The arrest of Maya K’iche’ journalist Anastasia Mejía exposes the Central American country’s ongoing assault on press freedom. Details of the arrest and its context are told by Iñigo Alexander in a report in the journal of the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA). We are grateful to Iñigo for the story and to NACLA for permission to reproduce the article in The Violence of Development website. The original article by Iñigo Alexander can be accessed at: https://nacla.org/news/2020/11/01/indigenous-journalist-guatemala-press-freedom

Key words: Guatemala; Indigenous journalists; repression; guilt by association; lack of press freedom; self-censorship; SLAPPs.

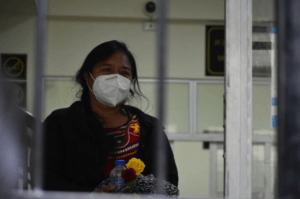

Anastasia Mejía was released from jail to house arrest last week. (Carlos Choc, Prensa Comunitaria)

For 37 days, Maya K’iche’ journalist Anastasia Mejía was held in detention at a women’s prison on the outskirts of Quetzaltenango, a small city in Western Guatemala. The National Police detained Mejía on September 22 and charged her with sedition, aggravated attack, arson, and aggravated robbery. She now faces three months on house arrest, after local organisations raised funds to pay her bail. Mejía is the director of the local outlets Xol Abaj Radio and Xol Abaj TV.

Mejía’s case is symptomatic of the Guatemalan state’s troubled relationship with the press. She is the latest in a series of Indigenous journalists criminalized for their work. Many journalists have been arrested, threatened, and murdered. Public officials openly criticize journalists and consider them “guilty by association” for reporting on protest movements.

A month prior to her arrest, Mejía was working in the town of Joyabaj. The 49-year-old was reporting on protests against the mayor and his management of the Covid-19 crisis. Joyabaj vendors had gathered in opposition to mayor Florencio Carrascosa’s proposed relocation of the town’s market, which has been closed to deter the spread of the coronavirus. Protestors claimed the relocation would not prevent losses and was of no benefit to the businesses that relied on the market.

The mayor had also come under fire for alleged favouritism in the distribution of government support packages to alleviate the impact of the pandemic in the community. Tensions quickly boiled over, and the crowd of protestors raided the Joyabaj town hall, tossing furniture and documents onto the street and setting them ablaze.

All the while, Mejía stood by and reported on the events as they unfolded. Over the course of several hours, she live-streamed the protests on Xol Abaj TV’s Facebook page. This action lead to her unwarranted imprisonment.

Guilty by Association

“What we’ll often see is that rural or Indigenous reporters that are covering protests, confrontations, or conflicts will get lumped in with whatever actions are going on there, and then they’ll be facing ridiculous charges,” says Natalie Southwick, Central and South America Program Coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Southwick says the Guatemalan government’s approach of deeming journalists guilty by association is a gateway to abuse its power and undermine national laws. “Defamation laws are a common way to use the legal system to go after journalists. This is a tactic that is not unique to Guatemala, but it’s used there more than we see in other countries,” says Southwick.

Guatemalan law stipulates that anyone arrested must receive an initial hearing on their case within 24 hours of their arrest. Mejía’s first hearing was on October 8, 16 days after her arrest.

The Joyabaj mayor and Mejía share a fraught history, which many believe is the driving force behind Carrascosa’s persecution of the journalist. In 2015, Mejía was elected as a councilor at the town hall, which Carrascosa has presided over as mayor since 2008. The pair share personal and political differences, with Carrascosa claiming Mejía attempted to oust him, while Mejía went as far as suing Carrascosa over suspicions of corruption.

Carrascosa is reported to have amassed 24 official complaints against him while serving as Joyabaj mayor, including cases of violence against women, illicit funding, embezzlement, and fraud.

The delayed hearing allowed the Joyabaj municipality to prolong Mejía’s time in detention. A series of obstacles emerged in Mejía’s path towards justice, from Covid-19 to missing legal accreditation from Carrascosa’s defense.

