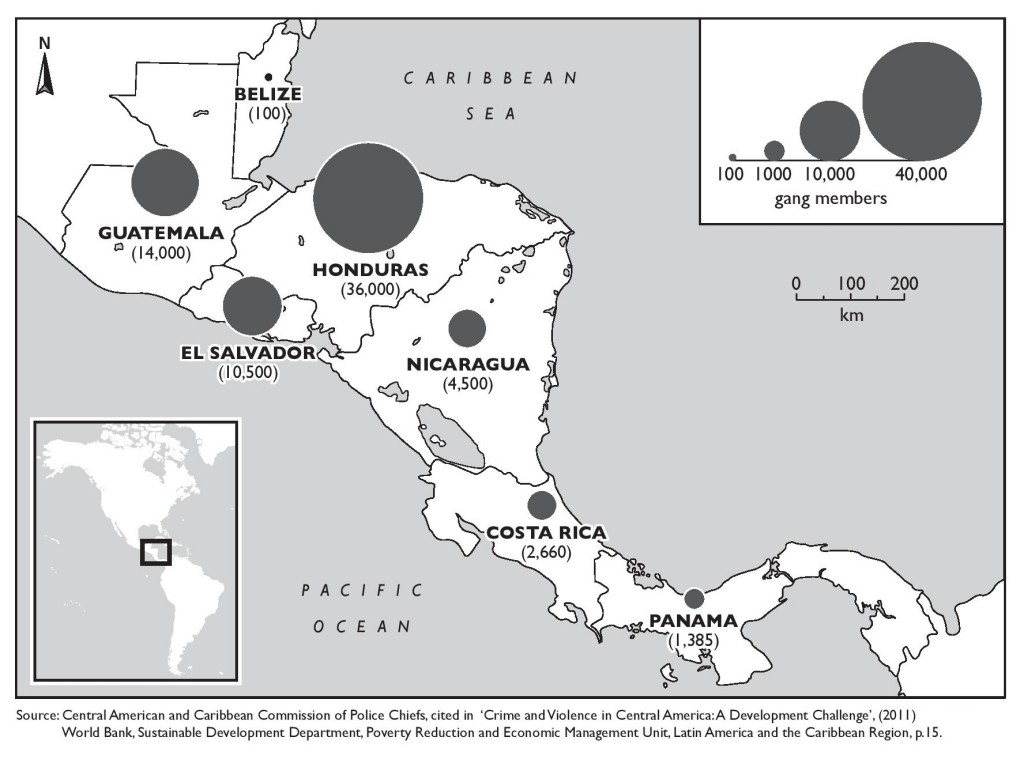

The following map appears as Figure 9.1 in the book (page 189)

Category: Chapter 9

You couldn’t make it up – II – defending the ‘white lobster’

The following text box appears in the book as Box 9.5 (page 193).

In July 2010, the Nicaraguan Navy gave chase to a speed boat that turned out to be carrying 2,756 kilos of cocaine with a street value of US$125 million in the United States.[1] They eventually ran it to ground in Tasbapauni in the Southern Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAS, by its Spanish initials). The occupants of the boat made off inland with the help of local people who, armed with machetes, clubs and in the case of one woman, a broom, threatened to attack the army if they removed the boat and its valuable cargo. This is a situation similar to one that occurred in Walpaisiksa in the Northern Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAN) in December 2009 where two soldiers lost their lives.[2]

On the Caribbean coast, historically neglected by central government and with the highest indices of poverty in the country, for some time people have been living off the profits of the ‘white lobster’, as they call the bales of cocaine washed ashore. They are increasingly turning to drug traffickers for employment and social benefits.

The national press considered it worrying that a woman with a broom was prepared to face the army to protect a consignment of drugs and speculated about what the same woman might do if given a machine gun by the drug smugglers. After a tense stand-off, the army managed to persuade local people to hand over the boat with no bloodshed.

Reproduced with the permission of CODA International and of Gill Holmes from her three monthly Nicaragua Current Affairs Report to CODA International, May – July 2010.

