by T.J. Coles, Counterpunch

20 December 2020

theviolenceofdevelopment.com is grateful to Tim Coles for permission to reproduce his Counterpunch article here. It is a slightly longer article than our website usually includes, but is well worth the read. The original article can be found at: https://www.counterpunch.org/2020/12/20/the-evolution-of-u-s-backed-death-squads-in-honduras/

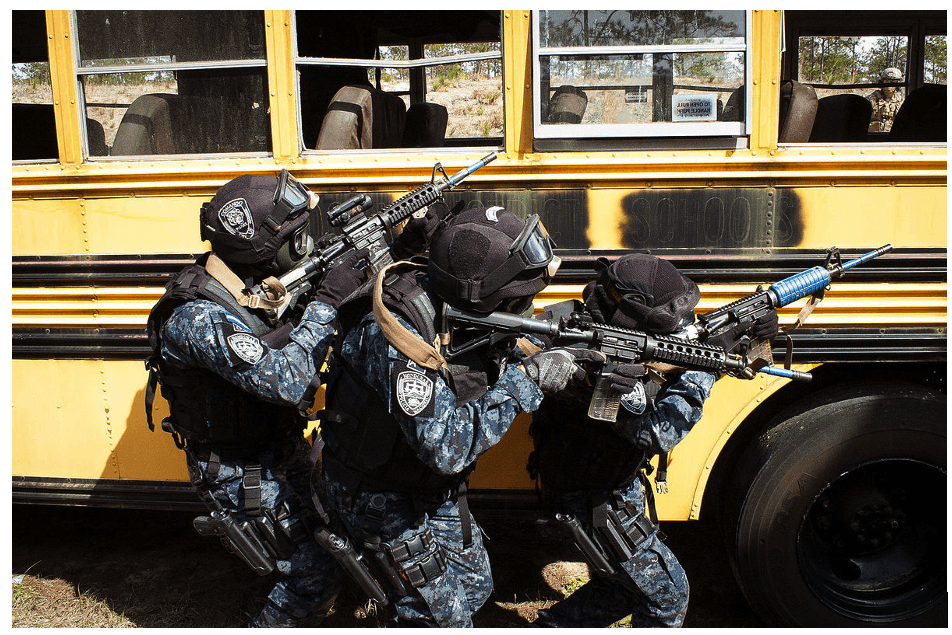

Photo Source Capt. Thomas Cieslak – CC BY 2.0

U.S. intelligence agencies and corporations have pushed back against the so-called Pink Tide, the coming to power of socialistic governments in Central and South America. Examples include: the slow-burning attempt to overthrow Venezuela’s President, Nicolás Maduro; the initially successful soft coup in Bolivia against President Evo Morales; and the constitutional crises that removed Presidents Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil.

In 2009, the Obama administration (2009-17) backed a coup against President Manuel Zelaya. Since then, Honduras has endured a decline in its living standards and democratic institutions. The return of 1980s-style death squads operating against working people in the interests of US corporations has contributed to the refugee-migrant flow to the United States and to the rise of racist politics.

EMPIRES: FROM THE SPANISH TO THE AMERICAN

Honduras (pop. 9.5 million) is surrounded by Guatemala and Belize in the north, El Salvador in the west, and Nicaragua in the south. It has a small western coast on the Pacific Ocean and an extensive coastline on the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic. Nine out of 10 Hondurans are Indo-European (mestizo). GDP is <$25bn and over 60 percent of the people live in poverty: one in five in extreme poverty.

Honduras gained independence from Spain in 1821, before being annexed to the Mexican Empire. Hondurans have endured some 300 rebellions, civil wars, and/or changes of government; more than half of which occurred in the 20th century. Writing in 1998, the Clinton White House acknowledged that Honduras’s “agriculturally based economy came to be dominated by US companies that established vast banana plantations along the north coast.”

The significant US military presence began in the 1930s, with the establishment of an air force and military assistance programme. The Clinton White House also noted that the founder of the National Party, Tiburcio Carías Andino (1876-1969), had “ties to dictators in neighbouring countries and to US banana companies [which] helped him maintain power until 1948.”