Mejía was due to testify via video from the detention centre in Quetzaltenango, though the court was not able to establish connection with the centre and the hearing was postponed until October 28, 36 days after her arrest.

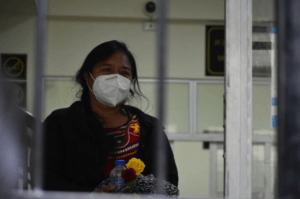

Mejía arriving at the hearing on October 28, 2020. (Carlos Choc/Prensa Comunitaria)

The outcome of Mejía’s hearing echoes the troubled relationship between the Guatemala government, Indigenous communities, and the press.

The court hearing on October 28 upheld the charges against Mejía and ordered an investigation into the journalist. The judge placed Mejía under house arrest and imposed a 20,000 Guatemalan Quetzal ($2,567) bail, as well as denying her the right to practice journalism until the following hearing. The second hearing is scheduled for nearly three months from now, on January 11, 2021.

Additionally, Mejía was forced to spend the night at the men’s prison of Santa Cruz del Quiché, after the state penitentiary’s transport reportedly left her and fellow detainees behind. A day after the hearing, local organisations raised the funds to pay for her bail, and Mejía was released from the detention centre and placed under house arrest for the coming months.

State Attacks on the Press

Since 1992, 25 journalists and media workers have been killed in Guatemala, with the most recent fatality registered in February this year, when Bryan Guerra, a reporter at the cable news channel TLCOM, was shot dead in the city of Chiquimula. In 2019, the humanitarian organisation Unit for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders in Guatemala registered 104 attacks against journalists. So far in 2020, the Association of Guatemalan Journalists has recorded over 110 attacks against members of the press.

“Freedom of speech is not a right exclusive to journalists, it’s a right of the people. If they silence the press, they silence the people,” says Miguel Ángel Albizures, President of the Association of Guatemalan Journalists.

Government disdain toward the press is by no means a new occurrence in Guatemala. The last Guatemalan President, Jimmy Morales, was openly hostile towards the press and often attacked publications and journalists critical of his administration, as well as intimidating journalists and barring them from press conferences.

His successor, Alejandro Giammatei, took office in January this year. Many Guatemalan journalists hoped he would usher in a new age of press freedom. Giammatei, however, has drastically fallen short of the mark, and many Guatemalan journalists believe he holds a tighter grip on the press than Morales did before him.

“People have always had hope [for a freer press], but it crumbles with the start of each new government,” says Albizures. “We’ve been waiting for a change for a long time, and the people were tired of Morales’ attitude towards the press.”

Shortly after winning the election, Giammatei labelled the news outlet Nómada as “specialists in discrediting,” as well as proposing a platform of centralized press releases, which would have enabled the government to filter and manage the flow of information. Nómada has since folded, citing financial instability, though its founder was also facing allegations of sexual misconduct.

Giammatei has also kept a close eye on journalists investigating his administration. In September, journalist Sonny Figueroa was arrested in relation to his reporting on government corruption. Previously, Giammatei had also demanded the investigative journalist Marvin Del Cid reveal who was telling him to investigate his administration.

“Since taking office Giammatei has held a direct attack towards the press, especially those outlets that don’t align themselves with the government’s agenda,” says Nelton Rivera, an investigative journalist at Prensa Comunitaria.

“The government is uncomfortable and annoyed that there is a right that allows citizens to learn, find out, and uncover information, which in turn allows them to make their own decisions,” says Rivera.

The Central American country is ranked 116th on the World Press Freedom Index, reflecting the government’s failure to protect its journalists and provide them with safe, free, and transparent grounds upon which to carry out their labour.

Indigenous Journalists Face Discrimination

Mejía’s Indigenous identity adds a layer of complexity to her case. The journalist is Maya K’iche’, an Indigenous group of 1.7 million in Guatemala, or 11 percent of the national population.

“The State of Guatemala was founded on three pillars which remain practically intact: discrimination, racism and exclusion,” Albizures says. “The fact that she’s Indigenous has a large part to play; it’s an eminently racist attitude which has resulted in her imprisonment.”