[1] Figures taken from Envío magazine, No. 341, August 2010, p.4.

[2] Gill Holmes, Nicaragua Current Affairs Report for CODA International, November 2009 – January 2010.

Letter from Bismuna – a cracked paradise

This is a shortened version of an article entitled ‘All is not well in Paradise’ which appeared in ENCA Newsletter 34 (August 2003).

By Annette Zacharias and Dieter Dubbert*

Bismuna is an indigenous Miskito village on the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua with a population of about 1,500 people. … The village is on the shore of a lagoon which opens to the sea. In this sea float many kilos of cocaine, packets of 60, 80, 90 kilos of pure cocaine. Why did they come floating our way? Off the Atlantic coast is a group of islands known as the Miskito Cays, hundreds of islands of mangroves which form the ideal hiding place for drugs in transit from Colombia. They are also a good location to re-fuel; but the traffickers have to get rid of their cargo the moment they see a patrol boat.

We have scenes that you would normally associate only with low-grade B-movies: people with dark glasses, bracelets and Rolex watches sitting in boats with two 150 horsepower outboard motors, silent and waiting for their contact with a Kalashnikov by their side. …

In 1993 the first packets were found. Nobody knew anything of drugs, their effects, their potential harm, nor of their value. But almost immediately people heard of astronomical values for them and began to look for more. … we found it difficult to explain how dangerous drugs were. How could they have experience of drug addiction if they’d never suffered it before? And fast money talked more powerfully.

In 1994 we wrote to the governor of our department, Stedman Fagoth, and asked him to address this problem. We suggested that all the cocaine found by the people should be bought officially by the state at market prices and channelled into the pharmaceutical industry. The reply from the governor was … silence. Worse than that, Dieter received a death threat (from an unknown origin). Later we realised that the governor had indeed concerned himself in the business. …

One consequence of the fast money was that people stopped working on their fincas. Nobody wanted to sweat by sowing rice, yucca or plantains. And who’s going to criticise them for preferring to buy everything rather than sweat on their fincas? … Whole families, including even grandmas, lived on the beach looking for the ‘blessing’ of a packet. They sold the drugs, and today there is a well-established system of trafficking. But the worst problem for the community is that many people have taken to using the drugs. We could say that the generation of youths aged 14 – 23 are lost in the drug. But also adult males with their family responsibilities have fallen into addiction.

There is open trafficking, almost risk-free, that transfers many kilos beyond the community and brings back a derivative of cocaine known as ‘crack’ – or ‘stone’ as it is commonly called – a mix of cocaine with ash and soda. According to those already addicted, you only need one stone to become addicted. As a consequence, robberies and violence have arrived in the community. Women fear for their safety. Properties are no longer secure. At night we listen to the rantings of drunks who have left their women. Many people, mainly women, arrive at our house asking for money to buy food or medicines for their children. These children grow up with disastrous, drug-addicted role models, their fathers, brothers, cousins.

Throughout the whole Atlantic coast there isn’t one rehabilitation centre, and the word ‘therapy’ is unknown. The police struggle against the tide with ridiculous budgets incapable of meeting their needs. It’s a public secret that many of the police are involved in this lucrative business, and so its control never progresses. Above all, there is no political interest in protecting the coast and its population.

This situation is dramatic and desperate. But there are a few individuals who are fighting against this appalling form of development.

* Annette Zacharias and Dieter Dubbert lived in Bismuna from 1990 to 2003. They founded a NGO called ‘From Coast to Coast – Solidarity with the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua’ with bases in Kiel, Germany, and Bismuna, Nicaragua. Using donations from Germany, Italy and Nicaragua, it aimed to support the indigenous community through a range of social projects including the construction of a clinic, a sewing workshop, a cultural centre, a baseball stadium and houses for those in need. They also established a rehabilitation centre for youths with drug and/or family abandonment problems. In 2003 they changed location to Waspam in order to increase their work with street children.