The CIA notes that dictator Carías’s repression of Liberals would make those Liberals “turn to conspiracy and [provoke] attempts to foment revolution, which would render them much more susceptible to Communist infiltration and control.” The Agency said that in so-called emerging democracies: “The opportunities for Communist penetration of a repressed and conspiratorial organisation are much greater than in a freely functioning political party.” So, for certain CIA analysts, ‘liberal democracy’ is a buffer against dictatorships that legitimize genuinely left-wing oppositional groups. The CIA cites the case of Guatemala in which “a strong dictatorship prior to 1944 did not prevent Communist activity which led after the dictator’s fall, to the establishment of a pro-Communist government.”

REDS UNDER THE BED

To understand the thinking behind the US-backed death squads, it is worth looking at some partly-declassified CIA material on early-Cold War planning. The paranoia was such that each plantation labourer was potentially a Soviet asset hiding in the fruit field. These subversives could be ready, at any moment, to strike against US companies and the nascent American Empire.

In line with some strategists’ conditional preferences for ‘liberal democracies’, Honduras has the façade of voter choice, with two main parties controlled by the military. After the Second World War, US policy exploited Honduras as a giant military base from which left-wing or suspected ‘communist’ movements in neighbouring countries could be countered. In 1954, for instance, Honduras was used as a base for the CIA’s operation PBSuccess to overthrow Guatemala’s President, Jacobo Árbenz (1913-71).

Writing in 1954, the CIA said that the Liberal Party of Honduras “has the support of the majority of the Honduran voters. Much of its support comes from the lower classes.” The Agency also believed that the banned Communist Party of Honduras planned to infiltrate the Liberals to nudge them further left. But an Agency document notes that “there may be fewer than 100” militant Communists in Honduras and there were “perhaps another 300 sympathizers.”

The document also notes: “The organisation of a Honduran Communist Party has never been conclusively established,” though the CIA thought that the small Revolutionary Democratic Party of Honduras “might have been a front.” The Agency also believed that Communists were behind the Workers’ Coordinating Committee that led strikes of 40,000 labourers against the US-owned United Fruit and Standard Fruit Companies, which the Agency acknowledges “dominate[d] the economy of the region.” In the same breath, the CIA also says that the Communists “lost control of the workers,” post-strike.

A PROXY AGAINST NICARAGUA

A US military report states that “[c]onducting joint exercises with the Honduran military has a long history dating back to 1965.” By 1975, US military helicopters operating in Honduras at Catacamas, a village in the east, assisted “logistical support of counterinsurgency operations,” according to the CIA. These machines aided the Honduran forces in their skirmishes against pro-Castro elements from Nicaragua operating along the Patuca River in the south of Honduras. By the mid-1990s, there were at least 30 helicopters operating in Honduras.

In 1979, the National Sandinista Liberation Front (Sandinistas) came to power in Nicaragua, deposing and later assassinating the US-backed dictator, Anastasio Somoza Debayle (1925-80). For the Reagan administration (1981-89), Honduras was a proxy against the defiant Nicaragua.

The US Army War College wrote at the time: “President Reagan has clearly expressed our national commitment to combating low intensity conflict in developing countries.” It says that “The responsibility now falls upon the Department of State and the Department of Defense to develop plans and doctrine for meeting this requirement.” The same document confirms that the US Army Special Operations Forces (SOF), the 18th Airborne Corps, was sent to Honduras. “Mobile Training Teams (MTT) were dispatched to train Honduran soldiers in small unit tactics, helicopter maintenance and air operations, and to establish the Regional Military Training Center near Trujillo and Puerto Castilla,” both on the eastern coast.

A SOUTHCOM document dates significant US military assistance to Honduras to the 1980s. It notes the effect of public pressure on US policy, highlighting: “a general lack of appetite among the American public to see US forces committed in the wake of the Vietnam War [which] resulted in strict parameters that limited the scope of military involvement in Central America.”

