By James Phillips, Covert Action Magazine

June 25, 2025

We are grateful to James Phillips for this article which is available for public use since its publication online by Covert Action Magazine. The original (22nd June 2025), is available at: https://covertactionmagazine.com/2025/06/25/los-horcones-honduras-reflections-on-a-massacre-and-its-legacy/

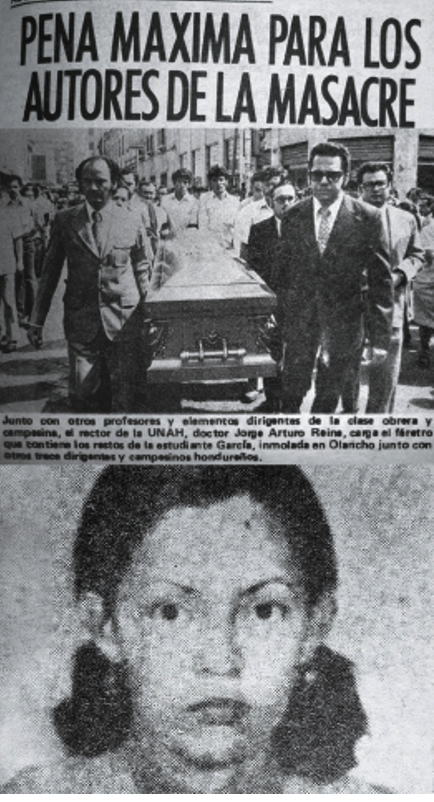

[Source: cac.unah.edu.hn]

[Source: goodreads.com]

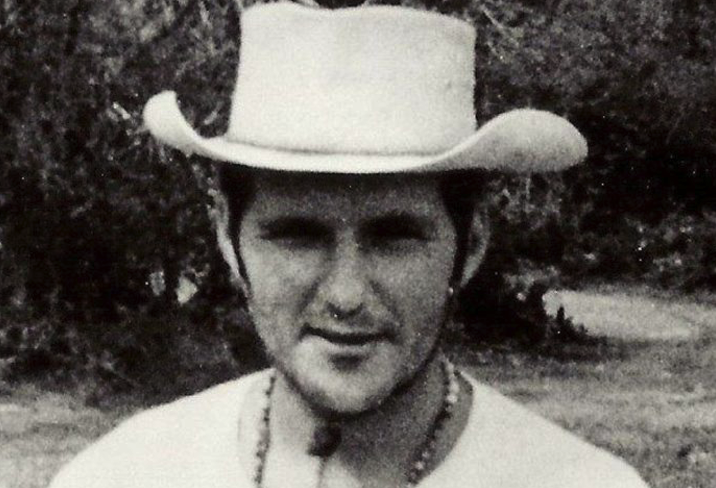

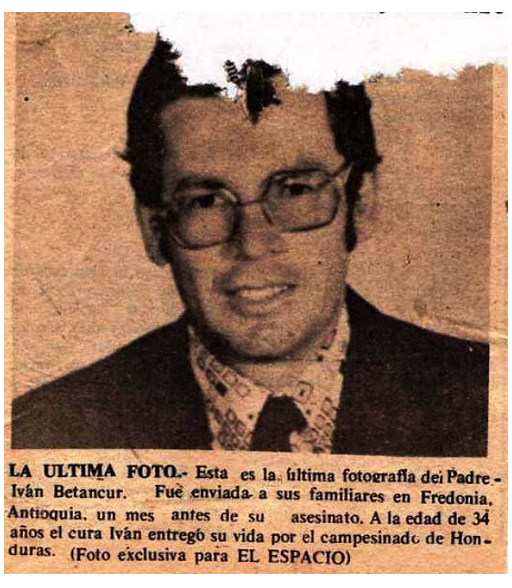

The massacre occurred in the Lepaguare Valley, in the municipal district of Juticalpa, in the Department of Olancho, on the hacienda “Los Horcones,” There, a group of military officers and landowners (or their paid agents) tortured and murdered 15 people, including 11 peasant farmers, two young women, and two Catholic priests—Ivan Betancur (a Colombian citizen) and Casimir Cypher (a U.S. citizen from Wisconsin).