Chapter 9: The Violence of Development

This chapter concerns itself with the causes and effects of the wave of violence that for the last two decades have been affecting those sectors of Central American society that have devoted their efforts and energy to defending local and national environments, local communities and policies aimed at benefiting a majority rather than an elite.

It is important to begin with an outline of the origins of the current crisis of violence in Central American societies, and it is important to acknowledge at the outset that these origins lie at least in part with the monopoly of power held by an elite in the Central American region. As the Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad (CIS, Centre for Exchange and Solidarity) in El Salvador explains:

There is a clear transition of power happening in Latin America. There has been a widespread rejection of the elite’s monopoly of power, which was inherited from Spanish Colonialism and was unconditionally backed by the United States governments for the past century. This rejection has resulted in the replacement of military dictatorships with democratic processes over the past two decades. Given that the economic elite largely maintained political power at the beginning of the transition from military dictatorship to democracy, the elite thought their monopoly was invincible and that their economic domination and privileges would be enough to maintain a monopoly on political power.[i]

Other origins of the violence in Central America, however, are also relatively easy to identify, as the following illustrates. As early as 1935, the real role of the US military was noted by some of those within the US armed forces. In a piece entitled ‘War is a Racket’, Major General Smedley Butler declared:

I spent 33 years … in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico … safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902 – 1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested.[ii]

This chapter covers a range of aspects of violence in the region. In some cases, the material here could not be included in Chapter 9 of the book. In other cases, some items which have been included in the book are also included here, but in an expanded form.

Keywords: Human rights abuses | Authoritarianism | Drug trafficking | Oligarchies | Impunity | Death squads | US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) | Social cleansing | Femicide | Coup in Honduras | Gangs / ‘maras’ | ‘Plan mano dura’ | Prison fires | International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG)

[i] Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad (2009) ‘CIS condemns military coup in Honduras’, San Salvador: CIS, 29 June 2009.

[ii] Major General Smedley Darlington Butler (1935) ‘War is a Racket’, available at: www.ratical.com/ratville/CAH/warisaracket.html (accessed 18.03.10).

Honduras most dangerous country for environmental activists

BOGOTA (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Honduras is the deadliest place for environmental activists with scores of Hondurans killed defending land rights and the environment from mining, dam projects and logging, a campaign group said on Monday.

Between 2010 and 2014, 101 activists were murdered in Honduras, the highest rate per capita of any country surveyed in a report by Global Witness, although the overall number was greatest in Brazil.

Globally, killings of environmental activists reached an average of more than two per week in 2014, up 20 percent from the previous year, the report said.

A man looks for usable items in a dumpsite on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa, April 17, 2015. | Reuters/Jorge Cabrera.

Latin America fared worst, accounting for nearly three quarters of the murders – with 29 deaths reported in Brazil, 25 in Colombia and 12 in Honduras.

“Historically there has been very unequal land distribution in Latin America which has caused conflict between local and foreign companies and communities,” Billy Kyte, campaigner at Global Witness, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“Governments in Latin America are by no means taking this problem seriously. Impunity levels are also very high so perpetrators of crime get away with it,” he said.

The report found 40 percent of environmental defenders killed last year were indigenous people caught on the frontline as they tried to defend land and water sources from companies in an escalating scramble for natural resources and land.

“Many indigenous groups lack clear land titles to their land and suffer land grabs by powerful business interests,” the report said.

Honduran activist, Martin Fernandez, said he was forced to flee for safety to Brazil for three months in 2012 after he received telephone death threats and was followed by cars with black tinted windows near his work and home.

“We live in fear, in fear of constant attack. I and many colleagues have had to live in exile,” Fernandez, head of the Movement for Dignity and Justice, a Honduran land rights group, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a telephone interview.

He said Honduran and foreign companies were exploiting indigenous lands and clearing forests, particularly in the northern Yoro province where the Tolupan indigenous group live, to make way for dam construction and mining projects.

In its report, Global Witness said the Honduran government hoped to attract $4 billion in mining investments and recently freed up 250,000 hectares of land for new mining projects.

