For: Proceso Digital Especial (proceso.hn)

28th February 2025

This website has already included numerous articles and reports about illegal logging within the Honduran department of Olancho and the violence that this activity caused for many people there, but especially for the Movimiento Ambiental de Olancho (MAO, Olancho Environmental Movement) and its leader Padre Andrés Tamayo. In February this year, the Honduran online newssheet Proceso Digital, spurred by the most recent and distressing homicide figures for the department of Olancho, produced an alarming summary of violence within the department over the previous ten years.

We are grateful to Jorja Oliver for her translation of the report. The original Spanish version is also included in the website.

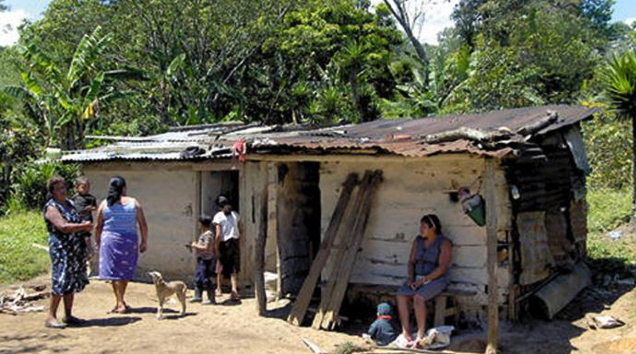

Tegucigalpa- Things aren’t going well for the Olanchanos; the maelstrom of violence marked the biggest department of Honduras since the first day of 2025, with the first femicide of the year; an instance that occurred in Catacamas, the bastion of the presidential family, the Zelaya Castro:

– In 2024, there wasn’t a single Olanchano municipality that didn’t register any homicides.

– The official figures register 965 violent deaths in the Olancho department in the 3 years and 54 days of the administration of President Xiomara Castro.

– The mayor of Catacamas: “we are already used to picking up bodies, taking them to the morgue and delivering them to their families”.

Angie Nicolle Rivera Galeano, a young mother of barely 20 years old, lost her life at the hands of the person whom she thought she’d spend the rest of her life with, her partner. The man attacked her during the night close to the municipal market and fled the scene of the crime with her baby.

The young woman became the first violent death to be registered in Olancho in 2025, generating repudiation from the Catacamenses. But this is not the only municipality where blood has been spilt by the Olanchanos. By the 23rd of February, there were 37 registered homicides in Olancho, only surpassed by the 42 registered in the department of Francisco Morazán, although the population of the latter is bigger.

These figures remain lower than those registered in 2024, when on the same date, according to the public registers of the national police published through the Police Online Statistical System (SEPOL), 38 people died of violent causes, just one more than this year.

In 2025, four of the twenty most violent municipalities in the country are in Olancho: Catacamas, 14 deaths, the third most violent municipality in Honduras, superseded by Tegucigalpa DC with 36, and San Pedro Sula with 18, according to data from SEPOL. The Olancho departmental capital, Juticalpa, is in ninth place, with 7 deaths this year; number 15 is occupied by the municipality of Dulce Nombre De Culmi, with 5 deaths: Guata, in north Olancho, where this year has been the scene of 4 deaths, is in 18th place. The violence in the municipality of Catacamas has motivated the Argentine newspaper INFOBAE to dedicate a report titled “what’s going on in Catacamas? The new kilometre zero for narcotics trafficking and death in Honduras.”

A decade of blood

In 2024, Olancho reported 264 violent deaths, the most violent municipality being Catacamas, with 74 homicides, followed by Juticalpa with 64 deaths, Patuca 19. Culmí 17 and San Esteban 12.

Last year, there wasn’t a single Olanchano municipality that didn’t register any homicides, according to Sepol.

In 2013, the figures showed 54 homicides. Ten years ago in 2015, there were 39. In the 3 years and 54 days (to 23rd February 2025) of the LIBRE party’s administration, the cradle of the presidential couple, things aren’t going well for the Olanchanos, who have cried for the 965 dead.