Casimir Cypher [Source: uscatholic.org]

The peasants were leaders and members of the National Peasant Union (Union Nacional de Campesinos, UNC), an organization influenced by the social teachings of the Catholic Church that emphasized social justice, human rights, and a ”preferential option for the poor.” The UNC had organized a “March of Hunger,” to highlight their demands for land that they felt was illegally and unjustly being monopolized by the large ranchers. The large landowners in the region decided to eliminate this threat, and the Honduran military government colluded with them in doing so.

The military blocked the march, but that was only the catalyst for a vicious campaign against the peasants and their Catholic Church supporters. The landowners set a price of $10,000 for the head (literally) of the progressive Catholic Bishop of Juticalpa, Nicholas D’Antonio (a U.S. citizen from New York). They also paid the military commander of the region $2,500 to kill Father Betancourt whom they saw as a supporter and enabler of the peasants. (In current dollars, those sums would be considerably higher.)

It soon became clear that the Honduran military government under General Juan Alberto Melgar Castro was deeply involved. The government responded to the Los Horcones massacre by giving a few military officers jail sentences, but it also raided and destroyed the offices of the UNC, hunted other UNC leaders, and effectively ordered the expulsion from Honduras of all foreign priests.

[Source: honduras2etc.wordpress.com]

General Juan Alberto Melgar Castro [Source: alchetron.com]

As Lernoux documents, the campaign against peasant organizations and progressive elements of the Catholic Church had been going on for months before Los Horcones, with arrests, beatings and imprisonment of priests and peasants in different parts of Honduras.

In 2013, Honduran Jesuit priest and human rights leader Ismael Moreno (Padre Melo) wrote that the Los Horcones massacre was probably the starkest example of government repression against the Catholic Church in recent Honduran history, and that it caused Church leaders and many others to move away from their support of popular demands for social justice. But its significance goes beyond even that.

Ismael Moreno (Padre Melo). [Source: nonosolvidamosdehonduras.blogspot.com]

Such land occupations (tomas de tierra) were and still are a regular event in Honduras where rural communities desperately need land to plant food crops, while large corporations and landowners hold thousands of acres of unused land. A contingent of Honduran soldiers was loitering in the road beside the plot where the peasants were working. The soldiers did nothing to stop them, but they did prevent the corporation’s security guards from forcibly evicting the peasants.

I was aware that this was a very rare scene in Honduran history. The military government, in a very brief liberal moment under General Oswaldo López Arellano, had passed the Agrarian Reform Law of 1974 that embodied the principle (in theory) that all Hondurans had the right to a piece of land. Peasant groups took that seriously as they occupied unused lands. “We are the agrarian reform,” they sometimes said. The contrast between this and the events of 1975 could not have been more stark.

Much of recent Honduran history has been marked by such contrasts. The government of President Carlos Roberto Reina (1994-98) managed to exercise some civilian control over the military and to sign international agreements for the rights of the country’s Indigenous people, only to have these advances ignored in practice and undone in the following decade.

Carlos Roberto Reina [Source: timetoast.com]

General Oswaldo López Arellano [Source: thetimes.com]

[Source: pencanada.ca]

There followed 12 years of right-wing repression and corruption, mostly under President Juan Orlando Hernández, one of the organizers of the 2009 coup. Those years were marked by the increasing power of foreign corporations, drug lords and criminal gangs, and the killing, criminalization and displacement of peasant communities and environmental defenders and their organizations. People began to refer to the country as a narco-dictatorship.

Juan Orlando Hernández [Source: prensalibre.com]

I was in Honduras for that election. Hernández’s National Party operatives tried to bribe peasants by offering them money and other desirable goods if they promised to vote for him. Some later said they accepted the bribe but did not vote for him. Hernández’s hand-picked successor was defeated. (Powerful rulers who underestimate the “simple” rural people are often shocked by the result. Somoza made a similar mistake in Nicaragua in the 1970s.)

Thus, in yet another apparent contrast, Hernández’s party lost to Xiomara Castro, who promised a major reform and an end to corruption. When Hernández lost, the U.S. demanded his extradition to stand trial in New York for drug trafficking. He was convicted, sentenced to 45 years in prison, and remains in a U.S. prison. From staunch ally of the U.S. to convicted criminal, he seems to be yet another “victim” of U.S. imperial expediency.