With the world’s highest murder rate, Honduras is struggling to contain drug-fuelled gang violence and organized crime. The government did not respond to requests for comment on the Global Witness report.

Heightened dangers faced by environmental activists in Honduras are likely to be raised next month at the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council when the country’s rights record comes under review.

(Reporting By Anastasia Moloney; Editing by Rosalind Russell)

On the criminalization and repression of social protest

Amongst the seven Central American countries, Costa Rica has an international reputation for social progress, environmental harmony and sustainability that outstrips the other six countries. In fact Costa Rica has been named by the Happy Planet Index report as the most sustainably happy country in the world.[i] In our experience, Costa Rica deserves many plaudits and is full of really interesting examples of harmony and sustainability; but it is not without its problems and conflicts. We have included here a short opinion piece written in the Costa Rican weekly newspaper Semanario Universidad to illustrate that not all Ticos share this happy perspective.

By Luis Morice (UCR) Sep 20, 2016

Reproduced by kind permission of Luis Morice

From Semanario Universidad, Costa Rica, 21 September 2016

In our country there is no army but there is a machinery of repression that operates in defence of the interests of the major capitalists, in defence of monopolies and of the transnational corporations. They repress people who they say they are defending and they follow the orders of the supposedly ‘progressive’ PAC [Citizen Action Party] government, aiming to intimidate and silence all types of protest and movements of popular discontent. The vilification of social protest becomes ever more frequent through the intensification of the current government’s repressive policies as a bewildering continuation of previous administrations, as well as through various ‘communication’ media which focus and intensify their campaign against it, seeking to demonise mass actions such as the protests and strikes of diverse social movements.

What they are unable to stop by any existing political means, they seek to prevent by means of violence against the people in the street, intimidating the movement of masses of people, intent on delivering the authoritarian message that sees the right to protest as a ‘sin’. This strikes fear into the masses and the working people and instils in them a deep and fierce hatred against this right, undermining the unity of social forces and silencing their denunciations, the discontent, the protest against the rotten and the degenerate. These anti-popular measures and reactions seek to impose a ‘progressive’ government of ‘change’ in holy alliance with global financial entities and with them the national bourgeoisie.

It is shameful to consider as a great example of ‘heroism’ and as a great achievement of the repressive apparatus of the government blue shirts, the ‘re-establishment of order’, or, in other words, the disintegration through violence of whatever struggle the social movement is undertaking. Examples include what happened to the taxi drivers in their struggle against Uber; what happened at the beginning of the year with the displaced families from Finca Chánguena who were protesting against their removal but were brutally repressed by the police force; the same that happened recently with the animalist demonstrators who were protesting for the closure of the Simón Bolívar prison (the zoo for those who consider it as such); or as happened years ago on 8th November when demonstrators from diverse political and social movements took action in defence of the CCSS [Social Security Office] and who were later beaten by police agents. By violence and by nothing more than violence, they stripped them of and fenced them off from their legitimate right to express by means of mass action their rejection and discontent against unjust situations. Faced with this ‘progressive’ government’s repression and with the PAC’s filibustering, [we need] unity and a permanent struggle of the workers.

[i] The Happy Planet Index report, published by the New Economics Foundation, seeks to move away from purely economic measures of happiness and instead ranks countries by how much happiness they get from the amount of environmental resources used. Happiness is calculated by measuring a country’s happiness in relation to the wellbeing, life expectancy and social inequality and then dividing it by its ecological footprint.

Sobre la criminalización y represión de la protesta social

De los siete países de América Central, Costa Rica disfruta una reputación internacional para el progreso social, armonía ambiental y sostenibilidad mucho en delante de los otros seis países. De hecho, se nombra Costa Rica por el Index del Planeta Felíz como el país lo más sosteniblemente felíz en el mundo.[i]De nuestra experiencia, Costa Rica merece muchos aplausos y es lleno de ejemplos de armonía y sostenibilidad muy interesantes; pero no es un país sin problemas y conflictos. Aquí hemos incluido un artículo de opinión corto escrito en el periódico costarricense Semanario Universidad para ilustrar el hecho que no todos los Ticos comparten esta felíz perspectiva.

