In 2018, 2019 and early 2020, before the pandemic hit us all, migration flows and rates from the Northern Triangle of Central America to the United States border with Mexico were the subject of relatively frequent attention in mainstream European newspapers as well as in the mainstream US media. The fact that such reports are now less frequent does not mean that the phenomenon has disappeared. For a short time the migrant caravans that were the principal attraction to the ephemeral interests of the western media waned as the lockdowns spread around the globe. But if anything the new conditions of life under the pandemic became worse for a majority of people and the factors driving the local populations of the Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras) to strike out for ‘new ground’ were as strong as they ever had been. Those driving factors included particularly the violence of life in this region where gang and police violence and the threats thereof made daily life intolerable and where trying to ignore such violence by ‘keeping your head down’ had for many become a poor coping strategy. It should come as no surprise therefore that the previous few weeks and months have produced a crop of reports of new caravans making their way to the US-Mexico border. A major difference now (towards the end of 2021), however, is that large numbers of Haitians and African people are now joining the many Central Americans who form the caravans.

A few of the more recent reports are summarised below by Martin Mowforth for The Violence of Development website.

In October [2021] numerous reports of massive migrant crossings through the Darien jungle of Panama were made, most notably by UNICEF. On 8th October the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that “More than 91,000 migrants have crossed Darien Gap on way to North America this year”.

A UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) press release from 11th October reported on the “highest ever number of migrant children crossing the Darien jungle towards the US” in 2021. “Almost 19,000 migrant children have journeyed through the Darien Gap so far this year, nearly three times more than the number registered over the five previous years combined. More than 1 in 5 migrants crossing the border between Colombia and Panama are children.” Horrifyingly, “Half of them are below the age of five.”

“Each child crossing the Darien Gap on foot is a survivor,” said Jean Gough, UNICEF Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean. “Deep in the jungle, robbery, rape and human trafficking are as dangerous as wild animals, insects and the absolute lack of safe drinking water. Week after week, more children are dying, losing their parents, or getting separated from their relatives while on this perilous journey. It’s appalling that criminal groups are taking advantage of these children when they are at their most vulnerable.”

“Never before have our teams on the ground seen so many young children crossing the Darien Gap – often unaccompanied. Such a fast-growing influx of children heading north from South America should urgently be treated as a serious humanitarian crisis by the entire region, beyond Panama,” Gough said.

In Panama, UNICEF and its partners are providing psychosocial support and health services to migrant children, especially those who have been separated from their parents. Together with the Panama government, the UN organisation is distributing water every day to 1,000 people and hygiene kits to migrant adolescent girls and women at the three migrant reception centres in Bajo Chiquito, Lajas Blancas and San Vicente.

The numbers of migrants headed for the US have been bolstered by Haitians and those from African countries, and caravans from the northern triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras continue to form and move northwards to the Mexico / US border.

https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/2021-records-highest-ever-number-migrant-children-crossing-darien-jungle-towards-us

On 29th October, Telesur headlined ‘Hundreds of Haitian Migrants Reported Passing Through Honduras’.

The increase of migrants present in the country is evident, and the groups of Hondurans fleeing the country have been joined by Haitians and Africans. The migration situation in Honduras has become more complicated in recent days with the passage of hundreds of migrants from Haiti and numerous African countries, who seek to reach US territory, human rights defenders reported.

The teleSUR correspondent in Honduras, Gilda Silvestrucci, indicated that in the bus terminals the increase of migrants is evident, and the groups of Hondurans fleeing the country have been joined by Haitians and Africans.

In an interview, the migrant Claude Pierre acknowledged that the road to the United States (US) is “dangerous.” “One suffers a lot, goes hungry, but (one migrates) to see if one can find a better life,” he said.

Data show that in the last weeks Honduras has received more than 3,000 Haitians, a number that will increase and complicate the situation in the border areas. The Honduran defender of migrants’ rights, Itsmania Platero, said that these 3,000 Haitians “are part of a first contingent that left from Panama and there could be up to 80,000 migrants entering this country.”

Marcela Cruz, representative of the CLAMOR network, explained that the shelters provide attention to the migrants, as well as to the thousands of Honduran returnees to whom the Government does not provide any assistance.

Analysts have pointed out that violence and poverty are the main reasons why young people, women and men decide to make the exodus to the United States.

Gilda Silvestrucci noted that although the calls for caravans have ceased, many leave in small groups to meet in Guatemala or in Mexico, where an international caravan of migrants is heading to Mexico City, in search of a response to their requests for refuge.

Also on 29th October 2021, La Prensa Gráfica reported that on the 10th of that month several bodies of migrants were discovered.

Medardo Tejada Portillo (the father), Jenmy (mother) and son Joshua along with Jenmy’s sister-in-law Francisca Dominguez were the victims. The two assassins are believed to have been ‘coyotes’ who had been hired to take them to the United States. It is believed that the victims had paid almost $10,000 for the journey. They had all been shot.