According to SOUTHCOM, the Regional Military Training Centre was designed “to train friendly countries in basic counterinsurgency tactics.” President Reagan wanted to smash the Sandinistas, but “the executive branch’s hands were tied by the 1984 passage of the Boland Amendment [to the Defense Appropriations Act], banning the use of US military aid to be given to the Contras,” the anti-Sandinista forces in Nicaragua. As a result, “the strong and sudden focus instead on training, and arguably by proxy, the establishment of [Joint Task Force-Bravo],” an elite military unit assigned a “counter-communist mission.”

The Green Berets trained the contras from bases in Honduras, “accompanying them on missions into Nicaragua.” The North American Congress on Latin America noted at the time that “Military planes flying out of Honduras are coordinated by a laser navigation system, and contras operating inside Nicaragua are receiving night supply drops from C-130s using the Low Altitude Parachute Extraction System,” first used in Vietnam and operational only to a few personnel. “The CIA, operating out of Air Force bases in the United States, hires pilots for the hazardous sorties at $30,000 per mission.” The report notes that troops from El Salvador “were undergoing US training every day of the year, in Honduras, the United States and the new basic training centre at La Union,” in the north.

SPECIAL UNITS AND ANTI-COMMUNISTS

The US also launched psychological operations against domestic leftism in Honduras. This involved morphing a special police unit into a military intelligence squad guilty of kidnap, torture, and murder: Battalion 316. Inducing a climate of fear in workers, union leaders, intellectuals, and human rights lawyers is a way of ensuring that progressive ideas like good healthcare, free education, and decent living standards don’t take root.

In 1963, the Fuerza de Seguridad Pública (FUSEP, Public Security Force) was set up as a branch of the military. During the early 1980s, FUSEP commanded the National Directorate of Investigations, regular national police units, and National Special Units, “which provided technical support to the arms interdiction programme,” according to the CIA, in which “material from Nicaragua passed through Honduras to guerrillas in El Salvador.” The National Directorate of Investigations ran the secret Honduran Anti-Communist Liberation Army (ELACH, 1980-84), described by the CIA as “a rightist paramilitary organisation which conducted operations against Honduran leftists.”

The CIA repeats allegations that “ELACH’s operations included surveillance, kidnappings, interrogation under duress, and execution of prisoners who were Honduran revolutionaries.” ELACH worked in cooperation with the Special Unit of FUSEP. “The mission of the Unit was essentially … to combat both domestic and regional subversive movements operating in and through Honduras.” The CIA also notes that “this included penetrating various organisations such as the Honduran Communist Party, the Central American Regional Trotskyite Party, and the Popular Revolutionary Forces-Lorenzo Zelaya (FPR-LZ) Marxist terrorist organisation.”

Gustavo Adolfo Álvarez (1937-89), future head of the Honduran Armed Forces, told US President Jimmy Carter’s Honduras Ambassador, Jack Binns, that their forces would use “extra-legal means” to destroy communists. Binns wrote in a confidential cable: “I am deeply concerned at increasing evidence of officially sponsored/sanctioned assassinations of political and criminal targets, which clearly indicate [Government of Honduras] repression has built up a head of steam much faster than we had anticipated.” But US doctrine shifted under President Reagan. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, Thomas O. Enders, told Binns not to send such material to the State Department for fear of leakage. Enders himself said of human rights in Honduras: “the Reagan administration had broader interests.”

Under Reagan, John Negroponte replaced Binns at the US Embassy in the capital Tegucigalpa, from where many CIA agents operated. In 1981, secret briefings informed Negroponte that “[Government of Honduras] security forces have begun to resort to extralegal tactics — disappearances and, apparently, physical eliminations to control a perceived subversive threat.” Rick Chidster, a junior political officer at the US Embassy was ordered by superiors in 1982 to remove references to Honduran military abuses from his annual human rights report prepared for Congress.

THE MAKING OF BATTALION-316

In March 1981, Reagan authorised the expansion of covert operations to “provide all forms of training, equipment, and related assistance to cooperating governments throughout Central America in order to counter foreign-sponsored subversion and terrorism.” Documents obtained by The Baltimore Sun reveal that from 1981, the US provided funds for Argentine counterinsurgency experts to train anti-Communists in Honduras; many of whom had, themselves, been trained by the US in earlier years. At a camp in Lepaterique, in western Honduras, Argentine killers under US supervision trained their Honduran counterparts.