By Luis Morice (Estudiante UCR) Sep 20, 2016

Producido aquí con autorización de Luis Morice

En nuestro país, no existe ejército pero sí una máquina represora en defensa de los intereses de los grandes capitalistas, en defensa de los monopolios y grandes transnacionales. Reprimen al pueblo que dicen “defender” y cumplen al dedillo las órdenes del gobierno dizque “progresista” del PAC, con el fin de amedrentar y silenciar todo tipo de manifestación y movimiento de descontento popular. Es cada vez más frecuente el envilecimiento de la protesta social producto de la intensificación de la política represiva del actual gobierno como una perpleja continuación de las anteriores gestiones, además de algunos medios de “comunicación” que agudizan e intensifican su campaña en contra de esta, que busca satanizar la acción de masas, entre ellas las protestas y las huelgas de diversos movimientos sociales.

Lo que no pueden detener por ningún medio político existente lo buscan hacer a través del ejercicio de la violencia contra el pueblo en la calle, amedrentando el movimiento de masas, intentando dejar un mensaje casi que de una manera autoritaria haciendo ver el derecho a la protesta como un “pecado” para atemorizar a las masas y al pueblo trabajador e infundir dentro de ellas un odio tan profundo y tenaz en contra de esta, en búsqueda de la inevitabilidad para la realización de dicha acción de masas, para evitar la unidad de las fuerzas sociales y silenciar su denuncia, su descontento, su protesta contra lo podrido y lo degenerado que se desprende de las medidas antipopulares y reaccionarias que busca imponer el gobierno “progresista” del “cambio” en santa alianza con los entes financieros mundiales y junto a ellos la burguesía nacional.

Es una legítima vergüenza considerar como un ejemplo formidable de “heroísmo” y un gran logro del aparato represivo del gobierno, o sea los vestidos de azul, el “restablecimiento del orden” o, en otras palabras, la desintegración por medio de la violencia de cualquier movimiento social en lucha; por ejemplo, lo sucedido con los taxistas en su lucha contra Uber, lo sucedido a principios de año con las familias desalojadas de finca Chánguena que protestaban contra una medida de desalojo pero fueron brutalmente reprimidas por la fuerza policial, al igual como sucedió recientemente con los manifestantes animalistas que desarrollaban su protesta por el cierre definitivo de la cárcel (zoológico para quienes así lo consideran) Simón Bolívar o como ocurrió años atrás un 8 de noviembre cuando manifestantes de diversos movimientos políticos y sociales se movilizaron en defensa de la CCSS y que posteriormente fueron garroteados por los efectivos policiales. Por la violencia y nada más que por la violencia les despojaron, les cercenaron su legítimo derecho de expresar mediante los mecanismos de acción de masas su repudio y descontento contra situaciones de injusticia. Ante la represión del gobierno “progresista” y filibustero del PAC, unidad y lucha permanente de la clase obrera y trabajadora.

[i] El informe del Index del Planeta Felíz, publicado por la Fundación de Nuevo Economía, busca evitar las medidas puramente económicas de alegría y reemplazarlas por un rango de países según la felicidad derivado de la cantidad de recursos ambientales utilizado. La felicidad se calcula por medir el bienestar, la esperanza de la vida y la desigualdad social de un país y dividirlo por su huella ecológico.

