By John Perry

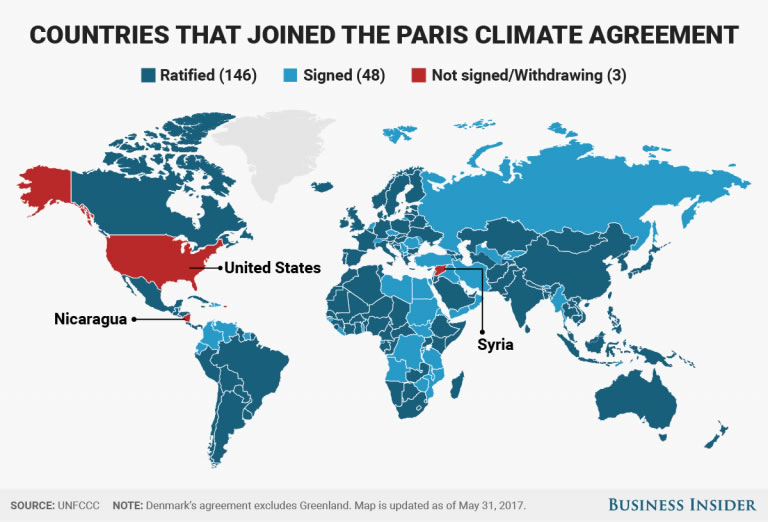

This article was first published in the London Review of Books blog on Oct. 3, 2017 and is reprinted with permission of the author. Nicaragua signed the Paris Agreement on Oct. 23, 2017. (In November 2017, Syria also announced its intention to sign the agreement, leaving only the United States of America as the solitary nation outside the agreement.)

While Donald Trump gives the appearance of wavering over his decision to pull the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement, Nicaragua has decided to sign it. It was one of only two countries not to sign in Paris last year; the other was Syria. Nicaragua abstained out of principle: the agreement didn’t go far enough. The target – to keep the average global temperature no more than 2ºC above pre-industrial levels – was insufficient, and in any case unlikely to be met. An unfair burden was being put on developing nations and not enough money was being promised to help them build low carbon economies. I met Nicaragua’s climate change negotiator, Paul Oquist, in June, a few days after Trump announced his decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. I suggested it would be an excellent moment for Nicaragua to change its mind, though claim no credit for the subsequent decision; I can’t have been the only one to think so.

When Daniel Ortega returned to power in 2007 after 16 years of neoliberal governments, most of Nicaragua’s electricity was produced by burning oil. Shortages led to daily blackouts. Nicaragua was the poorest country in Central America but had the highest electricity prices. Ten years later, blackouts are much less frequent, prices have stabilized and more than half the electricity comes from renewable sources, with a realistic aim of reaching 90 per cent by 2020. Costa Rica has already exceeded that target, but three-quarters is via hydroelectricity, which may be vulnerable as climate change speeds up. Nicaragua’s energy matrix is more balanced, using wind, geothermal, solar and biomass alongside hydro.

Latin America has plentiful renewable sources for electricity generation; the next challenge in reducing emissions will be transport. Even in the bigger cities, public transport is often inadequate and unattractive to the growing numbers who can afford cars. Weaning people off petrol or diesel cars and onto public transport means a major change in mindset for an elite whose point of reference is Miami. In a continent where railways have fallen into disuse and only the poor take buses, infrastructure investment currently means building more roads.

Latin America is a major supplier of ‘ecosystem services’, principally the huge tropical forests that absorb carbon. North of the Amazon, Nicaragua has the biggest area of tropical forest in the hemisphere, but it is under constant threat from settlement, especially for cattle ranching. Ortega has granted a Chinese company the rights to build an inter-oceanic canal, rivalling Panama, on the grounds that it’s the only way to conserve the rainforest. The income from the canal, he argues, combined with the need to guarantee its water sources, will enable Nicaragua to defend the remaining forests and replant the areas now given over to cattle. The canal company, which has yet to start digging, has just announced a big tree-planting scheme.

Nicaragua has suffered several years of limited rainy seasons; the prognosis is for the droughts to get worse. Coffee production and other crops are threatened by rising temperatures. Yet the country generates only 0.03 per cent of global carbon emissions, a paltry 0.8 metric tons per head annually. Costa Rica produces twice that amount per head, the UK eight times and the US twenty times. If developed countries (the US excepted) are serious about the Paris Agreement, they’ll put money into helping poor countries achieve higher living standards without raising emissions. Even the IMF thinks they should do this. But Nicaragua’s skepticism about the likelihood of it happening is more than justified, even if, as an ‘act of solidarity’ with the poorest and most vulnerable nations, it goes ahead and signs.

John Perry lives in Masaya, Nicaragua where he works on UK housing and migration issues and writes about those and other topics covered in his ‘Two Worlds’ blog which can be found at: http://twoworlds.me/ .