The following report is produced from news and supplementary material from Jiri Spendlingwimmer, a Costa Rican anthropologist, Liz Richmond, a member of the Environmental Network for Central America (ENCA), and numerous news reports in Costa Rican journals and daily newspapers. We are grateful to Jiri and Liz for their work on this.

December 2020

Key words: IMF loan; national dialogue; blockades; selling of state assets; National Rescue Movement (NRM); international freight movement.

(Photo credit: National Association of Public and Private Employees (Asociación Nacional de Empleados Públicos y Privados, ANEP)

In October 2020, the Costa Rican government led by President Carlos Alvarado began negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) seeking a $1.75 billion dollar loan to overcome the country’s fiscal deficit, projected to reach 9.7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for 2020. The fall in GDP is due to high unemployment – on average 20% for men and 30% for women[1] – and the impact of the coronavirus.

To secure the loan, proposals included an increase in taxes, funding cuts to social programmes, selling of State assets and public institutions, some of which provide important resources for various social programmes.

In response, a National Rescue Movement (NRM) formed and commenced Blockade actions such as demonstrations and roadblocks, rejecting all aspects of the package, arguing that it would be detrimental to the poorest residents of Costa Rica, especially at this time of high unemployment and increasing social tensions. Blockade actions were intended to impact large companies, including those that pay no tax, and were an argument for the collection of unpaid or evaded taxes, which are 6-8% of GDP. The NRM also pressed for a ‘Tobin’ tax on financial conversions between countries.

The roadblocks were effective in preventing the movement of road freight along the Pan American Highway, thereby stalling the provision of goods not just for Costa Rica, but also for the other Central American countries. The agricultural sector reported losses of over $37 million because of the roadblocks with banana and pineapple producers being the worst affected, with losses of $29 million and $7.5 million respectively for transnational companies. Banana Link also reported job losses and other disruptions.[2]

Under pressure not just from within Costa Rica but also from the rest of Central America, President Alvarado withdrew from the initiative and negotiations. The roadblocks continued for a while and became associated with violence according to the Security Minister Michael Soto Rojas, who accused the protest organisers of being infiltrated by narco traffickers and delinquents.[3] The NRM organisers also claimed that organised crime was taking advantage of the situation by instigating violence.[4] Certainly there were acts of violence from which the protest organisers distanced themselves but Soto failed to provide any proof of the accusation.

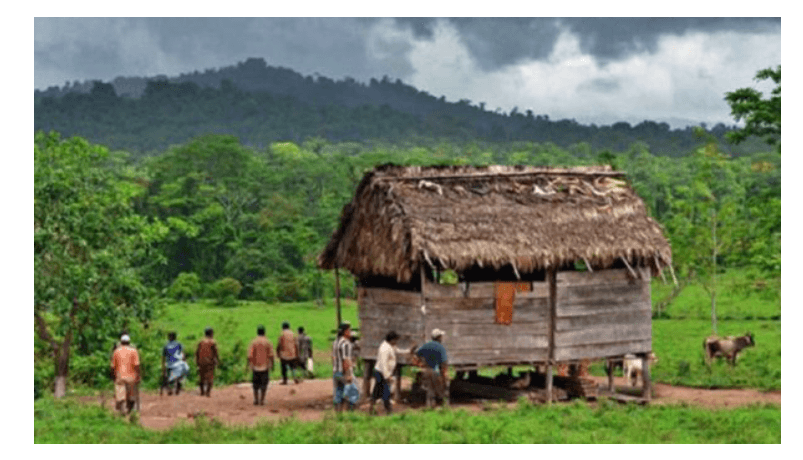

In press reports, the delinquents were usually described as ‘local’. One local chapter of the NRM is the ‘Longo Mai, Tarise and Convento of Buenos Aires Blockade Commission’, situated in Southern Costa Rica. As well as supporting the national agenda, they have a local agenda, which includes a demand for fibre-optics information and education, a request for police support within communities regarding the illegal hunting of wild animals and marijuana crops, drug trafficking and economic support and reactivation for local farmers – campesinos – with strengthening of agricultural production for food sovereignty, not for the transnational companies. They also demand settlement of the historical debt of the government with Indigenous people, and a solution to the current conflict within Indigenous territories, including due processes of investigation and clarification regarding the murders of Indigenous leaders Sergio Rojas and Jehry Rivera, and immediate police action to protect the physical integrity of Indigenous land reclaimers following recent acts of violence in China Kichá,[5]

The ‘Longo Mai, Tarise and Convento Blockade Commission’ action took place 30 September to 15 October 2020, when it was forcibly ended by police intervention, with five people arrested and detained overnight, including two Indigenous residents and a child. They have subsequently initiated a counter legal claim against the state for their illegal detention by the police.

The Blockade took place daily from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., with openings every 3 hours. Free passage was granted to emergency services, elderly, those with medical appointments and other special circumstances. Their petition has not been responded to, and the government’s condition was an end to Blockades prior to any dialogue.

Nationally, the government does not recognise the NRM as a socio-political actor and ordered Blockades to be forcibly lifted on occasions with the use of tear-gas. The government proposal for an IMF loan was withdrawn on 4 October 2020, with dialogues taking place between political, business, trade union and academic sectors to address the fiscal, economic and political crisis of the country.

The ‘Longo Mai, Tarise and Convento Blockade Commission’ continues to organise and participate in meetings with the NRM and will continue in the struggle with local and national proposals against the government’s negotiations with the IMF.

Although the Mintpress news referred to Alvarado’s withdrawal from the negotiations with the IMF as “a victory for the protestors”[6], since the ending of the blockades President Alvarado has said that he will have to enter into negotiations with the IMF again in the new year.

Notes

[1] Continuous Employment Survey carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC): for the second quarter of 2020, unemployment in Costa Rica reached 20% for men and 30% of women nationwide.

[2] https://www.bananalink.org.uk/news/protests-cause-more-than-37-million-loss-for-costa-rican-agriculture-just-2-days/ – 07102020

[3] Loaiza, V. and Chaves, K. (8.10.20) ‘Costa Rica: delincuentes locales y narcos toman mando de protestas y bloqueos’, La Nación, San José.

[4] Annika Beaulieu, 23.10.20, ‘Trouble in Paradise: Violence at protests threaten to unhinge IMF agreement in Costa Rica’, Latin America News Dispatch.

[5] Environmental Network for Central America, November 2020, ‘Land disputes in southern Costa Rica’, ENCA Newsletter 80, p.6.

[6] Alan Macleod (25.10.20) ‘Protests Against Greed and Inequality are Spreading Like Wildfire Through Latin America’, Mintpress News.

Martinelli (pictured) was charged with money laundering in a case known as ‘New Business’ which involved the purchase of public funds. New Business was the name of a front company which collected approximately $43 million from firms that received lucrative government contracts. Those funds were then used to buy a media conglomerate with control of several national papers.

Martinelli (pictured) was charged with money laundering in a case known as ‘New Business’ which involved the purchase of public funds. New Business was the name of a front company which collected approximately $43 million from firms that received lucrative government contracts. Those funds were then used to buy a media conglomerate with control of several national papers.