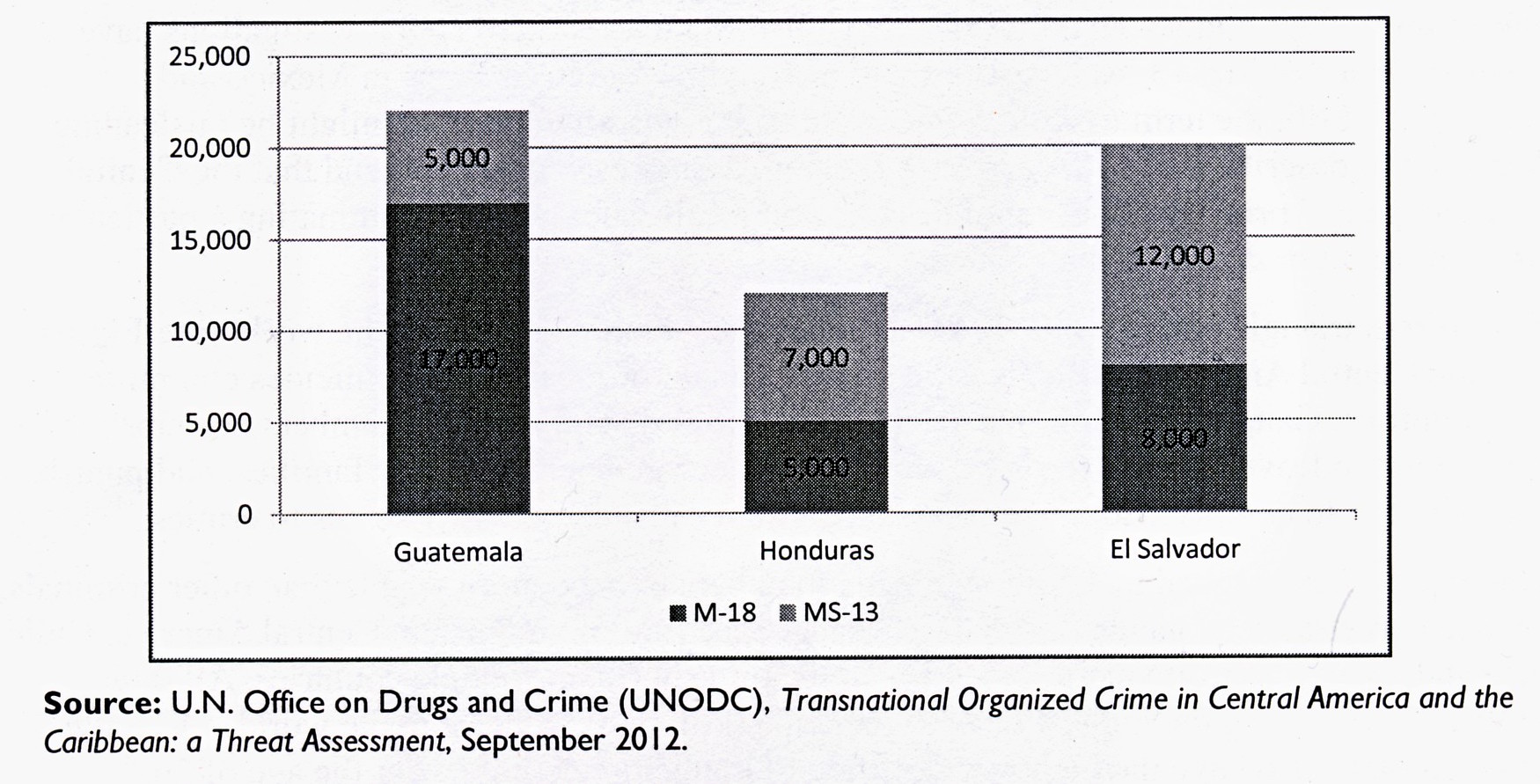

Estimated Gang Membership in the Northern Triangle of Central America, 2012

2016 assassinations of environmental rights defenders in Guatemala

Context

2016 has witnessed an increase in fatal attacks on human rights defenders in Guatemala. From January 1st to October 31st, eleven human rights defenders were killed and since October 31st, the killings have escalated, and by November 18th the total number of defenders killed came to 16. (The total for 2015 was 13.)

