By Workers World, Editorial, vol 67, no. 1, workers.org/

January 2, 2025

Key words: Donald Trump, History, Panama Canal, US Imperialism

The following is an editorial from Workers World, a US organisation. We are grateful to Workers World for their generalised permission for others to reproduce their articles and editorials verbatim.

Just what is motivating President-elect Donald Trump’s threats to take over the Panama Canal, buy Greenland and make Canada the 51st U.S. state? Does he think he can impose a new historic era of U.S. domination, or is he simply following in the footsteps of his imperialist predecessors — Republicans and Democrats alike?

During his first term, Trump’s “America First” policy was purportedly based on U.S. isolationism. Is his recent demand that the Panama Canal “be returned to us, in full, quickly and without question,” an indication his second term has emboldened him to assert U.S. interests abroad more aggressively? And what motivates his false claim that Chinese soldiers occupy the canal?

Panama’s President José Raúl Mulino’s response to Trump that “every square meter of the Panama Canal and its adjacent area belongs to Panama,” indicates he is taking Trump seriously. And so should we.

In Panama, dozens of protesters gathered outside the U.S. Embassy chanting “Trump, animal, leave the canal alone,” carrying banners reading “Donald Trump, public enemy of Panama.” Saul Mendez, leader of a Panamanian construction union that helped organise the protest, quoted France’s AFP news agency saying: “Panama is a sovereign territory and the canal here is Panamanian. … Donald Trump and his imperial delusion cannot claim even a single centimeter of land in Panama.” (dw.com, Dec. 25)

To dismiss Trump’s demands as frivolous ignores U.S. history and how Washington first came to control the canal.

In 1903, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt financed a revolt to seize territory controlled by the Republic of Colombia in order to create the Republic of Panama. The newly formed “republic” and the U.S. then signed a treaty giving the U.S. control over a 10-mile-wide strip of land to build and operate the canal in exchange for money.

The U.S. ruled the Canal Zone as a settler-colony for more than 60 years, but uprisings by Panamanians in the 1960s and 1970s combined with U.S. military losses in Vietnam led then-President Jimmy Carter to sign a 1977 agreement to return control to Panama.

That legislation, ceding full control over the canal to Panama by 1999, has been unsuccessfully opposed by subsequent U.S. administrations. In December 1989, however, under President George H.W. Bush, the U.S. bombed and invaded Panama and overthrew President Manuel Noriega. Washington claimed this invasion ensured “the integrity of the Panama Canal treaties.”