During these past four years, Xiomara Castro’s government has been a classic example of the difficulties facing reformist efforts in a country largely controlled by a determined and ruthless elite that has the support of the U.S. and powerful U.S. corporate interests. In a previous article (CAM, May 3, 2023), I wrote about the dilemmas facing her government. Beyond these dilemmas, Castro has endured veiled and public warnings from the U.S. Embassy that her reforms might be her undoing.

Xiomara Castro [Source: the-independent.com]

This 50th anniversary year of Los Horcones also happens to be an election year in Honduras. National and local elections are scheduled for November. It is certain that the United States will, as always, be deeply involved in shaping the outcome. Whoever wins the election in November, significant change is unlikely, or it will be slow and costly in coming unless, perhaps, the United States as the major influence in Honduras supports significant change—something that would require change in the U.S. itself.

In a global context, Los Horcones at 50 years is part of a much larger conflict that has deeply shaped the past century, especially in Latin America and parts of Asia and Africa. Anthropologists, rural sociologists, and political economists have written about it. In the 1970s, Sidney Mintz wrote about what he and others called the proletarianization of peasant communities in the colonial Caribbean.

Sidney Mintz [Source: hub.jhu.edu]

Rodolfo Stavenhagen [Source: eluniversal.com]

The global corporate economy uses the land for its own profit while harnessing landless people as a cheap labor pool. Two centuries ago, half the world’s population were rural small farmers, peasants. They were the food suppliers and the foot soldiers (often under duress) of empires.

Today, their numbers are a fraction of what they were. Their land-rooted way of life is considered obsolete in the global commercial economy. Empire today depends on direct control of land and resources and a large, landless and cheap labor pool.

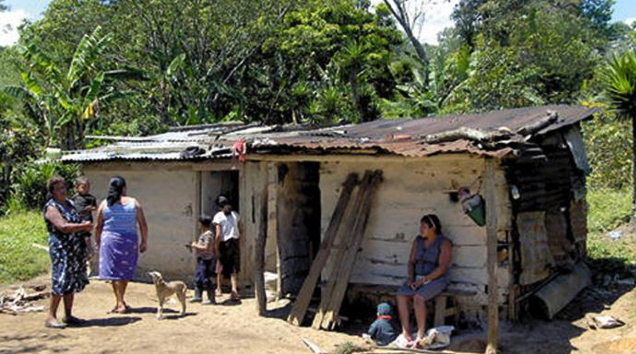

Now and in the near future, even this labor force of recycled peasants is quite likely to become a victim of mechanization and advanced technology, making them entirely superfluous in the plans of global capital—not needed as workers and too poor to be consumers. We already see the result of that in cities filled with displaced peasant families whose children grow up in poverty, vulnerable to gang recruiters and to other threats to body and soul. The cost, in endless conflict and misery, is incalculable.

The landless poor in Honduras: victims of extractive capitalism and the plunder of Central America by foreign corporations. [Source: archivo.tiempo.hn]

It does not have to be this way. There are examples of thriving peasant communities that maintain their way of life, their identity, and their ability to make important decisions while contributing to the food security and economy of their country. Many studies have shown that peasant farmers and cooperatives are often more productive than large plantations. What is required is a government that believes in the worth of peasant communities and is willing to support them while curbing the worst predations of large landowners and corporations. This shift in a country’s political economy and mentality is seldom easy and never perfect.

Many peasant communities are thriving in Honduras, including especially those run as cooperatives. [Source: kairosphotos.com]

Los Horcones is emblematic of the insatiable forces that drive this situation. That is why we must remember horrific events like Los Horcones today. The courage and sacrifice of the peasants and their supporters reminds us of what is at stake.

[Note: In descriptions of the Los Horcones massacre, the three foreign priests are named and, thanks to Lernoux, we know the names of the two young women—Maria Elena Bolivar who would have become Fr. Betancur’s future sister-in-law, and Ruth Garcia, a Honduran university student. I have not found anywhere the names of the eleven peasant members of UNC. There might be a story in that. If anyone knows their names, please share them. They deserve to be remembered by name. JP]