Environmental defenders

| On 16th March, Walter Méndez Barrios (shown left) was shot and killed outside his home in Las Cruces. He was a well-known environmental rights defender, who tried to protect natural resources in communities in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. He was a founding member of the FPCR (Petenero Front Against Dams), formed in 2005 to defend land rights, water rights and other natural resources. |

| On 13th April, Benedicto de Jesús Gutiérrez Rosa, Juan Mateo Pop Cholom (shown left) and Héctor Joel Saquil Choc, all forestry engineers with the National Institute of Forests, were ambushed and shot to death by gunmen in a car around 2 pm as they were driving in Carcha, Alta Verapaz. They were returning home from a finca where they had been working for the day. |

| On 8th June, human rights defender Daniel Choc Pop (shown left) was killed by unknown individuals who shot him numerous times. He was an indigenous and campesino human rights defender from the community of San Juan Tres Ríos in Cobán, which he represented at the General Assembly of the Highlands Campesino Committee (CCDA). The CCDA is a national organisation committed to defending local water sources used by indigenous communities. There had been recent disputes over land ownership with owners of the Rancho Alegre estate |

| On 12th November, Jeremy Abraham Barrios (shown left) was shot to death. He worked as the Assistant to the General Director of CALAS (Centre for Environmental and Social Legal Action in Guatemala). CALAS is a human rights organisation based in Guatemala City and has been active in denouncing abuses committed by mining companies as well as in the protection of environmental rights. There was no prior indication that he had received any threats, although the organisation had received warnings. |

Sources:

A variety of sources have been used in the compilation of the lists above. These include: Prensa Libre, Aquitodito, Cerigua, Radio La Franja, Front Line Defenders, Committee to Protect Journalists, NISGUA, UNESCO, Reporteros Sin Fronteras, Guatemala Human Rights Commission/USA (GHRC).

The GHRC’s ‘Preliminary 2016 Human Rights Review’ has been particularly helpful and this was the work of Imogene Caird and Pat Davis, to whom I am especially grateful. The GHRC’s website is: www.ghrc-usa.org/

2016 assassinations of journalist rights defenders in Guatemala

Context

2016 has witnessed an increase in fatal attacks on human rights defenders in Guatemala. From January 1st to October 31st, eleven human rights defenders were killed and since October 31st, the killings have escalated, and by November 18th the total number of defenders killed came to 16. (The total for 2015 was 13.)

Journalists

| On 17th March, Mario Roberto Salazar Barahona (shown left), director of Radio Estéreo Azúcar, was killed in Asunción Mita (department of Jutiapa), as he waited in his car for change after buying a coconut at the roadside. Gunmen pulled up beside him on a motorcycle and opened fire. |

| On 8th April, Winston Leonardo Túnchez Cano (shown left), a broadcaster on Radio La Jefa, was shot and killed by men on a motorcycle while he was shopping for groceries in Escuintla. |

| On 30th April, journalist Diego Salomón Esteban Gaspar (shown left, 22 years old and a leading reporter on Radio Sembrador, was killed by three men who intercepted him on his motorcycle in the village of Efrata (department of Quiché). The director of the radio station had been receiving threats since 2015. |

| On 7th June, journalist Víctor Hugo Valdéz Cardona (shown left) was shot and killed in the streets of Chiquimula by two individuals on a motorcycle. Víctor was the director of Chiquimula de Visión, a cultural television programme that had been showing for more than 27 years. |

| On 25th June, journalist and radio reporter Álvaro Alfredo Aceituno López (shown left) was shot by unidentified assailants on the street where the Radio Ilusión station is located in the city of Coatepeque. He was director of the station and the host of a programme titled ‘Coatepeque Happenings’. |

| A month after Álvaro’s murder, his daughter, Lindaura Aceituno, was shot and killed by men on a motorcycle as she was driving her daughter to school. After the first shooting, one of the men got off the motorcycle and approached and shot her again to ensure she was dead. |

| On 6th November, journalist Hamilton Hernández and his wife, Ermelinda González Lucas (shown left), were assassinated in Coatepeque while returning home after covering an event. Hamilton was a journalist for the cable station, Punto Rojo. The two had been married for only a few months. |

Sources:

A variety of sources have been used in the compilation of the lists above. These include: Prensa Libre, Aquitodito, Cerigua, Radio La Franja, Front Line Defenders, Committee to Protect Journalists, NISGUA, UNESCO, Reporteros Sin Fronteras, Guatemala Human Rights Commission/USA (GHRC).