Competition from planned Nicaragua canal

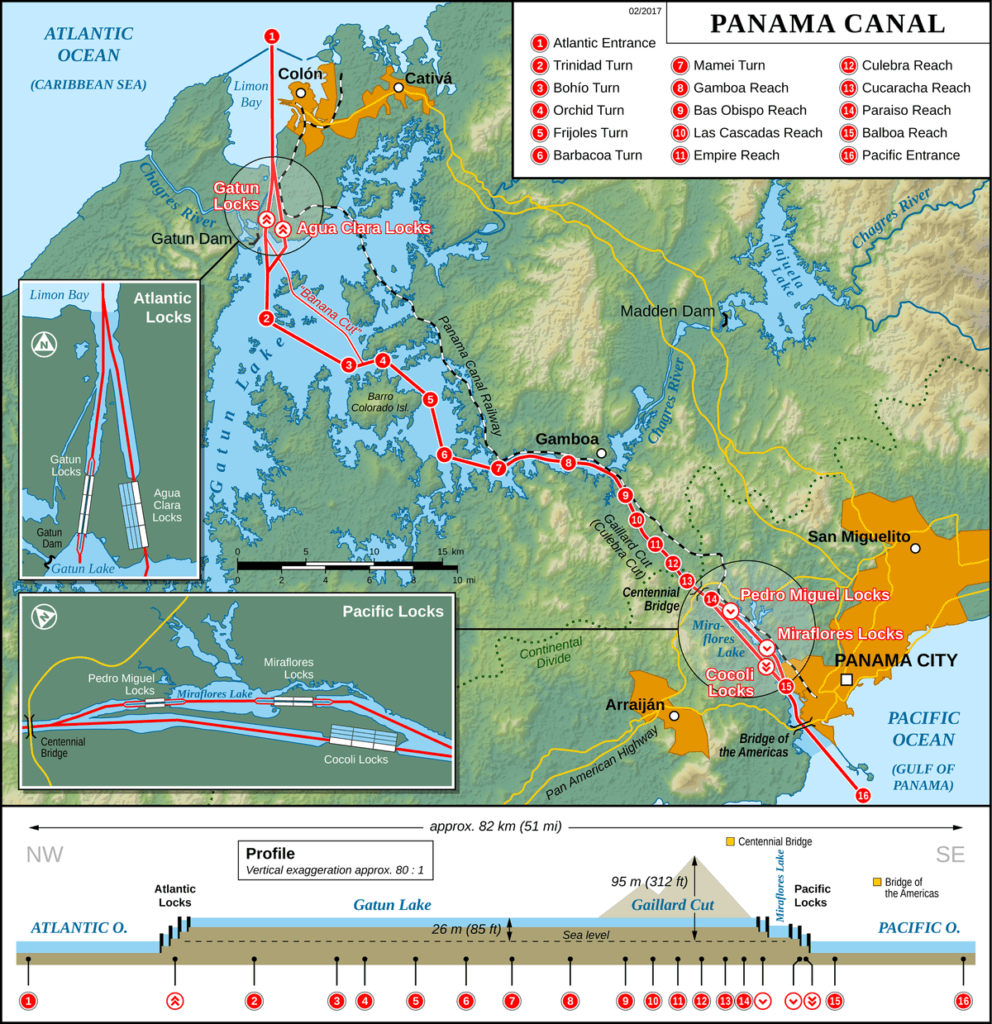

With the canal under Panama’s full control since 2000, a massive project from 2007 to 2017 greatly expanded the canal’s capacity. Recently, however, severe drought around the canal that lowered water levels has hindered its function. These problems led Panama to set restrictions on traffic and impose higher fees.

The number of ships able to use the canal dropped from 14,080 in 2023 to 9,944 in 2024, a drop of 29%, according to the Panama Canal Authority.

The U.S. is the Panama Canal’s number one user. China is number two. In November, China announced that its government has been negotiating with Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega to construct an alternate waterway to connect the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean.

This challenge from China may well be the motivation behind Trump’s threatened takeover and false claims about Chinese soldiers controlling the Panama Canal.

During his first term, Trump repeatedly promoted the idea of the U.S. buying Greenland from Denmark. The Indigenous population of Greenland would clearly challenge any sale. Greenland’s prime minister, Múte Egede, has said, yet again, that the island “is not for sale.”

But Trump hasn’t stopped. While announcing his pick for ambassador to Denmark, Trump arrogantly tweeted: “For purposes of National Security and Freedom throughout the World, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity.” (CNN, Dec. 22)

Trump’s new “America First” pronouncements also included a jab at Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. While threatening to increase tariffs on Canadian imports to the U.S., Trump said it would be a “great idea” for Canada to become the 51st U.S. state.

‘America First’ – same old U.S. imperialism

It may be tempting to dismiss Trump’s comments on social media, but in fact he is following in his predecessor’s footsteps. President Joe Biden laid the groundwork for major U.S. military expansion during his presidency through increased war threats against both Russia and China and total support for Israeli aggression and territorial expansion in West Asia, which includes the recent overthrow of the Bashar al-Assad government in Syria. The field is wide open for Trump.

It is critical for the anti-imperialist movement to understand that Trump makes these threats not as an individual but as the next head of the world’s major capitalist and military power — made all the more dangerous because its economic system is in serious decline.