Oscar Álvarez, a former Honduran Special Forces officer and diplomat trained by the US, said: “The Argentines came in first, and they taught how to disappear people.” With training and equipment, such as hidden cameras and phone bugging technology, US agents “made them more efficient.” The US-trained Chief of Staff, Gen. José Bueso Rosa, says: “We were not specialists in intelligence, in gathering information, so the United States offered to help us organise a special unit.” Between 1982 and 1984, the aforementioned Gen. Álvarez headed the Armed Forces. In 1983, Reagan awarded him the Legion of Merit for “encouraging the success of democratic processes in Honduras.” When CIA Station Chief, Donald Winters adopted a child, he asked Álvarez to be the godfather.

After WWII, the US Army established in the Panama Canal Zone a Latin American Training Centre – Ground Division at Fort Amador, later renamed the US Army School of the Americas and moved to Fort Benning, Georgia. Now called the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation, the CIA’s Phoenix Programme in Vietnam and its MK-ULTRA mind-torture programmes influenced the Honduras curriculum at the School.

In 1983, the US military participated in a Strategic Military Seminar with the Honduran Armed Forces, at which it was decided that FUSEP would be transformed from a police force into a military intelligence unit. “The purpose of this change,” says the CIA, “was to improve coordination and improve control.” It also aimed “To make available greater personnel, resources, and to integrate the intel production.” In 1984, the Special Unit was placed under the command of the Military Intelligence Division and renamed the 316th Battalion, at which point “it continued to provide technical support to the arms interdiction programme” in neighbouring countries.

A CIA officer based in the US Embassy is known to have visited the Military Industries jail: one of Battalion 316’s torture chambers in which victims were bound, beaten, electrocuted, raped, and poisoned. Battalion torturer, José Barrera, says: “They always asked to be killed … Torture is worse than death.” Battalion 316 officer, José Valle, explained surveillance methods: “We would follow a person for four to six days. See their daily routes from the moment they leave the house. What kind of transportation they use. The streets they go on.” Men in black ski masks would bundle the victim into a vehicle with dark-tinted windows and no license plates.

Under Lt. Col. Alonso Villeda, the Battalion was disbanded and replaced in 1987 with a Counterintelligence Division of the Honduran Armed Forces. Led by the Chief of Staff for Intelligence (C-2), it absorbed the Battalion’s personnel, units, analysis centres, and functions.

In 1988, Richard Stolz, then US Deputy Director for Operations, told the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in secret hearings that CIA officers ran courses and taught psychological torture. “The course consisted of three weeks of classroom instruction followed by two weeks of practical exercises, which included the questioning of actual prisoners by the students.” Former Ambassador Binns says: “I think it is an example of the pathology of foreign policy.” In response to the allegations, which he denied, former Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs, Elliott Abrams, replied: “A human rights policy is not supposed to make you feel good.”

Between 1982 and 1993, the US taxpayer gave half a billion dollars in military “aid” to Honduras. By 1990, 184 people had “disappeared,” according to President Manuel Zelaya, who in 2008 intimated that he would reopen cases of the disappeared.

THE ZELAYA COUP

After centuries of struggle, Hondurans elected a President who raised living standards through wealth redistribution. Winner of the 2005 Presidential elections, Manuel Zelaya of the Liberal Party’s Movimiento Esperanza Liberal faction increased the minimum wage, provided free education to children, subsidised small farmers, and provided free electricity to the country’s poorest. Zelaya countered media monopoly propaganda by imposing minimum airtime for government broadcasts and allied with America’s regional enemies via the proposed ALBA trading bloc.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) reported at the time that “analysts” reckoned Zelaya’s move “runs the risk of jeopardizing the traditionally close state of relations with the United States.” The CRS also bemoaned Zelaya delaying the accreditation of the US Ambassador, Hugo Llorens, “to show solidarity with Bolivia in its diplomatic spat with the United States in which Bolivia expelled the US Ambassador.”