The GHRC’s ‘Preliminary 2016 Human Rights Review’ has been particularly helpful and this was the work of Imogene Caird and Pat Davis, to whom I am especially grateful. The GHRC’s website is: www.ghrc-usa.org/

2016 assassinations of union and community rights defenders in Guatemala

Context

2016 has witnessed an increase in fatal attacks on human rights defenders in Guatemala. From January 1st to October 31st, eleven human rights defenders were killed and since October 31st, the killings have escalated, and by November 18th the total number of defenders killed came to 16. (The total for 2015 was 13.)

Union members and community leaders

On 10th May, community leader Blanca Estela Asturias was shot to death in Villalobos, Guatemala. Two men approached her as she was at her newspaper stand at 6 am and shot her at point blank range. She had recently organised a protest to call for better water service and better maintenance of the community’s drainage system.

On 19th June at about 6 pm, Brenda Marleni Estrada Tambito (shown left) was driving through Zone 1 of Guatemala City when a vehicle drove up next to her. The occupants of the vehicle opened fire and killed her. She was a member of the Coalition of Workers’ Unions of Guatemala (UNSITRAGUA) and the sub-coordinator of the Legal Aid Commission within the union. UNSITRAGUA brings together workers’ unions from different industries, as well as self-employed workers and independent farmers. She was the daughter of lawyer Jorge Estrada, who is currently involved in investigating and assessing labour rights in several banana plantations in Izabal.

On 19th June at about 6 pm, Brenda Marleni Estrada Tambito (shown left) was driving through Zone 1 of Guatemala City when a vehicle drove up next to her. The occupants of the vehicle opened fire and killed her. She was a member of the Coalition of Workers’ Unions of Guatemala (UNSITRAGUA) and the sub-coordinator of the Legal Aid Commission within the union. UNSITRAGUA brings together workers’ unions from different industries, as well as self-employed workers and independent farmers. She was the daughter of lawyer Jorge Estrada, who is currently involved in investigating and assessing labour rights in several banana plantations in Izabal.

On 10th November, Eliseo Villatoro Cardona was riding home on his motorcycle when two pursuers, also on motorcycles, shot and wounded him. Despite his wounds, he tried to flee, but the gunmen continued to chase him and killed him. Villatoro Cardona was a member of the executive committee of the Organised Municipal Employees’ Union of Tiquisate (SEMOT) in Escuintla.

Sources:

A variety of sources have been used in the compilation of the lists above. These include: Prensa Libre, Aquitodito, Cerigua, Radio La Franja, Front Line Defenders, Committee to Protect Journalists, NISGUA, UNESCO, Reporteros Sin Fronteras, Guatemala Human Rights Commission/USA (GHRC).

The GHRC’s ‘Preliminary 2016 Human Rights Review’ has been particularly helpful and this was the work of Imogene Caird and Pat Davis, to whom I am especially grateful. The GHRC’s website is: www.ghrc-usa.org/

MS-13 seeks truce with the government

Reproduced from LatinoLife

January 2017

This Latino Week

by: Jim McKenna

El Salvador gang requests government dialogue

One of El Salvador’s most prominent maras, MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha), offered to dissolve itself as an organisation in return for government concessions. MS-13 stated that it wanted a dialogue on a range of matters, including political representation and amnesty. The government rejected the proposal, saying that it amounted to negotiations with criminals.

Attempts to control the gangs of Central America is not a new development; with a 2012 truce in El Salvador failing within a year of its implementation. The main difference between 2012 and now was thought to be the promise of dissolution in exchange for government promises, which was previously not offered.

Central American gangs have historically been a problem, with U.S. deportation in the 1980s creating a situation where youth gangs would run rampant in society. Although the perceived importance of such gangs has declined in recent years, Central American cities still remain hotspots for violence, with an estimated 10 homicides a day in El Salvador this year.