By John Perry

Two Worlds blog: (twoworlds.me)

February 19, 2020

The following article by John Perry comes from his Two Worlds blog. It originally appeared in The Grayzone, an independent news website dedicated to original investigative journalism and analysis on politics and empire – thegrayzone.com. I am grateful to John for permission to reproduce his article in this website.

Here’s a headline you won’t see: Nicaragua is at peace. After the violent attempt to overthrow the government in 2018, which cost at least 200 lives, the country has largely returned to the tranquillity it enjoyed before. This is not only the impression that any visitor to Nicaragua will receive, it is confirmed by statistics: Insight Crime analysed homicide levels across Latin America in 2019 and showed that only three countries were safer than Nicaragua in the whole continent. What’s more, three of its neighbours, the ‘northern triangle’ of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, were all among the worst countries. They also have high levels of fatal violence against women. In the first 24 days of 2020, for example, 27 Honduran women met violent deaths, while next-door Nicaragua continues to have one of the lowest levels of femicide in Latin America.

But wait. A headline in January denounces the Tragic Epidemic of Violence in Nicaragua. This month the UN slates the Nicaraguan government for allowing repeated attacks against indigenous peoples. A UN ‘situation report’ talks about a general environment of threat and insecurity. Towards the end of last year the systematic, selective and lethal repression of peasant farmers was reported. Where do these allegations come from and what do they mean?

The latest ones come from an incident at the end of January. Criminals attacked a small community in the large forest reserve of Bosawás. It was reported by Reuters to have led to six deaths, ten people being kidnapped and houses being destroyed. The Guardian, New York Times and Washington Post all repeated the story. Local right-wing newspaper La Prensa quoted the NGO Fundación del Rio who called it a ‘massacre’. Nicaragua’s opposition Civic Alliance joined in by calling it ‘ethnocide’. For the opposition news channel Patriotic Communications it was a ‘war’ against indigenous people in which ‘the Ortega government is silent’ about the crimes committed. Amnesty International condemned ‘the state’s indifference’ to the sufferings of indigenous people. The Interamerican Commission for Human Rights said the government was failing its international obligations.

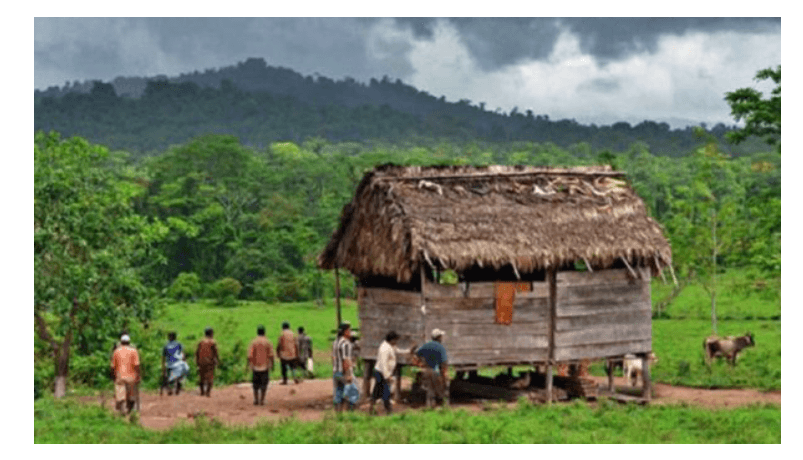

Bosawás is the largest area of tropical rainforest north of the Amazon. It has few roads and mainly tiny communities, many relying on rivers for transport. Many local people belong to indigenous groups which have been granted land titles by the government and this land cannot be sold, only leased. Others are settlers (called ‘colonos’) some of whom have leased land but others who occupy it illegally. Disputes between established farmers and landless peasants are common, and for many years have sometimes resulted in violence. The problems of policing such places, with their history of conflict and corruption, are not confined to their remoteness.