Because Zeyala did not have enough Congressional representatives to agree to his plan, he attempted to expand democracy by holding a referendum on constitutional changes. Both the lower and Supreme Courts agreed to the opposition parties blocking the referendum. In defiance of the courts, Zelaya ordered the military to help with election logistics, an order refused by the head of the Armed Forces, Gen. Romeo Vásquez, who later claimed that Zelaya had dismissed him, which Zelaya denies. Using pro-Zelaya demonstrations as a pretext for taking to the streets, the military mobilized and, in June 2009, the Supreme Court authorised Zelaya’s capture, after which he was exiled to Costa Rica.

In the book Hard Choices, then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s ghostwriters, with her approval, refer to Latin America as the US’s “backyard” and to Zelaya as “a throwback to the caricature of a Central American strongman, with his white cowboy hat, dark black mustache, and fondness for Hugo Chavez and Fidel Castro” (p. 222). The publishers omitted from the paperback edition Clinton’s role in the coup: “We strategized on a plan to restore order in Honduras” (plus the usual boilerplate about democracy promotion.)

Decree PCM-M-030-2009 ordered the post-coup election be held during a state of emergency. The peaceful, pro-Zelaya groups, La Resistencia and Frente Hondureña de Resistencia Popular, were targeted under Anti-Terror Laws. The right-wing Porfirio Lobo was elected with over 50 percent of the vote in a fake 60 percent turnout (later revised to 49 percent). US President Obama described this as “a restoration of democratic practices and a commitment to reconciliation that gives us great hope.” Hope and change for Honduras came in the form of economic changes benefitting US corporations.”

The US State Department notes: “Many of the approximately 200 US companies that operate in Honduras take advantage of protections available in the Central American and Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement.” Note the inadvertent acknowledgement that ‘free trade’ is actually protection for US corporations. The State Department also notes: “The Honduran government is generally open to foreign investment. Low labour costs, proximity to the US market, and the large Caribbean port of Puerto Cortés make Honduras attractive to investors.”

Four years into Zelaya’s overthrow, unemployment jumped from 35.5 percent to 56.4 percent. In 2014, Honduras signed an agreement with the International Monetary Fund for a $189m loan. The Centre for Economic and Policy Research states: “Honduran authorities agreed to implement fiscal consolidation… including privatizations, pension reforms and public sector layoffs.” The Congressional Research Service states: “President Juan Orlando Hernández of the conservative National Party was inaugurated to a second four-year term in January 2018. He lacks legitimacy among many Hondurans, however, due to allegations that his 2017 reelection was unconstitutional and marred by fraud.”

RETURN OF THE DEATH SQUADS

Since the coup, the US has expanded its military bases in Honduras from 10 to 13. US ‘aid’ funds the Honduran National Police, whose long-time Director, Juan Carlos Bonilla, was trained at the School of the Americas. Atrocities against Hondurans increased under the US favourite, President Hernández, who vowed to “put a soldier on every corner.” SOUTHCOM worked under Obama’s Central America Regional Security Initiative, which supported Operation Morazán: a programme to integrate Honduras’s Armed Forces with its domestic policing units. With SOUTHCOM funding, the 250-person Special Response Security Unit (TIGRES) was established near Lepaterique. The TIGRES are trained by the US Green Berets or 7th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and described by the US Army War College as a “paramilitary police force.”

The cover for setting up a military police force is countering narco- and human-traffickers, but the record shows that left-wing civilians are targeted for death and intimidation. To crush the pro-Zelaya, pro-democracy movements Operation Morazán, according to the US Army War College, included the creation of the Military Police of Public Order (PMOP), whose members must have served at least one year in the Armed Forces. By January 2018, the PMOP consisted of 4,500 personnel in 10 battalions across every region of Honduras, and had murdered at least 21 street protestors.

Berta Cáceres co-founded the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organisations of Honduras. One of the Organisation’s missions was resisting the Desarrollos Energéticos (DESA) corporation’s Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam on the Gualcarque River, which is sacred to the Lenca people. DESA hired a gang, later convicted of murdering Cáceres. They included the US-trained Maj. Mariano Díaz Chávez and Lt. Douglas Geovanny Bustillo, himself head of security at DESA. The company’s director, David Castillo, also a US-trained ex-military intelligence officer, is alleged to have colluded with the killers. The TIGRES forces oversaw the dam’s construction site.