The victims had planned their journey for three months and the money to pay the ‘coyotes’ had been paid by Jenmy’s mother who lives in the United States.

On 5th November, Telesur reported that a ‘Central American migrant caravan overwhelmed the Mexican National Guard’.

(Published 5 November 2021 by Telesur)

On Thursday, a Central American migrant caravan traveling on foot overwhelmed the Mexican National Guard trying to contain its advance and resumed its march toward Mexico City.

The migrants and guard members clashed on the highway linking the towns of Pijijiapán and Tonalá in Chiapas state, leaving at least two guard members injured and many people arrested.

Upon reaching the highway, federal agents got out of their vehicles with shields in their hands and created a barrier to prevent migrants from moving forward. The anti-riot groups initially managed to intimidate the asylum seekers, who ran away. A short time later, however, the situation changed.

At the scene, some 50 migrants counter-attacked the National Guard with sticks and stones. This strong reaction occurred amid the memory of the death of a Cuban migrant who was shot to death by the National Guard over the weekend. After about 10 minutes, the officers rushed into their vehicles to get away as quickly as possible from the site. The caravan then continued moving down the road.

After the altercation, the caravan, composed of some 4,000 migrants, mostly from Central America and Haiti, departed from Pijijiapán on its trek north toward Tuxtla Gutiérrez City in the Chiapas state.

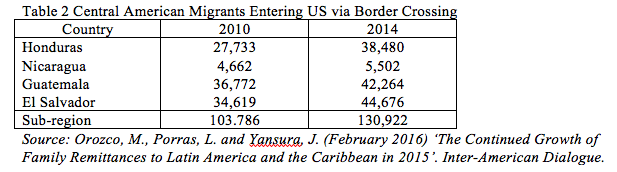

The Central American region is seeing an unprecedented exodus this year. Between January and August, Mexico had reported the entry of more than 147,000 undocumented migrants, tripling the number in 2020, according to figures from the Mexican government.

On 19th November 2021, a new migrant caravan attempted to cross Mexico en route to the Unites States

(By Rubén Morales Iglesias)

A new 2,000 strong migrant caravan, headed to the United States (US), moved out of Tapachula in southern Mexico on Thursday. Tapachula is a city in the state of Chiapas, which borders with Guatemala.

The migrants, Central Americans and Haitians, are attempting to join the first caravan which left Tapachula on October 23 with about 4,000 migrants. That caravan has since whittled down to 700 to 800 according to different reports.

The caravan set out of Tapachula as Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador was in Washington meeting with the US and Canadian leaders talking about migration.

While their objective is to reach the US border, the migrants said they intend to pass through Mexico City where they plan on meeting with López Obrador to ask for humanitarian visas and permanent resident cards in Mexico City to move freely in the country while trying to get to the US.

On 21st November 2021, Mexican authorities found more than 400 migrants in trailers.

(By Aaron Humes: Associated Press)

More than 400 migrants transiting Mexico were found in the back of two trailers, not far from where two separate migrant caravans were located heading north toward the United States.

The group, according to the Veracruz state’s Human Rights Commission’s representative Tonatiuh Hernández Sarmiento, were very dirty, covered in mud, in overcrowded, hot and wet conditions, and included children, pregnant women and ill people. The migrants were held by authorities in a fenced yard until federal immigration agents could retrieve them.

In recent meetings the leaders of Mexico, the United States and Canada discussed immigration, agreeing to increase the paths for legal migration, for example with more visas for temporary workers. They also pledged to expand access to protective status for migrants and to address the causes that lead them to migrate, but did not offer hard numbers or timelines for implementation.

But the clandestine flow of migrants who pay smugglers for direct trips to the US border continues, and those active on the issue say the agreement provides few advances and depends on conditions on the ground, where authorities continue to violate the rights of migrants, deny them access to protection, and allow crimes and human rights abuses to occur with impunity.

The migrant caravan currently in Veracruz is the first to advance so far in the past two years, because since 2019, security forces have stopped and dissolved the caravans. This time, the Mexican government used the offer of humanitarian visas to diminish the caravan’s numbers as it slowly moved north, but some have remained suspicious and continued walking. Some migrants who received the documents have reported being swept up by authorities in the north and returned to Tapachula near the Guatemala border.

At least one migrant told the Associated Press he was prepared to find work in Mexico and enter the US legally when he could – but that he could not risk going back to his home country, in this case Haiti.

Such headlines and reports make it clear that the Central American crisis of violence, economic disadvantage, corruption and population displacement has not disappeared, despite the fact that it now rarely appears in our mainstream media.

On this theme, we recommend our readers to another item in this month’s additions to The Violence of Development website, namely the CounterPunch article by W.T Whitney. In the last few paragraphs Whitney gives some context behind these escalating migration rates.

‘US Intervention and Capitalism Have Created a Monster in Honduras’ by W.T. Whitney in CounterPunch.