What really happened in the recent case only became clear after the police arrived to investigate, having been called to the scene of two reported deaths, not six, late on the afternoon of 29 January. In the place where the attack occurred, the community of Alal, the police found 12 houses had been burned down and two people had been injured. No one had disappeared. By 31 January they had checked three more nearby communities and found no evidence of murder or kidnapping. Local community leaders condemned the false news reports.

Then, at a completely differently place 12km east of Alal, along the River Kahaska Kukun near the community of Wakuruskasna, police found and identified four bodies, two in one part of the river and two in another part, apparently dead from gunshot wounds. Local people said they knew of no one who had disappeared or was missing. Investigations continued and two days later senior police and government officials met with the community in the local school to explain the investigations and the enforcement work they were doing, as well as the help that people would get to rebuild their destroyed houses. Then, on February 5, the families of the victims met with Nicaragua’s Procurator of Human Rights, Darling Ríos, to denounce the crimes committed. The police are pursuing the criminal gang involved and so far (February 12) have captured one culprit who was carrying a sub-machine gun.

The background to this story is important and is ignored by the international media and human rights bodies. A significant proportion of Nicaraguan territory is legally held by indigenous groups and has been duly titled by the Nicaraguan Government in each community’s ownership. The authorities that administer them are designated by the communities themselves. In the indigenous territory of Mayangna Sauni As, made up of 75 communities, there is an internal dispute over control of these communal lands. Some of the leaders have sold land to groups of outside settlers, which is possibly at the root of last month’s conflict.

Sadly, despite a massive and ongoing process of land reform in Nicaragua, there are still cases of displaced peasant farmers who can’t buy expensive land in populated areas and seek to buy it cheaply, and perhaps illegally, elsewhere, or simply to occupy it. Sparsely populated areas like Bosawás are especially vulnerable. The ensuing conflicts are portrayed by international organisations as struggles between environmentally conscious indigenous people and destructive outsiders, abetted by the government. The reality is that poor people are in competition for land, sometimes violently. And the violence is spasmodic: there were few reported deaths in land disputes for the last two years, although there were several in 2015 and 2016, mainly affecting a different indigenous community, the Miskitu.

It is hardly surprising that news media side with indigenous groups and that the settlers rarely get a voice. Inevitably, as in the Alal case, whoever can get a story out via a phone call will receive attention, and even an agency like Reuters will (it seems) accept such a report before the facts can be checked. To those unfamiliar with Nicaragua, any news item about indigenous groups conjures images of uncontacted tribes in the Amazon, which is far from the real situation. News media set the scene with romantic images of rainforests. Only rarely do they send reporters to investigate in depth.

If this is to be expected of today’s media, it shouldn’t be the case with human rights NGOs. Yet Nicaraguan-based ‘human rights’ bodies are notoriously biased politically, and have long passed the point where they can be considered objective. Their recent allegations of a government campaign of rural assassinations, for example, were shown to be completely false. All the local NGOs compete for donations from foreign governments, and (as one admitted) exaggerate their death counts in order to get it.

Regrettably, the international NGOs are little better. Amnesty International’s reporting on Nicaragua has been shown as full of errors and misrepresentations. Global Witness was earlier called out for biased reporting of the land disputes in the Bosawás area, in which it called Nicaragua the world’s ‘most dangerous country’ to be an environmental defender. Despite many efforts to get it to listen to the complexities of the real story, it refused to withdraw its allegations even when some were found to be completely untrue.

This is why headlines like ‘A Tragic Epidemic of Violence’ should not be taken at face value. Even the BBC (Six indigenous people reportedly killed in attack) was wrong. Media bias against Nicaragua’s Sandinista government is unremitting, and international NGOs are feeding it (as, of course, is the US government). Meanwhile, behind the headlines, Nicaraguan people are successfully recovering the precious peace and safety they enjoyed before the violent events of 2018. Most are relieved that the real ‘epidemic of violence’ ended a few months after it began.

A version of this article appears in: The Grayzone and also in Tortilla con Sal and here in Spanish (en Español).