Indigenous communities across Guatemala face regular discrimination and independent, Indigenous media outlets are often victims of targeted attacks. Between 2016 and 2018, at least two Indigenous radio stations were raided and shut down due to licensing problems.

Radio holds a particularly important role among Indigenous Guatemalan communities, as it serves to preserve Indigenous languages and culture, and dedicates time to issues impacting their communities. These raids often result in arrests and subsequent criminal charges. In 2018, two female community reporters were arrested following a raid on four Indigenous radio stations.

Indigenous journalists often struggle to obtain the recognition and credibility of mainstream outlets, which in turn reduces the attention and protection they receive from industry peers and state bodies.

In 2016, the Guatemalan state attempted to implement a community media law to provide legal access and protection to broadcast outlets and safeguard Indigenous peoples’ right to produce free journalism. The proposed law was stalled before National Congress could vote on the measure.

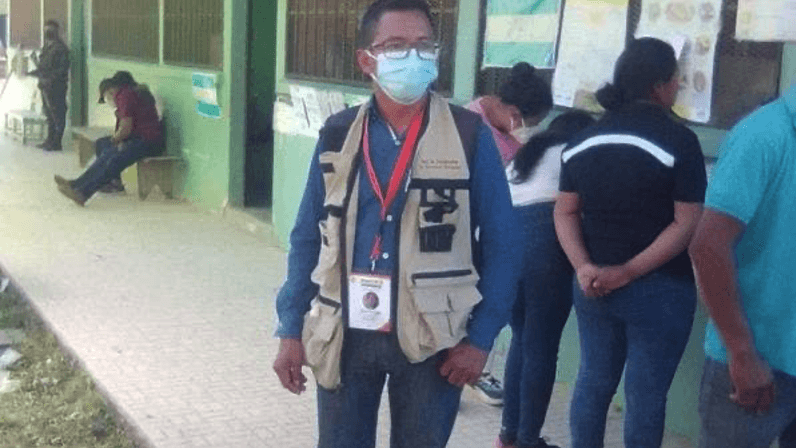

Working within a small community also means that reporters are more exposed and easier to identify. Earlier this April, the Indigenous journalist Carlos Choc had his home robbed and equipment stolen in what is believed to be an attempt at intimidation.

“There are fewer resources in general going to these [Indigenous] regions, and when you have reporters that are actively documenting what’s going on, that puts an additional target on their back,” Southwick says.

As a result, Indigenous and community reporters often resort to self-censorship in order to avoid conflict or attacks, and also refrain from reporting instances of intimidation to avoid attention.

“There’s the perception that people who are reporting for these community outlets are inherently activists, instead of recognising that they’re journalists,” says Southwick. “They’re already facing the regular barriers that any journalists would face, on top of that — as members of communities that face discrimination — their works is often minimized or rejected.”

Mejía’s case is unfortunately unlikely to be the last of its kind in Guatemala. It is the culmination of a systematic based in impunity, intimidation, and discrimination. Even if the Guatemalan state grants Mejía her liberty, she and her colleagues will continue to face an uphill battle in the fight for a free press.

“Mejía’s case exemplifies the impunity of the judges, municipality workers, the mayor himself and public prosecutors, who make accusations they know they have no evidence for[1],” Rivera says. “It’s a way of applying a punishment not only to the person for exercising their role as a journalist, but also to society as a whole.”

Iñigo Alexander is a freelance journalist who focuses on social issues, Spain, and Latin America.

[1] See the article on SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) in this Chapter of The Violence of Development website.

Carlos Mejía Orellana killed

Carlos Mejía Orellana killed

Local volunteer firefighters said a third man, Marvin Tunches, was taken to a hospital in serious condition. The press association said Tunches was a reporter for a local cable channel and requested protection for him.

Local volunteer firefighters said a third man, Marvin Tunches, was taken to a hospital in serious condition. The press association said Tunches was a reporter for a local cable channel and requested protection for him.