Between 2010 and 2016, as US ‘aid’ and training continued to flow, over 120 environmental activists were murdered by hitmen, gangs, police, and the military for opposing illegal logging and mining. Others have been intimidated. In 2014, for instance, a year after the murder of three Matute people by gangs linked to a mining operation, the children of the indigenous Tolupan leader, Santos Córdoba, were threatened at gunpoint by the US-trained, ex-Army General, Filánder Uclés, and his bodyguards.

Home to the Regional Military Training Centre, Bajo Aguán is a low-lying region in the east, whose farmers have battled land privatization since the early-1990s. After Zelaya was deposed, crimes against the peoples of the region increased. Rights groups signed a letter to then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who facilitated US ‘aid’ to Honduras, stating: “Forty-five people associated with peasant organisations have been killed” between September 2009 and February 2012. A joint military-police project, Operation Xatruch II in 2012, led to the deaths of “nine peasant organisation members, including two principal leaders.” One 17-year-old son of a peasant organiser was kidnapped, tortured, and threatened with being burned alive. Lawfare is also used, with over 160 small farmers in the area subject to frivolous legal proceedings.

“BACK TO THE PAST”

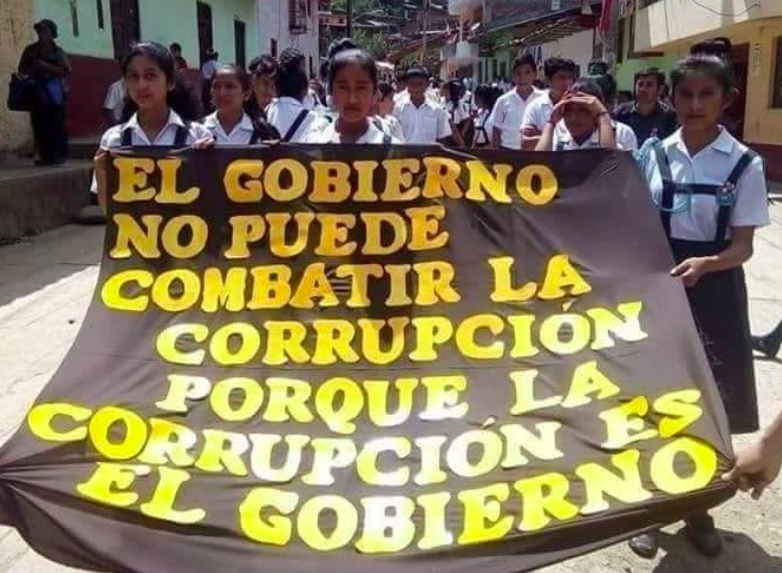

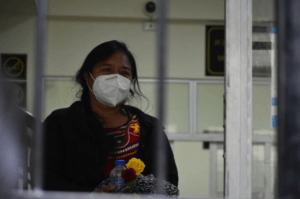

In the 1980s, Tomás Nativí, co-founder of the People’s Revolutionary Union, was “disappeared” by US-backed death squads. Nativí’s wife, Bertha Oliva, founder of the Committee of Relatives of the Disappeared in Honduras to fight for justice for those murdered between 1979 and 1989. She told The Intercept that the recent killings and restructuring of the so-called security state is “like going back to the past.”

The iron-fist of Empire in the service of capitalism never loosens its grip. The names and command structures of US-backed military units in Honduras have changed over the last four decades, but their goal remains the same.

- J. Coles is director of the Plymouth Institute for Peace Research and the author of several books, including Voices for Peace (with Noam Chomsky and others) and Fire and Fury: How the US Isolates North Korea, Encircles China and Risks Nuclear War in Asia (both Clairview Books).

Counterpunch is a non-profit, reader-supported journal that publishes articles and books.

Bertha Oliva de Nativi, mentioned at the end of the article above, appears twice in the interview section of this website. Martin Mowforth interviewed her in 2010 (soon after the coup which ousted Mel Zelaya) and again in 2016 during the rule of organised crime and state violence presided over by Juan Orlando Hernández.