2022, the first year of Xiomara Castro’s governance was the deadliest in Olancho in the last 11 years and 54 days – SEPOL registered 355 violent deaths that year. In comparison to the first 3 years and 54 days of the administration of the first period of Juan Orlando Hernandez, the Olanchanos cried for 644 loved ones, that is to say 321 people less than the administration of Xiomara Castro, in the same period.

In the meantime, in the second term of Hernandez, the number of violent deaths in the first three years and 2 months, was 860. When comparing the three terms, the footprint of blood that this violence has left in Olancho is 2,469 people.

If this sum is from 2014 to the 23rd February, the date in which SEPOL provided up-to-date data, the trail of violent deaths in Olancho rounds up to 3 thousand, specifically 2,946. In recounting this blood it is important to remember that Olancho is the cradle of three of the last four former presidents of Honduras, if we take into account that the current, Xiomara Castro and former president Porffirio Lobo, have resided the larger part of their lives in the vast department. and Manuel Zelaya was born there.

Violent February

The chain of attacks that occurred on the 14th and 15th of February, that left at least seven dead and at least a dozen throughout Honduras, brought to the mind of the Catacamenses the time of the peak of drug trafficking, in 2007 and 2013, when the planes circulated daily, the massacres had become daily events and the crossfire didn’t respect time or place.

On the night of the 14th of February, a gunman entered a bar and started shooting, killing 4 people n there. This modus operandi was repeated in three other canteens and a barbers, all in less than 24 hours.

After the incident on the Day of Love and Friendship, the mayor Marco Ramiro Lobo said that in Catacamas “we are already accustomed to just picking up bodies, taking them to the morgue and delivering them to their families.” The police deployment continues in the city after the recent incidents, where five attacks occurring in less than 24 hours scared the population; locking them in their houses and leaving the streets totally deserted.

“On that weekend going out frightened everyone, including to the corner shop, these shootings happened in plain sight, close to the church, to the shopping centre, just like confrontations happened in a full market or petrol stations some 15 or 20 years ago,” remembered an Olanchan woman.

The woman remembered that in 2009 a plane landed in a football field in San Pedro de Catacamas, a rural area around 15 kilometres from El Carbon, where the presidential family has their residence

.

Generalised violence in the department

The liberal deputy Samuel García García said that the violence that shakes the municipality of Catacamas also exists in the whole area of Olancho and pointed out that it is linked to the movement of drugs. “There’s lots of crime; people turn up dead in any place, on paths, on roads, machine-gunned in a bullet-riddled car. What is going on is lamentable, the violence is growing more each day in the department”, he said, stressing that the police effort has remained limited. García said that in Olancho there had never been a wave of crime this strong in less than 24 hours, and “really the origin of all these situations, we all know that Olancho has become a place for drug trafficking, as well as organised crime”.

Deaths yes, drug decommissioning no

Despite the fact that, as deputy García points out, “whatever it says in the vox populi, what we are hearing are territorial fights, associated with drugs.” According to Proceso Digital in 2024, a record year for the decommissioning of drugs, no strong operations happened in Olancho.

The minister of security, Gustavo Sánchez, loyal defender of the state of exception which he judges to have led to the decommissioning of some 15 thousand firearms and the confiscation of more than 26 tonnes of cocaine. The official data confirms that 2024 was a record year for the confiscation of cocaine, such that even in the times when the most prolific drug cartels flourished, no more than 25 tonnes of cocaine had ever been confiscated.

In 2012, the country became the most violent in the world with a rate of 86 homicides per every 100 thousand inhabitants. According to the National Observatory of Violence from January to December of 2012, only the department of Olancho exceeded this rate, reaching a rate of 92.5 pccmh[i] with 491 homicides.

Although the figures of current homicides differ from those registered in the strongest time of drug trafficking in the department that inspired the works of the poet Froylán Turcios, with 37 deaths this year, more than 950 in what is the administration of Xiomara Castro and close to three thousand in the last decade, the truth is that things aren’t going well for the Olanchanos.

[i] Pccmh – personas por cada cien mil habitantes; persons for every 100,000 inhabitants.