case in 2005, lawyer Harold Rafael Pérez Gallardo was murdered in Guatemala City. Harold was a legal programme advisor to Casa Alianza and at the time of his killing was advising the organisation on several pending cases regarding irregular adoptions, murders, sexual exploitations, the trafficking of children and other human rights violations against children.[8]

Like the Casa Alianza observation above, María Consuelo Sánchez also noted the close correlation between family poverty, unemployment and the abuse of children which her organisation attempts to prevent and/or overcome. Behind this link with poverty, at least in part, are the structural adjustment programmes and stabilisation programmes forced on Central American governments by the international financial institutions such as the IMF and supported by various international aid organisations such as the USAID. These ‘agreements’ implemented painful economic reforms which threw thousands of state employees and others out of work and forced the end of food subsidies and school meal programmes, as a result of which, as Dafna Araf noted, “more and more families needed their children to work in order to help the family to survive.”[9]

Such neoliberal economic policies led to more flexible working patterns, or put another way, to the chance for employers and companies to pay their workers less and demand more from them. In such a world, “children make good employees – the cheapest to hire, the easiest to fire and the least likely to protest.”[10] The link between such policies and the increase in the number of street children is indirect, but the link between street children and the violence meted out to them is direct. Many working class and middle class commuters of Tegucigalpa resented the existence and presence of these children and were prepared to turn a blind eye to their removal – by whatever means and with whatever violence necessary.

[1] Casa Alianza / Covenant House (November 1995) ‘Report to the UN Committee Against Torture on the Torture of Guatemalan Street Children’, Guatemala City, p.4.

[2] Casa Alianza (July 2003) ‘Six months of bloodshed in Guatemala City – 373 young victims’, Guatemala.

[3] Casa Alianza (December 2003) ‘Increase of Child Murders in Honduras in November’, Tegucigalpa.

[4] Duncan Campbell (29 May 2003) ‘Murdered with impunity, the street children who live and die like vermin’, London: The Guardian.

[5] Casa Alianza (undated) ‘Giving Children Back Their Childhood’, Covenant House Latin America.

[6] María Consuelo Sánchez (6 July 2009) interviewed specifically for this book by Martin Mowforth, Alice Klein and Karis McLaughlin, Managua, Nicaragua.

[7] Jessica Shepherd (8 March 2011) ‘Street life’, London: Education Guardian, p.1.

[8] Casa Alianza (5 September 2005) ‘Legal Program Advisor from Casa Alianza Murdered’, Guatemala City: Casa Alianza.

[9] Dafna Araf (November 2003) ‘Children of the Street – Troubled Past and Uncertain Future’, San José: Mesoamerica, 22 (11), p.6.

[10] Ibid.